It’s happening again. Gasoline prices are on the rise. Since bottoming nationwide last September 29th at $2.69 a gallon, they have risen to $3.698; up $0.30 in the last month. The blow-dry’s on cable television are going bonkers with hysteria trying to explain it. News anchors like Bill O’Reilly are ranting vociferously: “It’s all due to greedy oil companies.” Politicians are blaming speculators. Meanwhile, at the pump the average American is stuck with higher fuel bills to help pay for the weekly cost for commuting to work. We’re less than $0.30 away from taking out the highs reached last summer and only $0.42 a way from surpassing the record set in July of 2008...and it's still only February!

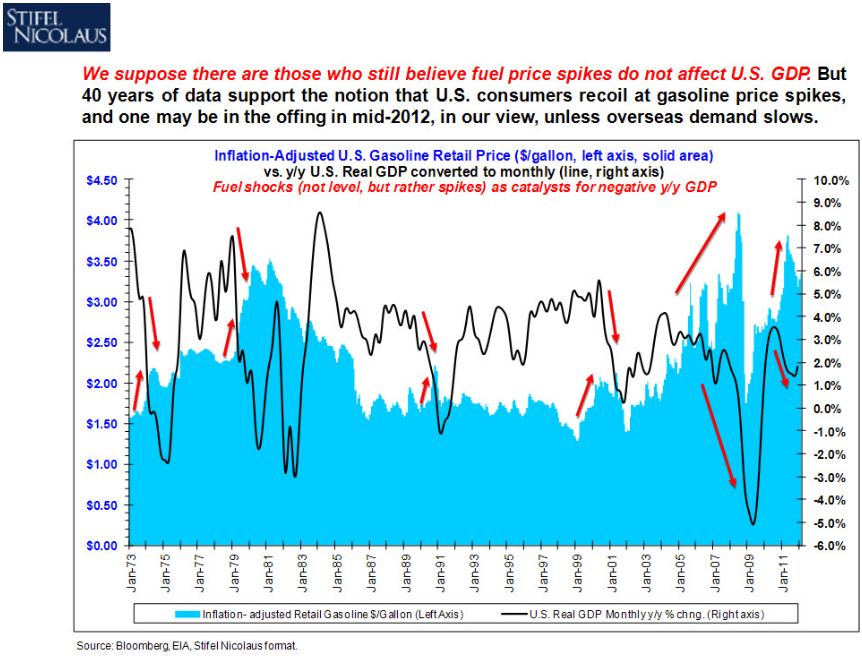

With a weak economy here in the U.S., and in most OECD countries, this should not be happening. Welcome to the new “Petro Business Cycle”—brief periods of economic growth punctuated by short periods of economic slowdown as the result of high energy prices. Not only has this been a pattern we've been experiencing more strongly since the last recession, but also one that has repeated itself over the last few decades as seen in the graph below of gasoline prices and GDP growth.

As the economy emerged from recession in March of 2009 gasoline prices climbed from a low of .61 at the beginning of the year to a year-end price of .65. By late spring of 2010 we were back to a gallon nationwide. The economy began to sputter during the early summer months causing the Federal Reserve to reverse course from planning an exit strategy to announcing QE2. From the time QE2 was announced and implemented, the price of oil and gasoline began to surge again. WTI oil hit a high of 3.92 a barrel on April 29th, 2011 and the price of Brent peaked at 6.65 on April 8th. The result was the LEI’s peaked in the spring of 2011 like they did the previous year. This led to a major slowdown in economic growth repeating a similar pattern experienced in the previous year.

The slowdown produced another round of stimulus in the form of monetary easing (Operation Twist, the extension of low interest rates until 2013 & 2014) and another round of fiscal stimulus through the extension of the payroll tax cut. As much as the Fed and the government would like to take credit for the surge in economic activity, the greatest stimulus came in the form of lower energy prices. From the May 4th peak in gasoline prices of .985 a gallon, gasoline prices plunged __spamspan_img_placeholder__.78 by year-end. Oil prices bottomed at a barrel on October 4th. From that point forward the economy began to improve. The LEI’s began to turn up, consumer confidence improved, GDP picked up steam, and the stock market recovered, with the S&P 500 rising to a present gain of around 25%.

So here we are again with oil prices rising and gasoline prices escalating at the pump. This week’s economic numbers indicate the economy is on the mend. The question is for how long? Which brings up the issue of today’s rising gasoline prices. Is it greedy oil companies, a favorite rant proffered by Bill O’Reilly or is it those evil oil speculators as Nancy Pelosi suggests? Or could it be something else that is at work here? I would like to suggest that it is neither of the two but a combination of forces that are all working concurrently to drive gasoline prices higher at the pump.

They are as follows:

- Geopolitical risk of supply disruption

- Declining gasoline supplies

- Refinery profit margins

- Growing global supply/demand imbalances

I want to begin with what’s behind the recent hike in gas prices first. It’s all in the headlines. The current spike according to Daniel Yergin of Cambridge Energy Research Associates is due to the West’s current confrontation with Iran and sanctions over that country’s nuclear program. In a recent CNBC interview, Yergin said “Right now the market focus is on a tightening of supply, because the whole direction of these policies is to do one thing, which is to reduce Iran’s ability to export oil.”

According to a recent IEA report, Iran currently produces about 3.45 mbd (million of barrels per day). It also consumes over 1 mbd internally, leaving only 2.6 left for export. Most of that export is to China, India, and Japan, which make up 42.5% of Iran’s exports globally. Replacing 2.6 mbd will not be that easy. Last year the loss of Libyan oil exports of 1.6 mbd drove oil prices to post recession records before they subsided. There also can be no comfort in our reliance on two big cushions to stem price increases: Saudi Arabia and the US strategic petroleum reserve.

In a recent press conference designed to calm markets, Saudi assurances were less than reassuring. As it turns out, Saudi spare capacity is far less robust than the market thought. “Of the 12.5 m barrels per day declared capacity, 700,000 falls outside the widely agreed definition of spare capacity - it won’t be available for three months. And if the kingdom is currently producing 10 mbd, the immediate available capacity might be a paltry 1.5 mbd, far less than the safety valve needed to convince markets that prices won’t rise.”[1]

There are other problems with the second big cushion: The U.S.’s Strategic Petroleum Reserve. The claim of being able to draw out 4.4 mbd is proving also to be elusive. During the Libyan crisis the U.S. was only able to release 500,000 bd (barrels per day) due to logistical changes in the way oil flows throughout the system. The latest data show the ability to withdraw less than 800,000 bd. Logistics require seaborne exports versus the original plan to pull inventory through a pipeline system. Port congestion impedes tanker loadings at SPR terminals limiting the withdrawal rate to one seventh of the planned rate into pipelines. The latest plan to bring Canadian oil to the Gulf Coast, the Keystone Pipeline was nixed by President Obama. Thus, a contributing factor for why prices are rising is that the markets have little faith that either Saudi Arabia or the SPR can speedily make up the difference in the loss of Iranian exports.

The possibility of a conflict with Iran, which could come as soon as this fall has caused the Pentagon to beef up U.S. sea and land based defenses in the Persian Gulf in an attempt to counter Iranian efforts to close the Straits of Hormuz. The military’s Central Command, which overseas U.S. forces in the Gulf is taking tangible steps to prepare for a possible conflict with Iran, from upgrading patrol craft, unmanned drones, to adding small arms on surface ships, rapid fire machine guns designed to shoot down missiles, and additional mine sweepers. The Central Command has asked for a reallocation of 0 million in defense spending to beef up its war fighting capabilities in the region. In addition, the Pentagon has asked for an additional million to improve its largest conventional bunker-buster bomb.[2]

The requests come ahead of an assessment of Iran’s military capabilities which include close to 5,000 mines, coastal air-defense systems, shore based artillery, Kilo class submarines, remote controlled boats, kamikaze aerial vehicles and midget submarines. Apparently the Central Command takes these threats seriously. In a larger sense, over 35% of the world’s oil and 20% of seaborne liquefied natural gas sails through the Straits of Hormuz.

Source: Global Equity Research for Lehman Brothers, pg. 3

The second reason gasoline prices are rising is supplies have been declining. The U.S. has lost 700,000 barrels of refining capacity over the last three months due to the shutdown, or retiring of outmoded, and unprofitable refineries in the eastern U.S. and the Caribbean. This represents almost 5 percent of U.S. gasoline production which has gone offline. Sunoco, Conoco-Philips, and Hess Oil have all shuttered refineries which were uneconomic to retrofit to meet the requirements for removing sulfur from high sulfur crude.

Don’t blame the evil oil refiners. The refining business has become unprofitable. According to analyst Thomas Adolff at Credit Suisse, 31 uneconomic refineries have been shut down in recent years, with two dozen more on the chopping block. According to Adolff refiners earn an average profit of for every barrel they process.[3] That equates to __spamspan_img_placeholder__.26 a gallon, about the average profit over the past decade. Profit margins for big oil have averaged between 7-10 percent over the last decade. By comparison state and federal taxes average __spamspan_img_placeholder__.39 per gallon. Now who is being greedy, the oil companies that do the work of refining oil or the governments that collect a tax?

Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy June 2011, pg. 17

It should also be noted that OECD industry oil stocks have fallen to 2.611 mb according to the IEA. They remain below the five year average for a sixth consecutive month. Forward demand cover fell by 0.7 days to 57.2 days. January build shows a shallower-than-normal build of only 11.4 mb in OECD industry stocks.[4]

A third factor causing a spike in gasoline prices is that it has become more profitable for refiners to sell their refined products in the global market. Because the bulk of world energy demand is coming from the emerging world, oil, natural gas, and refined products can be sold overseas at higher prices. Because of the U.S. energy advantage from fracking and horizontal drilling the U.S is now exporting gasoline. The Keystone Pipeline would have given the U.S. even a better advantage but that is a topic for another day. Suffice to say that many unprofitable refineries are currently being shut down. This is reducing our gasoline stocks. This may come as a major surprise to Bill O’Reilly, but in a capitalistic system the objective of a company is to earn a profit for its owners or shareholders. It is a simple choice, sell more oil domestically at a lower margin or at a loss, or earn a higher profit by selling your product overseas. Seems like a no brainer to me.

No oil company or refiner would ever risk investing billions toward a new refinery or in retrofitting an existing facility with the prospect of losing money. The energy industry is a capital intensive business requiring vast amounts of capital to run. An energy company must earn a required return on its capital or it goes out of business. The reason why so many refineries are being shut down or mothballed is because they are losing money. As pointed out earlier, refiners earn __spamspan_img_placeholder__.26 per gallon of gasoline refined. The government collects __spamspan_img_placeholder__.39 per gallon produced in taxes. You can decide for yourself who is being greedy the oil company or the government?

The final factor driving gasoline prices is a persistent problem we have faced for well over a decade. The supply of energy is struggling to keep pace with demand. While demand has fallen in OECD countries it has grown steadily in non-OECD regions. (Source: BP Energy Outlook 2030, pg. 10)

The final factor driving gasoline prices is a persistent problem we have faced for well over a decade. The supply of energy is struggling to keep pace with demand. While demand has fallen in OECD countries it has grown steadily in non-OECD regions. (Source: BP Energy Outlook 2030, pg. 10)

The two key drivers of energy demand remain population and income. The emerging world is experiencing both of these factors with faster economic growth leading to rising incomes as well as an increase in population. Consider the following facts:

- Over the last 20 years global population has increased by 1.6 billion people and will increase by another 1.4 billion over the next 20 years.

- Global GDP growth is likely to accelerate, driven by low and medium income economies projected at 3.7% p.a.

- Almost 96% of energy growth is in non-OECD countries. By 2030 non-OECD energy consumption is 69% above 2010 levels.

- OECD total energy consumption is virtually flat during this time frame.

- Industry leads the growth of final energy consumption, particularly in rapidly growing economies.[5]

The world we inhabit today is a much different world than the one that existed 10-12 years ago. China has now become the world’s second largest economy after the U.S. According to a recent IEA report we are facing a problematic global economic backdrop leading to a two-speed economic outlook—robust demand in non-OECD countries and falling demand in OECD nations. The result is that oil demand is expected to contract by 400,000 bd in the western world and increase by 1.2 mbd in the non-western world. The result is that oil demand continues to grow. After falling for two consecutive years, global oil consumption grew by 2.7 mbd in 2010. OECD consumption grew by 0.9% or 480,000 bd, a first since 2005. Non-OECD demand grew by a record 2.2 mbd, or 5.5%. Most of that demand growth occurred in China and the Middle East.

We have now surpassed the consumption levels reached in 2008. The IEA estimates that oil demand is forecasted to climb to 89.9 mbd in 2012, a gain of 0.8 mbd, an increase of 0.9% over last year. But where is all that increased oil going to come from? In addition to worries over the loss of Iranian exports of 2.6 mbd, Libyan oil production is still down by 600,000 bpd from its peak before the civil war. Unrest in Yemen has knocked off roughly 250,000 bpd. South Sudan has stopped pumping 260,000 bpd day due to disputes over payments for use of its pipeline and export facilities. Civil unrest in Syria has led to a reduction of output by 200,000 bpd and Nigerian output has fallen by 20,000 bpd.

Is is it really any wonder why oil and gas prices continue to rise? Add it all up: growing geopolitical risks with the possibility of conflict with Iran this year in addition to the loss of additional supply from other Middle East producers, declining gasoline stockpiles due to the shuttering of old and unprofitable refineries, growing gasoline exports due to higher profit margins and losses here in the U.S., and a growing supply/demand imbalance leading to declining OECD industry oil stocks. Perhaps we should be asking: Why are oil and gas prices not much higher!

Do the math. You don’t need to be an industry analyst to understand where this is heading. We are approaching another tipping point. Whether that price will be or .50 nationally at the pump I can’t say. However, every penny increase in the price of gasoline is going to take billions out of the pocketbook of consumers this year.

I believe we are seeing a repetitive pattern that is beginning to emerge. I call it the “Petro Business Cycle.” It is a pattern that I have seen develop ever since we emerged from the Great Recession of 2007-2009. It begins with monetary and economic stimulus which stimulates economic growth. Increasing economic growth leads to greater energy consumption. Increased consumption causes prices to rise as a result of the inability of supply to keep up with demand. This leads to rising prices and rising inflation levels which eventually leads to economic slowdown.

If I’m right about this new economic thesis, the continued rise in oil and gasoline prices should begin to show up in the prices paid component in the regional Fed and industry surveys. Eventually these price increases will be reflected in a slowdown in the LEIs. They should begin to peak shortly thereafter, and then decline along with economic growth. When the LEIs start to roll over the “risk off” trade will replace the “risk on” trade and it will be time to get defensive again. It is a pattern that has played out over the last two years. It looks to me to be playing out once again.

In the misquoted line from Casablanca by Ilsa Lund (Ingrid Bergman), “Play it again Sam.”

[1] Cushions to stem Iran oil price spike are proving elusive, By Ed Morse, 2/27/12 Financial Times

[2] U.S. Bulks Up Iran Defenses, By Adam Entous and Julian E. Barnes, WSJ 2/25/12

[3] Tired of High Gasoline Prices Already? We ain’t seen nothing yet., By Christopher Helman, Forbes 2/23/12

[4] Oil Market Report, IEA, February 10, 2012

[5] BP Energy Outlook 2030, London, January 2012