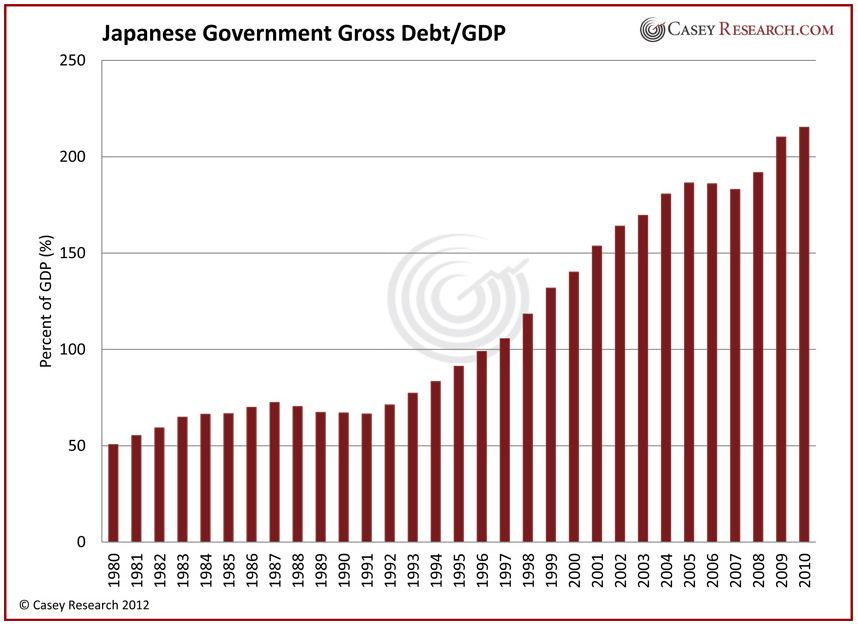

On the heels of Fitch's sovereign credit downgrade to A plus (the fifth-highest investment grade), Japan's government debt continues to swell. With its debt at over 200% of its GDP, the Land of the Rising Sun appears to be embarking on a trek into the debt-laden unknown.

(Click on image to enlarge)

A ballooning government debt is often associated with sovereign debt crises, as market shocks can send the interest rate paid on the debt to unsustainable levels. Coupled with Japan's shrinking population (and thus tax base), the country is setting itself up for a hairy situation (data for both charts are from the IMF's World Economic Outlook Database).

(Click on image to enlarge)

As with any well-known macro-trend, there are speculators eager to capitalize on it.

Enter Kyle Bass, one of the few hedge fund managers who made a killing when he bet against housing during the subprime mortgage bust. He and his fund have now set their sights on Japan, specifically shorting Japanese yen and Japanese government debt.

His thesis is simple: with a debt-to-GDP ratio over 200% and a contracting population, it's only a matter of time before a sovereign debt crisis sets in, thus triggering a rise in Japanese interest rates – which the government would be unable to service with a shrinking and aging tax base.

So far this strategy hasn't worked as Bass intended: according to ValueWalk, Bass' fund lost 29% of its value in April alone.

That's not to say Bass' assumptions are incorrect. But there are alternative ways of looking at Japan's situation.

Many blame the 2011 earthquake and subsequent reconstruction efforts for the ballooning debt, while some, like Business Insider columnist Joe Weisenthal, think Japan will never implode.

Weisenthal's main point is that Bass' analysis is simplistic and incorrect. He says that the debt-to-GDP ratio is a lousy measure of anything because "it's measuring a stock (total debt) to a flow (a country's national income for the year)." And "beyond that, debt-to-GDP just doesn't tell you anything about interest rate risk or credit risk."

Weisenthal is entitled to his opinion, but we think Bass will eventually be proven right – although his fund could go broke in the meantime.

The Japanese problem is real, and a sovereign default – outright or inflationary – along with the rising rates that lead up to it are inevitable. But as we have said many times before, just because something is inevitable doesn't make it imminent.

Recognizing the development of a new trend – such as a nascent sovereign debt crisis – is only half of a successful investment. The other half, as Bass demonstrates so well, is timing. Even though the US appears to be losing the debt-default race so far, that could change at any moment – and with a presidential election on the horizon, change could be imminent. Fortunately, there are steps an investor can take today to not just avoid that pain, but be poised to profit.