The United States is quickly coming to resemble a post industrial neo-3rd-world country. Unemployment, lack of economic opportunity, falling real wages and household incomes, growing poverty and increasing concentration of wealth are major trends in the U.S. today. Behind these growing problems are monetary inflation created by the Federal Reserve’s monetary policies, federal government deficit spending and the dominant influence of “too big to fail” banks and large corporations in Washington D.C., which has altered the direction of law in the United States. To make matters worse, the U.S. government faces a historic fiscal crisis.

Photograph courtesy of Mitch Cope

High unemployment, lack of economic opportunity, low wages, widespread poverty, extreme concentration of wealth, unsustainable government debt, control of the government by international banks and multinational corporations, weak rule of law and counterproductive policies are defining characteristics of 3rd world countries. Other factors include poor public health, nutrition and education, as well as lack of infrastructure—factors that deteriorate rapidly in a failing economy.

Apparently ineffective regulation and relatively little law enforcement action by the federal government in the wake of the sub-prime mortgage meltdown resulted in widespread speculation that special interests had taken priority over the rule of law. Critics have also charged that the federal government’s policies threaten to eliminate what remains of the American middle class.

Accelerating Concentration of Wealth

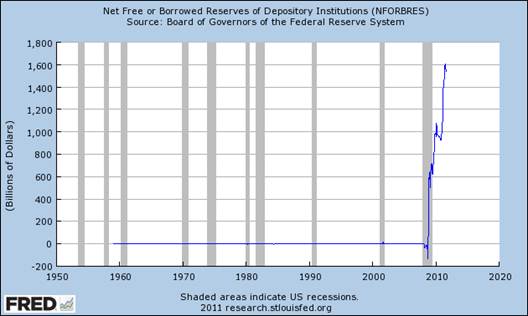

In response to the economic downturn that began in 2007 and the start of the financial crisis in 2008, the U.S. federal government and the Federal Reserve resorted to a radically inflationary policy intended to save banks and to shepherd the U.S. economy through a recession. Instead, radically inflationary policies greatly increased the concentration of wealth.

Under ordinary circumstances, monetary inflation has the effect of redistributing wealth in favor of those who receive newly created money first. The value of money is reduced as a function of the number of currency units in the economy but recipients of newly created money can spend it before it loses value. In a declining economy, however, the wealth redistribution effects of inflation are magnified.

When the Federal Reserve or the federal government supports banks and financial markets through liquidity injections, bailouts, asset purchases, quantitative easing, etc., the lion’s share of financial support, i.e., newly created money, is captured by the largest financial institutions and by the wealthiest 1% of Americans. Money printing skews the distribution of money over the economy while the value of money, i.e., the purchasing power of wages and savings, is reduced. The overall effect is a wealth transfer from proverbial Main Street to literal Wall Street.

Looming Fiscal Crisis

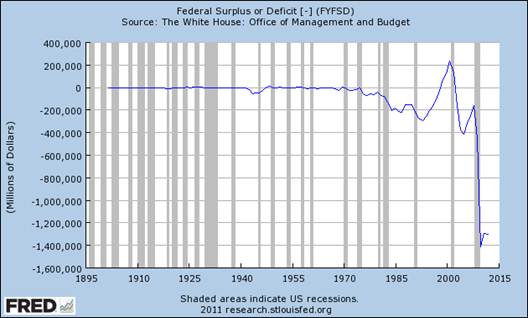

U.S. government debt and deficit spending have markedly accelerated over the past decade. For example, The U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) was created and the U.S. military grew to 3 million active duty and reserve personnel, not including contractors. Since 2001, the U.S. spent approximately trillion on military expansion while the total cost of the U.S. wars in Afghanistan and Iraq has been estimated to exceed .7 trillion.

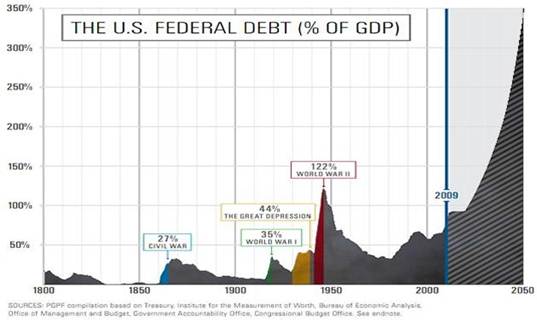

Although the U.S. federal government remains in denial, the Congressional debt ceiling debate and subsequent U.S. credit rating downgrade on August 5, 2011 were only the tip of the iceberg. In fact, the United States faces a historic fiscal crisis.

As of 2012, the majority of new federal government debt will stem from interest on existing debt. Treasury bond issues totaled .55 trillion in 2010, roughly 2x the federal budget deficit of .3 trillion. Artificially low U.S. Treasury bond yields, created by the Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing (QE1 and QE2) programs and by its current “Operation Twist,” only slow the rate at which the federal debt balloons.

The U.S. federal government’s fast growing debt is .94 trillion, approximately 100% of GDP. Additionally, future liabilities total .6 trillion based on generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP accounting) and using official data from the Medicare and Social Security annual reports and from the audited financial report of the federal government.

- Medicare: .8 trillion

- Social Security: .4 trillion

- Federal debt: .2 trillion* (not including intra-governmental obligations)

- State, local government obligations: .2 trillion

- Military retirement/disability benefits: .6 trillion

- Federal employee retirement benefits: trillion

The eventual insolvency of the U.S. federal government cannot be averted through any combination of taxes, budget cuts or realistic GDP growth. Inflationary policies, i.e., increasing deficit spending by the federal government and debt monetization by the Federal Reserve, would devalue the U.S. dollar and potentially trigger a hyperinflationary collapse of the currency. To stave off the inevitable, interim measures might include tax increases, exchange controls, nationalization of pension funds or other measures similar to those taken in 3rd world countries.

Dominant Corporate Influence

In a 2009 radio interview on Elmhurst, Illinois’ WJJG 1530 AM, Senator Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) explained that “…the banks—hard to believe in a time when we’re facing a banking crisis that many of the banks created—are still the most powerful lobby on Capitol Hill. And they frankly own the place.” Senator Durbin was unequivocal in saying that the federal government of the United States is controlled by banks. Simon Johnson, former chief economist of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), had reached the same conclusion one month earlier in his widely read article The Quiet Coup. Johnson explained that the finance industry had effectively captured the U.S. government, a state of affairs typical of 3rd world countries.

Corporate influence over the political process, as well as over the tax and regulatory policies of the United States, is at an all time high. The federal government is the largest single customer in the U.S. economy and, through taxation or regulation, the government can grant or deny market access to private companies and can either prevent or mandate the consumption of their products and services. As a result, virtually every large corporation in the United States seeks to win the government’s business and to steer government tax policies and regulations in their favor. Naturally, politicians who accede to the wishes of particular corporations are given campaign funds to ensure their reelection. In the past decade, the amount of money spent on lobbying has more than doubled and there are currently 24 lobbyists for every 1 member of Congress.

The interdependence of elected officials and the largest U.S. corporations reached a new high with the 2008 bank bailouts. The influence of private corporations and de facto industrial cartels (comprising the largest corporations in each major industry) over tax and regulatory policies creates significant economic distortions that ultimately compromise the sustainability and the stability of the economy. Ideally, the government would be an impartial referee, rather than an active business partner that overwhelmingly favors large businesses over small businesses, despite the fact that small businesses account for the vast majority of American jobs.

Impact on the Rule of Law

Corruption, cronyism and weak rule of law are typical of 3rd world countries. The United States exhibits a clear corporate influence over elections and legislation and, arguably, relatively little law enforcement action where large, legally well-equipped corporations are concerned. Reports of so-called crony capitalism have appeared in the U.S. news media, but the term “corruption” has been avoided, along with discussion of fundamental reforms.

A cursory examination of legal developments over roughly the past decade evidences a pattern in which U.S. federal law systematically favors the largest financial institutions, as well as a paradigm in which financial institutions heavily influence both the regulations that putatively govern their activities and the laws that apply to consumers of their products and services. The financial crisis that began in 2008 and the subsequent response of the federal government appear to follow logically from prior legislative events:

- 1999 Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act (GLB). The Act repealed key provisions of the Banking Act of 1933, commonly known as the Glass–Steagall Act. In the aftermath of the Great Depression, the Glass–Steagall Act prevented depository institutions from engaging in high risk financial speculation.

- 2000 The Commodity Futures Modernization Act (CFMA). The Act deregulated over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives, such as credit default swaps, referred to by Warren Buffett as “financial weapons of mass destruction.” OTC derivatives were at the heart of the financial crisis that began in 2008 and are the root cause of the “too big to fail” doctrine. The Act preempted state gaming laws that had prevented banks from speculating in OTC derivatives with no connection to underlying assets.

- 2001 USA PATRIOT Act. The financial provisions of the Act allow banks to collect additional financial information about account holders, for example, linking business accounts to the personal financial records of business owners, thus weakening both financial privacy and the corporate veil. The Act enhances the ability of creditors to collect and allows federal authorities to monitor financial transactions and to obtain financial records without a subpoena.

- 2005 Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act (BAPCPA). The Act, which was sponsored by banks and credit card companies, effectively eliminated the concept of a “fresh start” by allowing banks and credit card companies to engage in collections activities, in effect, forever. As a result, small business owners who end in bankruptcy are less likely to ever start another business. The Act places banks in front of bankruptcy courts, creates liabilities for bankruptcy attorneys and contains many widely criticized, anti-consumer provisions.

- 2008 Emergency Economic Stabilization Act. The Act, commonly referred to as a “bank bailout,” authorized the United States Secretary of the Treasury to spend 0 billion to purchase distressed assets, especially mortgage-backed securities (MBS). Instead, the funds were given to foreign and domestic banks to offset their risky MBS, OTC derivatives and other losses. The bank bailout set a precedent of socializing losses but keeping gains private. The Act effectively bound the fate of the U.S. Treasury to that of the largest U.S. financial institutions.

- 2010 Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission. The Supreme Court of the United States held that corporate funding of independent political broadcasts in candidate elections cannot be limited under the First Amendment, overruling prior case law and guaranteeing the ability of corporations to influence elections without meaningful restrictions. The Court’s decision gave carte blanche to corporations to influence elections, legitimized the interdependence of elected officials and large corporations and created a precedent under which the rights of corporations supersede those of citizens.

- 2010 The Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. The Act failed to restore critical provisions of the Glass–Steagall Act, significantly regulate OTC derivatives, break up “too big to fail” banks, prevent another financial crisis and prevent further bailouts. The Act created a Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, but did not repeal any provision of BAPCPA or restore the financial privacy of U.S. citizens removed by the USA PATRIOT Act. The Act failed to provide adequate funding to the government’s watchdogs, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), potentially hobbling enforcement. The Act has also been criticized for the burden it places on smaller competitors in the financial sector, which could ultimately result in an increased concentration of financial power in “too big to fail” banks.

Critics have alleged that, underlying the sub-prime mortgage meltdown that triggered the financial crisis in 2008 was rampant fraud. Fraud has been alleged at virtually every level from the assessment of property values and credit risk; to the loans themselves and to their securitization as MBS assets; to the ratings of MBS assets as AAA; to hedging or betting against MBS assets in the OTC derivatives market (perhaps including financial firms allegedly betting against MBS assets that they themselves created and sold to clients as AAA assets). After the crisis, a seeming pattern of fraud continued apparently unabated in the robo-signing foreclosure scandal where documents submitted to courts were falsified. Despite an avalanche of alleged crimes under existing federal law, no firm or individual of any significance in the financial crisis has yet been prosecuted.

President Barack Obama said in October 2011 that the mortgage finance practices leading to the economic meltdown were “immoral, inappropriate and reckless … but not necessarily illegal.” Since fraud is, in fact, illegal, critics claim that the U.S. federal government has simply failed to enforce the law. Adding fuel to the fire, the Solyndra loan scandal could be construed to suggest corruption at high levels and the MF Global debacle could be construed as indicative of weak regulation and law enforcement and even of questionable market integrity.

In theory, selective enforcement of the law risks the creation of two sets of laws: one for big banks and corporations, and for their executives, i.e., those with connections in Washington D.C. or on Wall Street, and one for everyone else. Among other things, failure to enforce the law could create an environment in which crime pays, but, for ordinary citizens, hard work, prudent financial decision making, saving and investing for the long term do not.

More than any other aspect of America’s progression towards 3rd world status, the federal government’s low level of law enforcement action where “too big to fail” banks are concerned is perhaps the most insidious because it raises questions of legitimacy and of the social contract. A financial and legal system of moral hazard implies that victims face double jeopardy while they are deprived of legal recourse, i.e., those allegedly defrauded might face inflation and tax burdens stemming from preferential treatment of favored corporations or from further bailouts.

Destructive Tax Policies

In the face of rising government debt, the rapidly shrinking American middle class is the primary target of the U.S. federal government’s tax policies. The eventual extinction of the American middle class would be a key milestone along the road to 3rd world status. Current U.S. tax policies favor the largest corporations and this is unlikely to change in the foreseeable future. Although tax increases exacerbate economic downturns, several tax options have been or are being discussed. However, none of them are likely to be put in place.

- Increasing taxes on corporate profits would result in job losses in the short term and would affect dividends and share prices in the stock market. Lower dividends or share prices would affect pension funds, including government pension funds.

- Increasing taxes on capital gains would impact the non-tax-exempt investments of the now retiring “baby boomer” generation and would reduce capital formation thus reducing investment in new businesses or business expansion and hampering job growth.

- Increasing payroll taxes would cause companies to downsize resulting in job losses and would have a chilling effect on hiring.

- A Value Added Tax (VAT) is impractical in the United States because countless special taxes already exist at all levels of the supply chain. To prevent unpredictable, disruptive consequences, implementing a VAT would require years of study and comprehensive tax reform.

- A national sales tax is undesirable because it would overlap and interfere with already existing state sales taxes, which are highly inconsistent across states.

- Carbon taxes remain possible but they would encumber businesses and result in job losses or reduce hiring.

Chief among the remaining possibilities is the income tax but, according to the Tax Policy center at the Urban Institute, Brookings Institution, 46% of American households will pay no federal income tax in 2011. The reasons include income tax exemptions for subsistence level income, dependents and nontaxable tax expenditures for senior citizens and low-income working families with children.

Assuming that big banks, multinational corporations and the wealthiest 1% of Americans remain off limits in terms of tax policy, the range of income taxed is likely to widen from the current tax on households earning more than $250,000 per year to progressively lower income levels. In fact, the government’s intended revenue source is precisely what remains of the once much larger middle class: professionals, small business owners and dual income families in urban areas, etc. These are the households that have managed to stay ahead of inflation, declining real wages and falling household incomes.

Among other things, U.S. tax policies will erode capital formation within the remnants of the middle class, which is the engine of small business creation and the source of most American jobs. The eventual result will be a three-tier socioeconomic structure consisting of a super rich wealthy class, a much poorer working class and a massive, politically and financially disenfranchised underclass, similar to that of a 3rd world country.

Via Dolorosa

The United States increasingly resembles a 3rd world country in terms of unemployment, lack of economic opportunity, falling wages, growing poverty and concentration of wealth, government debt, corporate influence over government and weakening rule of law. Federal Reserve monetary policies and federal government economic, regulatory and tax policies seem to favor the largest banks and corporations over the interests of small businesses or of the general population. The potential elimination of the middle class could reshape the socioeconomic strata of American society in the image of a 3rd world country. It seems only a matter of time before the devolution of the United States becomes more visible. As the U.S. economy continues to decline, public health, nutrition and education, as well as the country’s infrastructure, will visibly deteriorate. There is little evidence of political will or leadership for fundamental reforms. All other things being equal, the U.S. will become a post industrial neo-3rd-world country by 2032.