The U.S. Shale Oil Boom

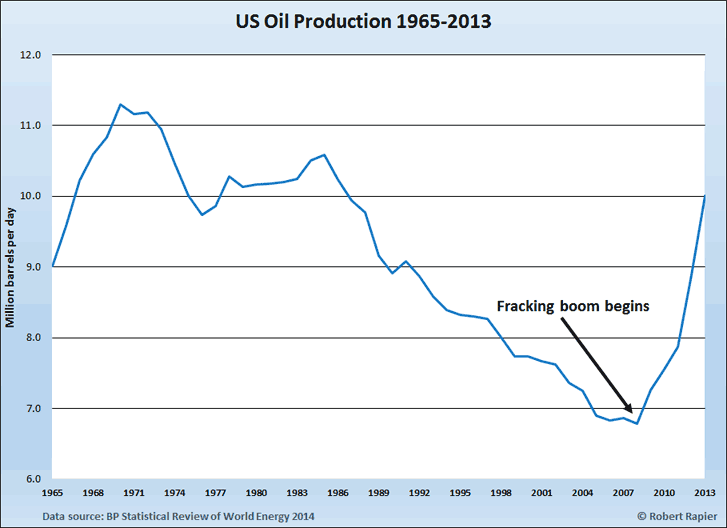

There have been a lot of stories over the past few years about the implications of the U.S. shale boom. To review for those who might have been living in a cave for the past 5 years, the marriage of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (fracking) has reversed 40 years of declining U.S. oil production and created a shale oil and gas boom.

As amazing as it would have seemed a decade ago, U.S. oil production is increasing at the fastest pace in U.S. history. In the past 5 years U.S. oil production has increased by 3.22 million barrels per day (bpd). The overall global oil production increase during that time was only 3.85 million bpd, meaning the U.S. was responsible for 83.6 percent of the total global increase over the past 5 years.

This resurgence in U.S. oil production has had a number of implications. One has been that U.S. oil imports have declined. Thus, even though the U.S. has an oil export ban in place (which has had the impact of discounting U.S. crude relative to globally traded crudes), global oil supplies have nevertheless increased as oil exporters sought other outlets to replace the declining U.S. business. This has weakened the pricing power of OPEC.

Shale Oil Economics

The shale boom was enabled by high oil prices. The cost of production for shale oil is higher than for most onshore conventional oil, and therefore high prices were needed to encourage shale oil production. How high? Estimates vary, but a couple of years ago the marginal cost for shale oil was estimated to be around 0/bbl. That cost has been declining as drillers implemented improvements like multi-pad drilling, and today is probably ~/bbl. With the price of West Texas Intermediate hovering around /bbl, the market price of crude oil in the productive shale regions has slipped below /bbl (due to the need to transport it to market, it generally trades at a discount to WTI).

What does this mean? If the price of oil falls below the break even level for an extended period of time, marginal producers will begin shutting down and lower cost producers will likely reduce their spending on new exploration and drilling. The current expansion of U.S. oil production would then stall sooner than expected.

Who would benefit if this happened? In the long run, Saudi Arabia, other OPEC producers, and Russia. The world’s other major oil producers have watched U.S. oil production grow, and it looks like they might finally be ready to do something about it.

Saudi’s Three Options

When you think about it from Saudi Arabia’s perspective, they have three choices. They can choose to do nothing, in which case oil prices might weaken as long as long as U.S. production continues to grow. At the rate the U.S. is going, we threaten to overtake Saudi Arabia as the world’s largest oil producer within the next few years ago. A few years ago I would have been incredulous at this notion, but at this point I can’t say that’s impossible.

Saudi can also convince OPEC producers to cut production in order to support current oil prices. This will force them to give up some revenue, but again, if U.S. oil production continues to increase OPEC may be forced to keep cutting oil production for the next few years in order to maintain global oil prices. As with the previous option, this benefits U.S. oil producers.

Their third option does not benefit U.S. oil producers. Saudi could attempt to reduce the price of oil until shale oil production starts to become uneconomic. Saudi Arabia has been accused of using oil in the past as an economic weapon. In the present case, it would mean short term pain for OPEC, but if they can stop the momentum of the shale oil boom then OPEC would regain some of its pricing power. Saudi Arabia reportedly needs oil prices between and /bbl to balance its budget, and if they can short-circuit the U.S. shale boom they will have more influence in ensuring they can set the price where they want.

This third option looks increasingly like Saudi Arabia’s strategy. Reuters reported this week that Saudi Arabia has been quietly telling the oil market that it would accept oil prices as low as for up to two years. If this is the case, and Saudi Arabia manages to hold oil prices at , the result may be lower U.S. oil production in future years than would have otherwise been the case. Saudi Arabia would once more be entrenched as the most powerful country when it comes to setting the price of oil.

Conclusions

As I have argued in the past, I view it as a serious national security concern when a country could bring the U.S. economy to its knees overnight. Saudi Arabia still wields significant pricing power, but that power has weakened in recent years. If they win a price war with U.S. shale oil producers, consumers will benefit at the pump while the war wages, but at a cost of putting more long-term pricing power in the hands of Saudi Arabia.

Whether we do it with increased oil production, lower oil consumption through higher fuel efficiency and alternative energy – or some combination, we need to make sure our energy policies do not put the future of the U.S. economy back in the hands of countries that do not have the best interests of the U.S. at heart. For some additional perspective on this issue, see my colleague Jennifer Warren’s article The OPEC Oil Market Gambit.