Sailors know by experience and by reputation to fear rogue waves. Once thought to be the product of human imagination or seafaring myths, today rogue waves are being studied by scientists around the world. With wave heights recorded at 100 feet and more, these giant monsters of the sea occur more frequently than once imagined. Over the last two decades rogue waves are believed to be responsible for sinking dozens of ships and taking countless lives. In the words of Wolfgang Rosenthal, a German scientist responsible for helping the European Space Agency track rogue waves by radar satellite, "I hope I never met, and hope I never meet, such a monster." [1]

Unlike the tsunamis, which are created by a single earthquake, the forces behind these killer waves are created by several extreme conditions. The harder the wind blows, the bigger the waves become and the more wind they catch. These waves become a sail and are able to harness the energy of the wind. Their heights are determined by three factors: wind speed, its duration, and the distance (fetch) over which the wind blows. The big ones are unpredictable. They originate from a direction that is different from the predominant waves in the local area. They seem to appear out of nowhere and can spell disaster when they occur.

We have been experiencing similar phenomena, like the ocean's rogue waves in the world's financial markets. The global financial system has been buffeted by a series of rogue financial incidents from the stock market crash of 1987, to the peso crisis of 1994, and the Asian and Russian debt defaults of 1997 and 1998, as well as a series of hedge fund blowups, Amaranth Partners being the most recent. These rogue financial events seem to occur more frequently whenever extreme financial speculation and oceans of credit pervade the financial system, as they do today.

Rampant Debt and Speculation

It isn't just a matter of rising debt levels. It is the fact that more of that debt is going into financial speculation. This should be of great concern to Washington, Wall Street and Main Street.

Debt and speculation have become ubiquitous in the global financial markets. Yet as debt levels have risen, raising the degree of risk in the financial system, the degree of complacency has also risen along side of it. It is evident everywhere, from declining stock and bond market volatility to declining option and credit spreads.

Declining Option and Credit Spreads

In the current global low-interest-rate-environment, investor appetite for risk has become insatiable. Institutional players scour the globe in search of a few extra basis points for performance, disregarding risk in the process.

As debt levels have risen, so has the degree of leverage in the derivative markets. According to the latest data from the BIS (Bank for International Settlements) outstanding derivative contracts exceed 0 trillion! As shown in the rogue wave-looking graph below, the derivative market has grown by double digits every year.

The majority of these derivative contracts are interest rate-related. At the moment there appears to be no limitation as to the number of permutations of this type of investment arising from this sector.

Derivatives on the Increase

Credit Default Swaps

The latest craze in the derivatives market is the CDS or Credit Default Swaps. Credit default swaps provide a method for investors in debt securities to cover their risks by buying insurance on the bonds they own. Designed originally as risk insurance, they have now taken on a speculative veneer.

This speculative danger was no more evident than last year's General Motor (GM) Credit Default Swaps situation. At the time of the decline of GM bonds, the number of credit default swaps written against these bonds far exceeded the bond issue. As rumors circulated that credit agencies might downgrade GM debt, the credit spreads that were being paid to accept this rising risk in credit default swaps kept becoming bigger and bigger. The spreads became so attractive that they garnered the attention of hedge fund managers lured by their juicy returns. These managers began writing credit default swaps on GM bonds in exchange for healthy premiums without tying up any of their own capital.

As a means of mitigating their risk, they hedged their exposure to a GM credit downgrade by shorting GM stock. If the stock dropped as a result of the downgrade, they could use the profits from shorting GM stock to offset the losses on their credit default swaps.

Fine in theory. The hedge worked until an 88-year-old billionaire launched a per share tender offer to buy as many GM shares as possible. The theory worked until Mr. Kerkorian showed up out of the blue, just like a rogue wave, creating billions of losses for the hedge funds, whose short positions were destroyed by the following rise in GM share price. On the other side of the trade, many investors who had purchased the GM credit default swaps never actually owned the bonds. Like auto insurance when you wreck your car, you must turn in the wreck to the insurance company to collect your payment. The problem for these GM swap investors was that many who purchased the GM default swaps didn't own the bonds. No problem. The transactions were settled on a cash basis.

The financial system has learned to adapt to these rogue wave events by allowing for cash settlement instead of payment in kind. Therefore, speculation has been allowed to grow unabated by regulatory checks. Since the GM fiasco, credit default swaps have continued to grow from .4 trillion at the end of 2004 to the third quarter of this year where they stood at .4 trillion.

Constant Proportion Debt Obligations

The permutations of debt in this current financial market continue. The latest variation on this theme is the CPDO (Constant Proportion Debt Obligation). In an inflationary world starved for yields, this is the latest leveraged product to appeal to those who want higher yields as well as safety. You would think the two concepts would be mutually exclusive. True in theory, but not in the high-roller-investing derivative markets where it is said you can have your cake and eat it too.

Designed to look like an ordinary bond, its attractiveness comes from its higher yield and its triple-A rating. Generally, CPDOs pay about 200 basis points above LIBOR (London Interbank Offered Rate) How can a triple-A rated bond pay such a high rate? It is all in the way the derivative is structured. The derivative is set up through a SPV (Special Purpose Vehicle) which invests the proceeds used through a bond sale in cash equivalents deposited at a bank. To increase the yield on the bonds, the bank enters the derivative markets by selling credit default swaps. The premiums earned through writing credit default swaps go back to the bank and the SPV. These premiums, when combined with the interest earned on the bank deposit, are what create the higher yield.

The bonds carry a triple-A rating because of the insurance banks carry to back their deposits. However, in essence what the banks are doing is laying down a one-way bet on the creditworthiness of the constituent companies that make up a bond index which is refreshed with new companies every six months. The CPDOs add leverage to the bond transaction that begin their life with a leverage factor of 15.

Does this scenario sound familiar? It should. The CPDOs sound a lot like a similar transaction called a CPPI (Constant Proportion Portfolio Insurance) from the 1987 stock market crash. CPDOs allow the bank to put on more leverage if the trade begins to go the wrong way. The bigger the losses, the greater the degree of leverage. In other words, if the trade goes against the bank, the bank can increase the amount of the constant proportion portfolio insurance it writes in an effort to cancel out the risk. As the following graph illustrates, those basis points in premiums are getting rather thin; hence the rise in the amount of leverage.

Mammoth Credit Expansion in all Segments

If there is one thought that permeates today's credit markets, it is that the specter of a credit crash seems too remote, even unthinkable. Yet the amount of leverage continues to rise scaling heights, never seen before in financial history.

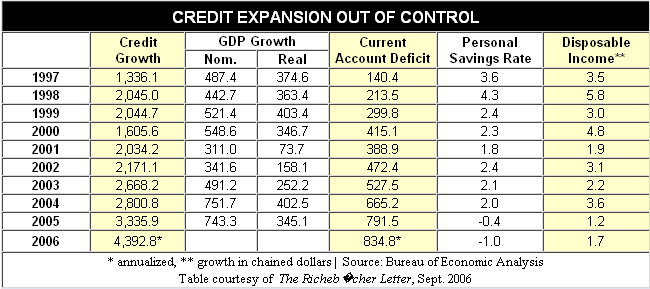

Commercial and Industrial loans have grown by 16.5% over the last three months and by 14.4% year-over-year through November. Commercial bank credit is up 9.5% over the last 12 months. Real estate loans have expanded at a 14.4% rate year-to-date. Total credit creation should expand by 32% this year from ,335.9 trillion to an estimated ,392.8 trillion.[2] Despite rising short-term interest rates, adjustable rate mortgages (ARMs) aren t going away. According to RBS Greenwich Capital, option ARMs made up 15% of mortgage originations in the first half of the year, up from 8% for all of last year. As Doug Noland writes each week in his Credit Bubble Bulletin and as the numbers above indicate, the credit bubble is alive and well.

Debt is pervasive everywhere you look within the U.S. economy. If the rest of the world manufactures goods, then America manufactures credit to buy the goods that the rest of the world produces. It is not only consumers who have taken the debt plunge, but now the big banks, investment houses, REITs (Real Estate Investment Trusts), and private equity firms are also taking the plunge. Wall Street firms are buying subprime lenders in order to feed their mortgage pools, which can then be sold off to professional investors. Recently Merrill Lynch bought First Franklin Financial, Morgan Stanley bought Saxon Capital, and GMAC, the mortgage financing division of GM, is set to be sold to Cerberus Capital Management, a New York private equity firm. The titans of finance are jumping headfirst into the mortgage business at the same time that the people who know this market best are scaling back.

The goal of these acquisitions is to obtain a steady pipeline of mortgage loans that will be fed directly into mortgage pools. The ultimate risk will be laid on the individual investors, mainly institutions. In a world starved for yield, the demand for mortgage products has become insatiable, which in turn has spawned permutations and spin-offs; the latest permutation being the CPDO.

Behind this frenzy of risk-taking has been the expansion of global liquidity. Contrary to popular media opinions, liquidity is more than able to feed the insatiable demand for credit, whether it is a homeowner extracting credit via a home equity loan, a hedge fund using leverage to increase its returns earned from arbitrage, or a private equity firm snapping up a public company. Central banks may be raising interest rates in an effort to temper the speculative fever, but they are also making sure that the engines of credit creation are constantly replenished through the purchase of treasury securities. Foreign central banks have also been active with the purchase of U.S. Treasury debt, thereby increasing their holdings from .5 trillion to .7 trillion in the last twelve months.

Pandora's Box Has Been Opened

As the table above illustrates, broad money supply growth around the globe is running at high single digits or in some countries at double digits.

Shown in this table and the graph below, central banks around the globe continue to churn out the oceans of money that fuel the global financial system. That is the reason why asset markets are rising globally.

It is because the world is awash in a sea of liquidity that central banks will no longer be able to hide the menace of inflation. The Pandora's box of inflation is now open and the inflation genie has been unleashed upon the world's financial markets and economies around the globe. Inflation (not deflation) will be the order of the day.

Austrian economists have long understood the consequences of unbridled money creation as the chief cause of our boom and bust cycles in the economy. They also understood that economic recessions could be postponed, if enough money creation or loans not backed by real savings were created within the financial system. In order to forestall the consequences of the boom (recession or depression), they understood that it is necessary to create credit at an ever-increasing rate. This is what is now being done globally as illustrated in the table of credit creation from The Richebächer Letter. Please note the degree of credit expansion and its acceleration since the Fed began its rate-raising cycle in the summer of 2004.

As the Fed was raising interest rates 25 basis points at each of its 17 meetings, it was also making sure that the credit engines of the banking system were constantly supplied and cashed up. Total credit growth expanded by over .7 trillion from the time the Fed began raising rates in June of 2004 to the time it went on pause this past summer. This can hardly be considered "tight liquidity conditions" as so often reported by the financial media. The fact is that credit is being created at a faster rate than what is commonly perceived by the financial markets. Instead investors are treated to financial propaganda designed deliberately to confuse. So we hear the constant blather about the Fed's concerns over inflation, the "core rate" and other useless nonsense that takes investor attention away from what matters most: money and credit are being created at an accelerating rate as demonstrated by the table above.

In order to avoid the inevitable bust, credit expansion must proceed at a speed at which investors cannot anticipate. Additional doses of credit are given to companies to launch new investment projects, hedge funds to increase their returns from arbitrage, or private equity funds to use increasing amounts of leverage in order to make their ROE (Return On Equity) assumptions work out. I pointed this out earlier by citing that commercial and industrial loans are growing at 16.5% and commercial bank credit is expanding at 9.5%.

Postponing the Inevitable a While Longer

This expansion of credit at increasing rates may postpone a recession or a depression for a very long time. That is why business cycles have expanded in duration since the early 1980s. However, this postponement comes at a cost. In the end the delay usually leads to deeper and much more painful recessions or in a worse case an actual depression. Austrian economist Murray Rothbard addressed this deferral and its consequences in his magnum opus, "Man Economy, and State."

Why do booms, historically, continue for several years? What delays the reversion process? The answer is that as a boom begins to peter out from an injection of credit expansion, the banks inject a further dose. In short, the only way to avert the onset of the depression-adjustment process is to continue inflating money and credit. For only continual doses of new money on the credit market will keep the boom going and the new stages profitable. Furthermore, only ever increasing doses can step up the boom, can lower interest rates further, and expand the production structure, for as prices rise, more money and more money will be needed to perform the same amount of work

But it is clear that prolonging the boom by ever larger doses of credit expansion will have only one result: to make the inevitably ensuing depression longer and more grueling. The larger the scope of malinvestment and error in the boom, the greater and longer the task of readjustment in the depression.

The way to prevent a depression, then, is simple: avoid starting a boom.[3]

This is where we find ourselves today. Central bankers are trying to avoid the inevitable, to make the clouds go away so the sun can shine for one more season. In order to accomplish this task it is necessary to quicken the rate of credit creation. Credit and money creation must now increase at a rate faster than the rise in consumer prices. Consumer prices increase as new money creation creates greater demand, which drives up prices in the process. Higher prices then require even more money creation to pay for the cost of goods which have risen in price due to the effects of inflation created by the credit expansion.

Therefore credit expansion must accelerate going forward in order to avoid a bust. However, it must do so at a rate that is not detectable by investors. If inflation expectations were to increase and spread, the prices of consumer goods would soon begin to rise even faster than the prices of the inputs of production. An additional consequence of rising inflation expectations would be a concomitant rise in market interest rates. That is why you now see the Fed targeting inflationary expectations as they did in May and June of this year when the Fed s Open Mouth Committee was working full time giving anti-inflation speeches almost on a daily basis. It worked. Inflationary expectations came down, more money and credit were created, and interest rates fell.

Central banks, especially the Fed, are attempting to ward off a recession even as inflation rates rise. However, unlike the past recession, mild by comparison to those that preceded it, inflation throughout the monetary system is running rampant. This can be viewed through myriad asset bubbles around the globe in equities, bonds, mortgages, or real estate. It can also be seen in narrowing credit spreads, low interest rates, the tremendous rise in speculative capital, and the level of complacency by investors.

In the end the piper must be paid. Central banks cannot avoid the inevitable crisis forever. Sooner or later the rogue wave will arrive triggered by either of three likely scenarios:

- The rate at which credit expansion accelerates either slows down or stops due to bankers' fears of taking on more debt due to experienced by rising defaults in their loan portfolios. (Think S&L crisis, 1991.)

- Credit expansion grows at a rate that does not accelerate fast enough to prevent the effects of economic reversion.

- Investors and consumers wake up to the fact that they have been fooled. They begin to realize that inflation rates are rising as they personally experience inflation. The inevitable flight to real assets commences as it did in the 1970s. This creates accelerating money velocity causing the prices of goods and services to escalate, which eventually leads to a collapse of the currency. [4]

The third scenario is where I believe we evenutally are heading. It could take three to four years, maybe longer if we get lucky. For now all stops will be pulled out to postpone the crisis. The Fed knows it needs to bring rates down, but that is difficult under present circumstances. Unlike 2001, commodity prices are no longer tame. In 2001 when gold was selling at 0 an ounce and oil was under a barrel the Fed had more leeway in lowering rates. The only visible inflation at that time was in equities, especially tech stocks. So the Fed could ease aggressively as it did in the recession of 1991.

Fast forward to today and the signs of monetary inflation can be seen everywhere from asset bubbles to the prices of goods and services. Monetary inflation has been so pervasive that it can no longer be so easily hidden. Lowering rates today even as monetary expansion continues will take a lot more finesse. Today the Fed needs a deflation scare or a reason to lower rates, like a financial crisis. Back in 2003 we got the deflation scare brought on by a change in how the CPI was measured. Owners-equivalent rent was used in place of rising home prices and used car prices were substituted for new car prices. [See The Core Rate.] The effect of these substitutions was to lower the CPI from over 3% to 1.6%. Rates came down precipitously with the 10-year note falling to 3.5%. Something similar will have to be manufactured next year for rates to come down. You could get a deflation scare with falling real estate prices, a slowing economy, and lower manufactured goods prices as excess inventories are worked off, and a gradual or sharp drop off in consumer demand.

Even more likely could be a combination of the above, coupled with a financial incident caused by a major bankruptcy in a high-profile company or a wave of bankruptcies in the subprime lending market. This could also trigger a chain reaction in the derivatives markets with credit default swaps. If these events were to unfold, the Bernanke Fed would lower rates and flood the financial system with an ocean of money faster than you could blink your eye. The inevitable wave of money would then flow over into the financial markets, creating additional asset bubbles in equities in much the same way as the Asian crisis, the Russian debt default and the failure of Long Term Capital Management in 1997 and in 1998.

What Lies Ahead and What to Expect

This potential credit-infusion-induced chain of events could make 2007 all the more interesting. Expect something like a "financial" rogue wave to emerge out of nowhere and take the markets by surprise. You also need to anticipate a Fed response, if such an event occurs, to be massive leading to greater asset bubbles and higher rates of inflation.

Expect that rogue wave to emerge from the subprime lending markets. That is from where I believe the real credit problems will originate. The charts below of the subprime lenders are already forecasting trouble.

Also keep your eyes on Ford Motor Company (F). According to recent press releases, the company has pledged nearly all of the company s assets from factories and equipment to Ford Motor Credit in an effort to obtain billion in desperately needed loans. It is the first time in the company s 103-year history that it has been forced to pledge its core assets as collateral. The company is currently burning cash at a rate of billion a year. The current rate of hemorrhaging will leave the company with no cash to pay its bills within less than three years. Ford gave up its investment grade rating last year. It s junk bond status has forced the company to pay higher interest rates and thereby raising its cost of capital.

As the "Past Financial Crises - Fed Tightening Cycles" chart demonstrates, every Fed rate-raising cycle has ended up breaking something either in the economy or in the financial markets. There have also been instances when the Fed has broken both the economy and the financial markets. If they raise rates high enough, we'll likely get a recession as we did in 2001 as a result of the 1999-2000 rate-raising cycle.

Looking back over the last three decades, there have been at least a dozen such episodes that erupted in the wake of the various Fed tightening cycles. So far, real estate is falling, the economy is slowing, but we have had no major financial mishaps. But it is still early and the fallout from real estate has much further to run. Watch the credit markets especially subprime lenders. And watch the U.S. dollar. I am assuming Hank Paulson and Ben Bernanke went to China for other reasons than "to see The Great Wall." I suspect their motive is to obtain Chinese cooperation in devaluing the dollar.

Expect to hear more stories like Ford next year. It is this emerging debt crisis whether from heavily leveraged manufacturers such as Ford, subprime lenders, overleveraged hedge funds making one-way bets, or the derivatives markets that should create the next rogue wave. When I wrote Rogue Wave/Rogue Trader in October 2000, I highlighted two possible scenarios: one financial and the other geopolitical. It was the geopolitical scenario that unfolded first. This time I expect it will be financial.

I'll end with something I wrote back then as I believe it is still relevant to the world we live in today:

There will come a day unlike any other day, an event unlike any other event and a crisis unlike any other crisis. It will emerge out of nowhere at a time no one expects. It will be an event that no one anticipates, a crisis that experts didn't foresee. It will be an exogenous event, a rogue wave.*

Resources:

[1] Broad, William J, "Rogue Giants at Sea," New York Times, July 11, 2006.

[2] Richebächer, Kurt, Richebächer Letter, September 2006, p.11.

[3] Rothbard, Murray N., Man Economy, and State, Ludwig Von Mises Institute, 1970, pp. 861-862.

[4] Jesus Huerta De Soto, Money, Bank Credit, and Economic Cycles, Ludwig Von Mises Institute, March 2006, pp. 397-408.

* Puplava, James J., The Perfect Financial Storm, Rogue Wave/Rogue Trader, October 26, 2000.