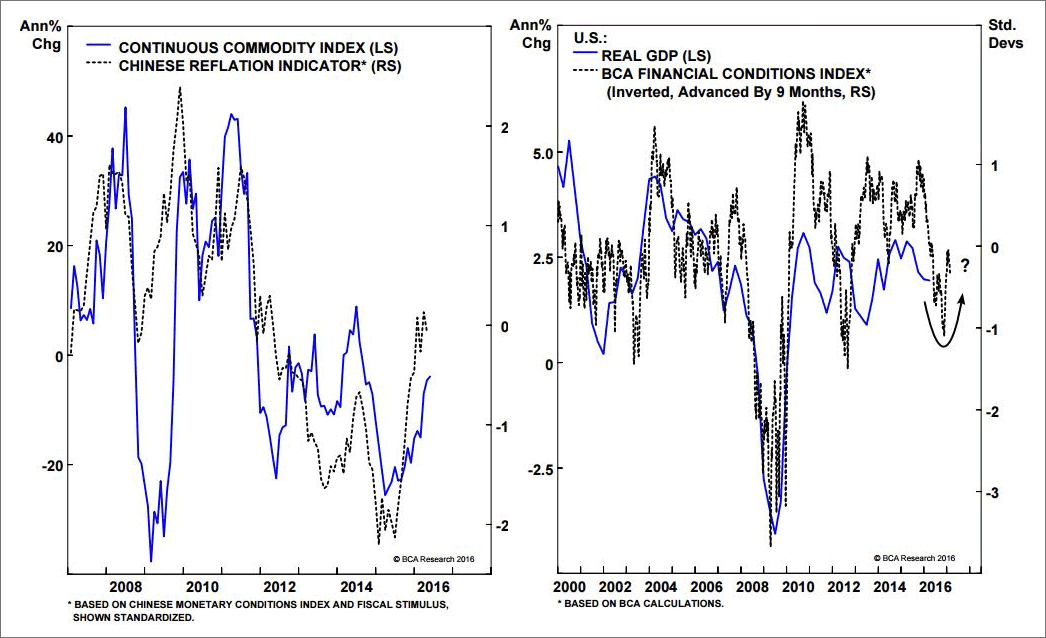

The confluence of a more dovish Fed since mid-February and evidence that China’s policy stimulus is stabilizing growth there has been instrumental in lifting risk assets over the last quarters. Two macro dynamics are critical to the outlook for the longevity of the reflation trade: 1) Chinese policymakers’ ability to wean the economy off its dependence on credit without torpedoing growth there and in the rest of the emerging world, and 2) the Fed’s reaction function to how global growth and easier financial conditions impact the US outlook.

China’s reflationary impulse faces the stiff structural headwind of a massive build-up of private sector debt, now over 200% of GDP, towering over even the elevated leverage in advanced economies. China now needs four units of credit to generate a single unit of GDP. Firms are generating less free cash flow: accounts payable relative to sales for Shanghai-listed industrial, material, and property development firms are surging, and non-financial firms’ receivables are also rising even as credit growth booms. Firms are using new borrowing to pay bills rather than invest in new projects.

But Chinese households save 41% of disposable income, much more than other major economies. Savings leads to more capital investment in the absence of intermediation through the household sector. Understanding the macro implications of a persistently high savings rate informs the odds of the Chinese government being able to reduce the economy’s dependence on credit-intensive investment while sustaining growth. A country’s current account balance is simply the difference between savings and investment. To the extent that a country like China over saves, those savings must be intermediated through domestic investment or exported to the rest of the world via a large current account surplus. China’s credit growth began to accelerate in 2009, precisely when the current account surplus started to narrow. When savings stopped finding an outlet abroad, it started to be transformed into investment via the domestic financial system; savers funneled money into bank deposits which got lent out to willing borrowers.

Fortunately, as long as a country has ample domestic savings and borrows primarily in its own currency, debt can increase without hitting the proverbial ‘debt wall’ as fast as many expect. In China’s case, non-performing bank debt is also largely self-contained as it consists of loans made by state-owned banks to state-owned enterprises and local governments, which will cushion the eventual cleanup process. But China doesn’t need to face an imminent systemic financial crisis to be a source of deflationary pressure for the global economy in general and the rest of the emerging world in particular. China’s difficulty in shifting the economy away from its high reliance on investment means it will sustain excess capacity in a number of industries, particularly in the manufacturing sector which continues to deflate. This is good news for bonds, but bad news for global industrial corporate pricing power, as it depresses China’s demand for imported capital goods, largely procured from other emerging market nations whose growth will slow as a consequence.

From the Fed’s perspective, however, China’s efforts to stabilize its economy have quelled fears of a sharp global growth slowdown that ravaged markets earlier in the year. Minutes from the Fed’s April meeting revealed a renewed hawkish tone which prompted markets to discount higher odds of at least one more rate hike this year. From the history of the last 20 years, the unemployment rate doesn’t need to drop much further for wage growth to accelerate, leading to a pickup in core inflation.

Risky assets have been trading in a wide range since late 2014 as proxied by the total return of the stock to bond ratio. We have seen three episodes of the ratio hitting the top of its range, leveling off, and then selling off abruptly. In each case, the catalyst for the sell-off in risk assets has markets discounting an overly restrictive Fed, with the 10-year yield topping out corresponding to the tipping point for the stock to bond ratio. Bond yields and rate expectations remain benign for now, but will grind higher in the next few months as markets continue to digest the Fed’s commitment to resuming the tightening cycle. The other warning sign for risk assets is the renewed weakening in the Chinese renminbi. Sharp setbacks in US equities last summer and earlier this year started with a depreciating Chinese currency. The recent stall in China’s growth reacceleration despite aggressive stimulus challenges the longevity of the mini reflation cycle we’ve seen in the last three months.

To find out more, click here to listen to BCA Chief Strategist Caroline Miller’s May 26th Webcast.