Researchers at the New England Complex Systems Institute (CSI) studied periods of social unrest in the Middle East and North Africa to attempt to explain the underlying causes of the riots that swept these areas in 2008 and 2011. The Cambridge-based researchers looked at a variety of factors that could trigger unrest – poverty, oppression, unemployment, etc. in an attempt to explain the disturbances.

The study found the factor most responsible for triggering riots and social unrest was rising food prices. High food prices do not trigger riots themselves according to the research, but created conditions in which social unrest could flourish.

Since the majority of the world's crude oil is produced and exported from the Middle East and North Africa – roughly one of every two barrels is exported from this region – instability in this area would create major global economic problems.

While the anti-U.S. riots in Libya, Egypt, Yemen, Iran and elsewhere in the Middle East and North Africa that broke out last month were blamed on an American-made video, the study claims that periods of social instability in this region can be accurately predicted by food prices – and the film happened to be the trigger for the unrest.

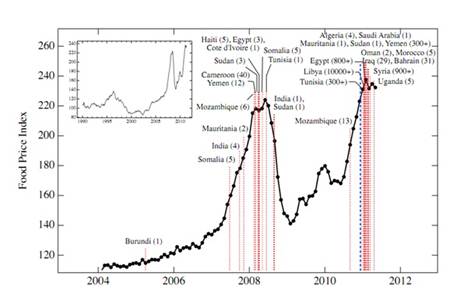

CSI Findings - Plotting global food prices, as measured using the United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO’s) Food Price Index, against the dates of recent unrest the researchers found a high degree of correlation between the high food prices and periods of instability. The chart above (from the CSI report) covers the period from January 2004 to May 2011.

When the FOA’s Food Price Index climbed above the threshold level of 210 the researchers found that conditions tend to ripen into periods of social unrest. The study doesn’t claim that a breach of the 210 level immediately leads to riots, just that the probability of instability becomes much greater.

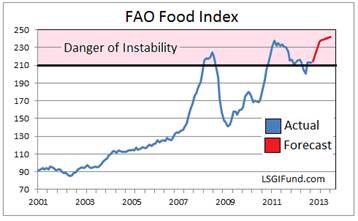

The FAO Food Price Index is at 216 in September, slightly above the instability threshold identified in the report. The FAO Index has been above the threshold level for most of the year. Going forward the price of food is expected to move upward with the drought in the U.S. and Russia adding to pricing pressures, thus increasing the probability of unrest.

For the millions of people in developing economies food comprises anywhere from 35% to 80% of routine household expenses. The Middle East and North Africa are major importers of grains and foodstuffs, so increasing food costs are quickly reflected in local prices. In the more developed economies household expenditures on food are more like 10% to 15%. High food prices have a larger and more direct impact on households in developing economies, posing a challenge for these governments.

One of the authors of the report predicted another “massive food price spike” this fall and winter, even bigger than the last one seen in 2011. This crest will be exacerbated by this summer’s drought and heat wave in many grain growing areas. He noted that “when people are unable to feed themselves and their families, widespread social disruption occurs. We are on the verge of another crisis, the third in five years, and likely to be the worst yet, capable of causing new food riots and turmoil on a par with the Arab Spring.”

Rabobank Report - World food prices are forecast to hit an all-time high in the first quarter of next year - and then keep rising - as crops in the U.S. have been hit by the country's worst drought since 1936 according to a new report issued last month by Rabobank, a financial institution specializing in agriculture economics and research.

Rabobank Report - World food prices are forecast to hit an all-time high in the first quarter of next year - and then keep rising - as crops in the U.S. have been hit by the country's worst drought since 1936 according to a new report issued last month by Rabobank, a financial institution specializing in agriculture economics and research.

Food prices, as measured by the United Nations FAO Food Price Index, could climb by 15% from current levels according to Rabobank, reaching a record 244 by July, 2013 (see chart). This price level would be well into the zone where the probability of instability in the Middle East increases substantially. The FAO index previously hit an all-time high in February, 2011, just as the ‘Arab Spring’ ignited riots across the region.

As a result of drought in key exporting countries and rapid demand growth, Rabobank forecasts the combined global wheat, rice, corn and soybean stocks-to-use ratio will fall to 19.6 per cent in 2013. In addition, export bans and commodity stockpiling by concerned governments could exacerbate commodity price volatility.

According to the report the most affected commodities are those largely used in animal feed (corn and soybeans) and are not core food staples (wheat and rice), therefore the impact of the price increases might be more severe in economies that consume high levels of meat and dairy products.

The Rabobank report also made the following points regarding the agricultural sector:

- Food security remains a highly sensitive issue in many regions. They expect to see a return of government intervention, which could exacerbate food and commodity price volatility. Increases in commodity stockpiling and other interventionist measures, such as export bans, are a distinct possibility as governments react to protect domestic consumers from increasing world food prices. Increased intervention will likely add to increasing world food prices.

At the end of August, severe or extreme drought conditions covered over 42 percent of the U.S. mainland. June to August precipitation and heat in the central U.S., where most of the U.S. row crops are produced, is likely to result in the least favorable growing conditions since the Dust Bowl (1936).

At the end of August, severe or extreme drought conditions covered over 42 percent of the U.S. mainland. June to August precipitation and heat in the central U.S., where most of the U.S. row crops are produced, is likely to result in the least favorable growing conditions since the Dust Bowl (1936).- The scale of the production setbacks this season will underscore the need for an almost unprecedented amount of demand rationing. Rabobank’s crop modeling indicates that there may still be a considerable downside from current official production forecasts. Fundamentals remain much tighter than current official market estimates.

- The price of energy and agricultural products have correlated very closely over the last decade. The increasing production of biofuels has been one reason for this high degree of correlation, as well as the upgrading of diets and lifestyles in China and other developing countries.

- With regard to China, the Financial Times pointed out last month that China’s corn imports are going through the roof – and are expected to stay elevated for quite some time. The increase in demand, and extended drought, should help put a floor under any price weakness. The Financial Times chart at right is stunning.

Iran Embargo – In addition to the potential unrest in the Middle East triggered by rising food prices, rising tensions between Israel and Iran could drive oil prices above $130 a barrel next year according to a new report by Goldman Sachs. They see the embargo taking a large share of Iran’s production off the market for an extended period of time, which should keep oil prices elevated.

Separately, Robert McNally, the former chief energy advisor on President George W. Bush’s National Security Council, sees a “dangerous divergence” between market players and policy makers with regard to the risks of a conflict between Israel and Iran. McNally says the markets appear to assign only a 5 per cent probability of an escalation in the conflict, whereas policy makers “are more like 50-50 right now.” He went on to note he has never seen a gap in probabilities so large. Oil prices should move upward as the market becomes more aware of the risks.

Portfolio Implications – If the studies noted above are correct, rising food prices will likely generate more instability in crude oil exporting countries. The Iran/Israel conflict and ongoing embargo should also take crude oil supplies off the market. In such an environment proven oil reserves in politically secure areas of the globe should increase in value. We can buy these reserves at a steep discount in today’s equity market.