With the recent expansion of the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), European leaders have taken yet another step to try and contain the euro-area sovereign debt crisis. As part of the arrangement, banks and other private entities will reduce the value of their Greek debt holdings by 50%, thereby recognising what has been a material deterioration in European bank solvency. As a consequence, European banks need to be recapitalised. This should serve to remind investors that the underlying problem in overindebted economies is one of solvency, not liquidity, and that you can’t fight solvency time-bombs with liquidity bazookas. Broadening scope to the global economy, we consider where there probably lie additional solvency ‘time-bombs’ that could explode in future.

Solvency, not Liquidity, is the Real Issue

When the financial crisis began there was an active debate regarding whether the problem was primarily a lack of liquidity in, or the solvency of, the financial system. In retrospect it is obvious that the seizing up of US financial market liquidity in 2008 was a symptom of the insolvency of several major financial institutions which no longer exist. Other clear indications of insolvency were the Fed’s assumption of toxic subprime mortgage assets from Bear Stearns and government nationalisations of Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae.

Recent events in the euro-area demonstrate that, as with the US, solvency is the real issue. While various euro-area sovereign bond markets have been highly illiquid now for months, the recognition that Greek bonds must be written down places the focus back on bank solvency and the need to raise capital.

Financial markets have celebrated Germany’s reluctant willingness to increase its commitment to the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and also some indications by China and even Japan that they might be willing to participate in some way, if the terms are sufficiently attractive.

However, it is highly unlikely that Greece will be the only euro-area country in need of a debt restructuring. At a minimum, Portugal and Ireland are likely to follow, in part on moral grounds: Both have taken austerity measures comparable to those in Greece. Both have comparable accumulated debt burdens. Yet neither has received debt relief, merely temporary liquidity support. That is quite obviously unfair and it is only a matter of time before both of these countries point to the Greek debt reduction as a benchmark for what they, too, now expect. In the event that either Spain or Italy get into similar trouble, then naturally they, too, will point to the Greek example of partial debt forgiveness.

Should additional countries receive the Greek treatment, the EFSF will need to be increased in size from the current EUR1tn. Also, in that event, European banks holding the restructured debt will no doubt find that their solvency deteriorates yet again, in some cases to the point of insolvency. Dexia, the recently nationalised Franco-Belgian bank, will find that it is in good company. Banks in general will thus find they are scrambling, yet again, to raise capital. Those investors foolish enough to inject capital today will find that they are being diluted, perhaps severely.

It is in part for this reason that it is far too early to conclude that Germany’s current, reluctant willingness to further expand the EFSF is indeed firm or that China, or Japan, or any other external source of bail-out support will be forthcoming and sustained. But there are additional reasons why we should be sceptical. As we wrote in our September report, Who Will Rescue the Rescuers?

[O]mitted from this discussion is whether the Chinese and other BRIC economies are going to remain healthy enough to provide a credible backstop for weak euro sovereign debt for a sustained period of time. If China and/or the other BRICs have a hard economic landing, they will have their own bad debt problems to worry about. As sovereign nations, they could, of course, at any time, choose to limit or withdraw entirely their support for any euro-area bail-out arrangement.

In our view, a BRIC hard landing is a material risk. Consider that, back in 2009, various policy stimulus measures in the US, Europe, Japan and elsewhere began to provide significant if temporary support for exports from the BRIC economies. As recent data in the developed economies demonstrates rather clearly, the effect of this stimulus is now wearing off and a renewed downturn is in the works. Should we be confident that the BRICs will be able to decouple?

Absolutely not. Indeed, they might turn down relatively more sharply. Why? Well, for one, BRIC rates of investment have remained elevated, implying much excess capacity in the event that export demand slows. Second, all BRIC economies have been raising interest rates over the past year in response to surging inflation. The lagged impact of higher rates might now be taking effect on growth. Finally, as is always the case with rapidly growing emerging markets, their economic cycles simply tend to be more volatile on both the upside and downside.

This is why certain indications of slowing BRIC economies should be of concern for those who believe that the BRICs will “rescue the rescuers.” There are now several to note.

First, monetary authorities in both Brazil and Russia have taken action recently to ease policy, by lowering interest rates and talking their currencies lower. Clearly they believe that the cycle has now turned. Second, a handful of highly growth-sensitive Asian currencies—the South Korean won, the Taiwan dollar and the Malaysian ringitt—have weakened sharply of late, something that also happened, incidentally, in the early stages of the general global downturn of 2008. Finally, and this is perhaps most obvious, the BRIC stock markets have not been performing well this year, in particular that of China. The Shanghai Composite Index failed to bounce along with global stock markets last week and is closing in on key support at 2,400. If that is taken out, it theoretically opens up downside all the way to the lows the index reached at the nadir of the 2008 financial crisis.

Could it be then, that just as the BRICs step up to “rescue the rescuers”, they, too, find themselves in need of some form of rescue? But with the entire global economy slowing down, where on earth is that going to come from? The moon? Mars?[1]

There is thus good reason for concern that the euro-area solvency time-bombs are going to cause tremendous damage to the global financial system in future. Recent actions may have slowed the ticking clocks, but what is really needed is to defuse the bombs. That, however, would require action to fundamentally improve euro-area economic competitiveness and potential growth. Lost in the celebration that a crisis has been averted in the near-term is this important, unavoidable, unfortunate fact.

Solvency Bomb Detection

Let’s shift the focus away from the euro-area for the moment and consider where else some solvency time bombs might be ticking away. Across the Channel in the UK, there are almost certainly solvency issues with the financial system, which was to a significant extent nationalised in 2008, precipitating a dramatic, 25% decline in the value of the pound sterling versus the dollar.

The UK is the only major economy to have benefited from a substantial devaluation of its currency since the onset of the financial crisis. Yet while this has supported growth, it has also contributed to a large rise in consumer price inflation, now over 5% y/y, far above the Bank of England’s 2% target rate.

In this context, it is instructive to consider why the Bank of England recently voted to expand its bond buying programme. One would have thought, given the elevated rate of inflation, that they would have bee reducing it or raising interest rates instead.

There are several possible explanations for this apparently inconsistent behaviour. First, the government is pushing forward with an austerity plan. Although nothing like what is happening in Greece, Ireland or Portugal, it is nevertheless a significant growth negative for the economy, at least in the near-term. As the central bank stands by, watching the government make good on its commitment, they might believe that they are doing their part to help offset the fiscal policy contraction with some additional monetary policy expansion.

Second, notwithstanding currently high inflation, the Bank claims that, looking forward, inflation is likely to decline significantly over the coming quarters. While that might be true—sterling has been stable over the past year and the economy is weakening again—the Bank has been consistently expecting lower rates of inflation since late 2009. Two years later, this talk is starting to sound a bit hollow. By implication, it would appear that the Bank is deliberately seeking a prolonged period of inflation substantially above target, rhetoric to the contrary notwithstanding.

If true, this helps to explain why the Bank continues to increase asset purchases. But it raises a troubling question: Why? Why is the Bank deliberately aiming for higher inflation?

Well, consider that UK banks have an exposure not only to Greece but also other weak euro-area sovereigns. They also have a huge exposure to the domestic property market, which by any reasonable measure remains fundamentally overvalued.

In the event that additional euro-area members come seeking debt relief along the lines of Greece and the UK property market begins to weaken alongside the domestic and global economy, UK banks might find they are in need of yet another government rescue. The BoE’s actions suggest that they are attempting to pre-empt a potential solvency crisis. There could well be a solvency time bomb in the UK financial sector which, it should be noted, is large relative to the domestic economy.

Having taken a look at the UK, let’s turn to the US. Notwithstanding a somewhat stronger Q3 GDP print, at 2.5%, a broad range of leading indicators paint a picture of slower growth ahead in the coming quarters. Perhaps this should be no surprise, as the huge amount of stimulus thrown at the US economy in 2009 and 2010 has largely run out, and the Fed has so far held back on implementing yet another round of quantitative easing.

In that context, it should be deeply worrying that US financial companies are already suffering. Earnings at major banks might look alright, but this is due largely to so-called ‘debt valuation adjustments’: US banks have marked down the value of their outstanding liabilities as credit spreads have widened, artificially inflating current earnings.

While not strictly dishonest—the regulators allow banks to do this, as long as it is disclosed publicly—it does highlight the glaring inconsistency in US banks’ accounting practices. On the one hand, they can write down their liabilities, inflating earnings. On the other, they are under no obligation to mark their non-trading assets to market. Yet the very reason why the liabilities have declined in value is because financial markets perceive deteriorating asset quality! (The banks must disagree with the financial markets as they have been reducing their loan loss reserves.)

It gets potentially much worse. Recently, Bank of America moved some $75bn of trading assets from the parent holding company into a subsidiary, in a rather desperate move to shore up capital. While the Fed approves of this action, presumably because it prevents the need for Bank of America to raise fresh capital under market duress, it has received scrutiny from the FDIC. This is because the subsidiary is insured by the FDIC, whereas the parent company is not. In the event that the subsidiary becomes insolvent, perhaps because these trading assets decline in value, then the FDIC, backed by the taxpayer, will be on the hook.

It is a sign of the times that a major US bank would resort to such desperate measures to shore up capital. Even more telling is the Fed’s willingness to allow this to go ahead. So while the Fed may be holding back on additional stimulus for now, it is clearly aware of deep problems at Bank of America, an institutional that is no doubt Too Big to Fail.

None of these accounting actions would be necessary were only liquidity, rather than solvency, at issue. The fact that they are taking place therefore triggers our solvency bomb detector. All is not well in the US banking sector, and if the leading indicators are right and the economy slows in the coming quarters, things are going to get worse.

Let’s examine the issue of US bank asset quality in more detail. What assets are at risk of writedowns and writeoffs? Well, with the unemployment rate still elevated and the workforce not growing, household credit quality is not improving. With the household savings rate still unusually low in a historical comparison, there has been minimal improvement in household balance sheets. Indeed, the household savings rate has declined again recently. Significantly higher savings rates, for a sustained period, would be required for proper balance sheet repair.

U.S. Households Savings Rate is Already Back to Pre-Recession Levels

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA)

US state and municipal governments are also under growing financial stress. Several cities and counties have already declared bankruptcy, with many others considering this option as a way to get their expenses under control. US banks are big lenders to these entities, so the trend is indicative of worsening bank asset quality going forward. Here lie additional solvency time bombs.

Meanwhile, the US federal government is running a huge, double-digit budget deficit in a desperate attempt to stimulate the economy and get it growing again. Before the year is out, US government debt outstanding will be in excess of 100% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), a ratio well above that which normally triggers a sovereign debt crisis.[2] That said, as a sovereign entity with a central bank which, although nominally independent, has shown every willingness to purchase more government debt as required to finance deficit spending, solvency is not at issue here. The US government will not default, not in a traditional sense anyway. Rather, the risk is to the dollar itself, which is likely to continue to decline in purchasing power as long as the deficits continue.

The Misplaced Hope in Corporations

With households and non-federal public entities a source of clear solvency risk for the US financial system, we now turn to corporations, which on the surface appear much healthier. Profit margins are historically large and liquidity is ample. Indeed, the US corporate sector appears so strong in relation to households and the public sector that many commentators assume that corporates are going to pull the broader economy out of its slump. All they need do is start investing their spare cash in new plant, property, equipment or inventory. The jobs will then follow, and with them the incomes that generate the requisite final demand.

While this argument is superficially plausible in that it would represent a fairly typical business cycle recovery, a look beneath the surface shows that it is really just a misplaced hope. Returning to our distinction between liquidity and solvency, just because corporations are liquid does not imply strong solvency. And if solvency is not particularly strong, and economic uncertainty generally elevated, it is unrealistic to expect corporates to invest a meaningful portion of their spare cash.

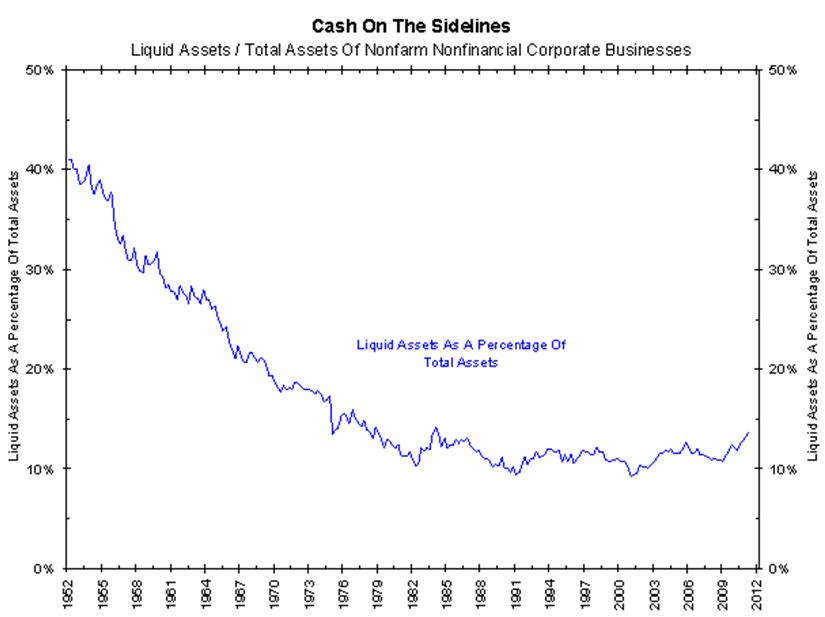

Before we investigate corporate solvency, let’s take a closer look at corporate liquidity. Just how liquid are US corporates? At first glance, they appear highly liquid. Total corporate cash holdings have soared in recent years, as seen in the chart below:

U.S. Corporate Cash Balances Have Soared Over the Past Few Decades...

Source: US Federal Reserve

While that might look rather impressive, consider that there has been a veritable flood of dollars created in recent years, as a result of highly expansionary US monetary policy. While much of that cash exists as bank reserves, in particular those created by the Fed in response to the recent financial crisis, much of it has found its way onto corporate balance sheets.

The flip side of massive money creation, however, has been rising asset prices. More money chasing the same amount of assets results, of course, in higher prices for the latter. This effect shows up on corporate balance sheets. Cash balances may have soared, but so have asset values generally, such that the ratio of the former to the latter is, in fact, relatively low in a long term historical comparison.

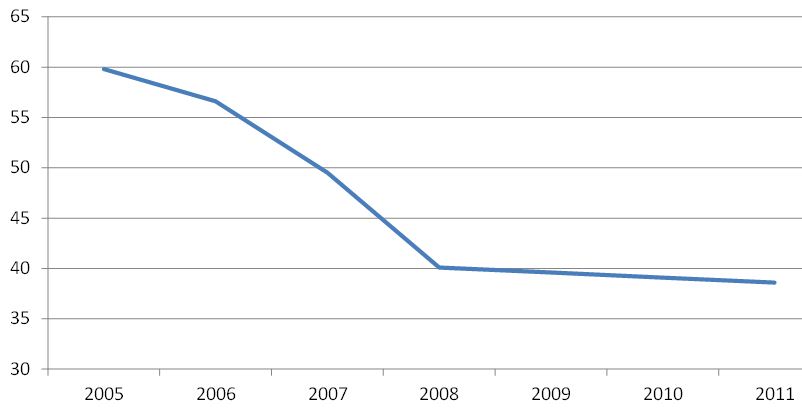

...But as a Percentage of Total Assets, It Remains Within the Mult-Decade Range

Source: US Federal Reserve

To be fair, there has been a material rise in this ratio over the past two years. So viewed in the shorter-term, corporates have become more liquid following the 2008-09 recession. However, it is simplistic to argue that this indicates a growing propensity to invest. Indeed, it could be interpreted as the opposite: Perhaps corporations have been raising liquidity because they are risk-averse. Perhaps they have specific concerns, for example, that their access to bank credit might be constrained in future given the poorly capitalised financial system.

Let’s now turn to a discussion of solvency. One of the most important measures is the ratio of total debt to net worth. As this increases, leverage increases and solvency declines. Note that, in the 2008-09 recession, there was a huge rise in this ratio which, notwithstanding massive fiscal and monetary stimulus, has declined only slightly since. Other factors equal, if the economy does indeed slow over the coming quarters as the stimulus fades, this ratio is more likely to rise again than to fall, indicating worsening solvency. US corporations are already highly leveraged in a historical comparison. In a slowdown, they are likely to become involuntarily even more so. This makes it rather less likely that they are going to increase investment spending.

Meanwhile, U.S. Corporate Leverage Remains Elevated (Debt/Net Worth, %)

Source: US Federal Reserve

Were corporates to deleverage their balance sheets sufficiently such that their debt/net worth ratios were under 50%, a corporate investment-led recovery would seem rather more plausible. The fact that corporates have become somewhat more liquid would also help at the margin. But realistically, it is going to be some number of years before corporate leverage can be reduced to a level normally associated with incipient investment booms.

Finally, it is worth considering whether the general tax and regulatory environment is currently investment friendly or not. Other factors equal, rising government debts, as compared to national income, or GDP, imply higher taxes in future. After all, that debt has to be serviced. And while interest rates might currently be unusually low, it so happens that, as economic growth recovers, interest rates are going to rise. As such, governments are going to need to rely on generally higher rather than lower tax revenues for the foreseeable future.

This also helps to explain, for example, why a number of prominent US politicians are pushing for a national sales tax, or value-added-tax (VAT), as well as higher income tax rates. In general, these are sought not to finance new government programmes, rather to finance existing ones. Businesses are smart enough to know that, even if the government does not raise corporate taxes directly, it is likely to raise them indirectly, by increasing taxes on customers’ incomes and purchases.

Combined with the need for households to deleverage to a much greater extent than they have so far, the implication is that the after-tax income that households are actually likely to spend is not going to grow at a particularly strong rate in the coming years, limiting corporate revenue and profit growth.

Household Income / Net Worth Has Yet to Recover Meaningfully...

Source: US Federal Reserve

...Primarily Due to the Weak Housing Market (Homeowners' Equity, %)

Source: US Federal Reserve

Excessive Leverage + Excessive Leverage = Excessive Leverage

The maths here are not particularly complicated. Households have deleveraged slightly, as have corporations, but in both cases leverage remains well above where it was prior to the 2008-09 recession. Meanwhile, governments have assumed exponentially growing debt burdens to compensate for weak demand elsewhere. While this has helped to re-liquefy the global financial system and has no doubt supported growth in general during 2009-2011, looking forward, the outlook for consumption, investment, and therefore growth in general, is rather bleak. Governments might continue to increase spending, as they are naturally inclined to do. And central banks might continue to accommodate large government budget deficits. But be under no illusions: There is nothing sustainable about that. Indeed, it is both borrowing growth from the future and, by arbitrarily misallocating resources in the interim, reducing economies’ potential growth rates.

Returning to the topics of liquidity and solvency, investors need to understand that, in a world of unbacked fiat-currencies, there is only ever a shortage of liquidity when that becomes an explicit goal of central bank policy. As long as central banks are willing to create liquidity, liquidity there will be. But there is nothing short of large currency devaluation that central banks can do to improve solvency. The problem then becomes, if a number of financial systems are insolvent, they who is going to devalue against whom? Is it really a solution for all countries with insolvent financial systems to devalue against all others?

Quite obviously not. And history demonstrates that when a number of countries all seek to devalue against one another simultaneously, the result is some combination of trade wars or capital controls.

Corporate profit margins may seem healthy at present, but it is unlikely that they remain so for long. The squeeze is coming, from higher input/commodity prices on the one hand and household deleveraging and higher taxes on the other. In the event that trade barriers begin to rise or capital controls are imposed, highly complex modern multinationals are going to find a substantial part of their operations are no longer as profitable as they once were. This risk is not remote; it should be priced into the equity risk premium. In our view it is not.

Investors are thus faced with a financial trilemma: Cash rates are negative in real terms and currencies are at risk of devaluation; bond yields are low; and equity valuations, while more attractive now following a modest correction, incorporate neither the reality nor the risks of the overleveraged, capital misallocated world in which we live.

The best action investors can take, therefore, is to reduce holdings of financial assets across the board, in favour of real assets. With liquidity concerns still paramount amidst an overleveraged financial system, commodities, as liquid real assets, should be overweighed in a defensive investors’ portfolio. It may seem counterintuitive, as commodities, in normal economic circumstances of strong financial systems and sustainable growth, are associated with a more speculative, short-term investment approach. But when cash rates are negative and financial assets in general are overpriced, the situation becomes reversed. It is now cash, and financial assets generally, that have become speculative instruments, rather than sources of prudent investment opportunities. Liquid real assets are the best, indeed, the only option to preserve wealth when policymakers are set, knowingly or not, on destroying it instead.

[1] Please see Who Will Rescue the Rescuers, Amphora Report Vol. 2, September 2011.

[2] For a detailed discussion of debt ratios and what they portend for the future, please see Reinhart and Rogoff, This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Finally Folly. Among other observations, they point out that, historically, sovereign debt/GDP ratios in excess of 90% invariably lead to crisis, default and/or devaluation.