It seems as though each passing day brings yet another piece of bad economic news coming out of Venezuela. For months, I have been tracking the decline of Venezuela’s economy and its currency, the bolivar. As if a collapsing currency, and the resulting inflation and empty shelves weren’t bad enough, Venezuela is now struggling with massive blackouts. Forget the Whig interpretation of history; Venezuela supports the schoolboys’ interpretation: “it’s just one damn thing after another.”

Venezuela’s downward economic spiral began in earnest when Hugo Chavez imposed his “unique” brand of socialism on Venezuela. For years, the country has sustained a massive social spending program, combined with costly price and labor-market controls, as well as an aggressive foreign aid strategy. This fiscal house of cards has been kept afloat—barely—by oil revenues.

But, as the price tag of the regime has grown, the country has dipped more and more into the coffers of its state-owned oil company, PDVSA, and (increasingly) relied on the country’s central bank to fill the fiscal gap. This has resulted in a steady decline in the bolivar’s value – a decline that only accelerated as news of Chavez’s failing health began to emerge.

Hugo Chavez died on March 5, 2013 – sending shockwaves through the Venezuelan economy. Not surprisingly, in the months since his hand-picked successor, Nicolas Maduro, took the reins as Venezuela’s new president, the Venezuelan house of cards has begun to collapse.

The black market exchange rate between the bolivar (VEF) and the U.S. dollar (USD) tells the tale. Indeed, the bolivar has lost 64.5% of its value on the black market since Chavez’s death (see the accompanying chart).

This, in turn, has brought about very high inflation in Venezuela. At present, the implied annual inflation rate is actually in the triple digits, coming in at a whopping 297% (see the accompanying chart).

This rate is over five times higher than the most recent official annual inflation rate of 54% reported by the government and echoed by the international financial press. Indeed, as I read in the Financial Times (9 December 2013), the figure “54%” stares me in the face. Why? The answer is straightforward: the Venezuelan censors are effective. Perhaps not as effective as the Chinese censors. But, effective nevertheless. The Caracas-based reporters I speak to regularly tell me that the news organizations actually do most of the work themselves – self censorship – to avoid having their reporters in Caracas being given the boot.

The government has responded to its economic woes by imposing ever-tougher price controls to artificially suppress inflation. But, these policies are nothing new. For years, the government has set the price for a number of goods. For example, premium gasoline is fixed at only 5.8 U.S. cents per gallon – that’s cheaper than a gallon of potable water in Caracas.

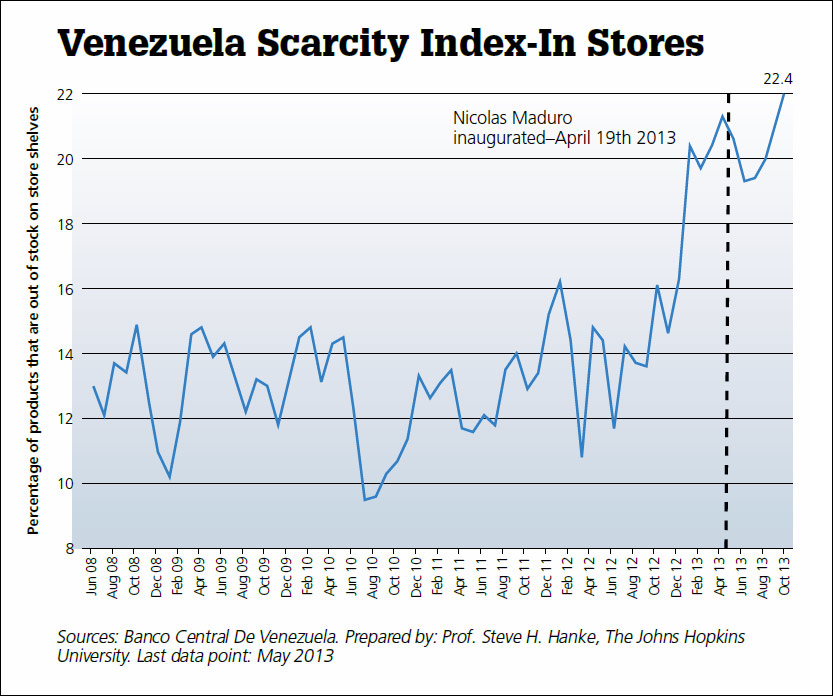

While these controls ostensibly keep prices on official markets low, they have ultimately led to empty shelves. Indeed, as the accompanying chart shows, approximately 22.4% of goods are simply not available in Venezuelan stores. This index should remind everyone of the Paul McCartney classic, “Back in the USSR.”

In addition to scarcity, price controls can lead to unintended political consequences down the road. For example, once price controls are implemented, it is very difficult to remove them without generating popular unrest – just consider the 1989 riots in Venezuela when President Carlos Perez attempted to remove price controls.

Recently, in a panicked, misguided response to the country’s economic problems, Maduro sought, and was granted, emergency powers over the economy. His first move was to set a cap on corporate profits, although this is somewhat of a diversionary tactic, since inflation eats away at corporate profits and return on investment.

Maduro has also taken aim at the auto industry, signing a decree to regulate car production “from the factory door to the place of sale”. In consequence, the government has begun to fix prices for cars and crack down on those who sell at market prices. It will be interesting to see who Maduro blames when this results in a shortage of new cars.

This choice between “fair” prices and arrest is now the norm for business owners in Venezuela. The most outrageous instance of this took place in early November, when government security forces occupied local electronics stores and began handing out TVs and other wares at “fair” (read: rock-bottom) prices. Hebert Garcia, head of the High Commission for the People’s Defense of the Economy, put it bluntly: “We have to guarantee that everybody has a plasma television and the latest-generation fridge.”

Not surprisingly, the masses lined up around the block for their piece of the government’s action. Too bad the government has failed to provide enough electricity to power the plunder. In most countries, this would be called government theft. But, under Maduro’s reign of Marxism, this redistribution has become business as usual.

Despite frequent references to the late Hugo Chavez’s “Bolivarian” revolution, the Maduro playbook is nothing more than a rehashing of Marx and Engels’ ten-point plan. This was laid out in the Communist Manifesto – a crystal-clear road map of where they wanted to take their adherents. Once you reflect on the Manifesto’s ten-point plan, you realize that Maduro (and many other politicians elsewhere) aren’t very original.

- Abolition of property in land and application of all rents of land to public purposes.

- A heavy progressive or graduated income tax.

- Abolition of all right of inheritance.

- Confiscation of the property of all emigrants and rebels.

- Centralization of credit in the hands of the state, by means of a national bank with state capital and an exclusive monopoly.

- Centralization of the means of communication and transport in the hands of the state.

- Extension of factories and instruments of production owned by the state; the bringing into cultivation of waste lands, and the improvement of the soil generally in accordance with a common plan.

- Equal obligation of all to work. Establishment of industrial armies, especially for agriculture.

- Combination of agriculture with manufacturing industries; gradual abolition of the distinction between town and country, by a more equable distribution of the population over the country.

- Free education for all children in public schools. Abolition of child factory labor in its present form. Combination of education with industrial production, etc.

The results of these Manifesto-like policies are clear. The World Bank ranked Venezuela a dismal 181 out of 189 in its 2014 “Doing Business” rankings. This puts Venezuela well behind such war-torn nations as Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

While Maduro may think of himself as modern-day Robin Hood, he has a lot more in common with Edward John Smith, captain of the RMS Titanic. That said, the economic misery created by adherence to the Communist Manifesto can take a long time to sink a ship (think USSR).

If you have doubts, just reflect on the continued popular support for the Maduro regime. On the first weekend of December, Venezuela held elections for 337 mayoral contests, and Maduro’s ruling socialist party (PSUV) trounced the opposition. Maduro came away from these victories stating that his “economic offensive” against private businesses would continue and that “We’re going in with guns blazing, so watch out.”

Sadly, even with triple digit inflation, Maduro may be right. After all, Slobodan Milosevic in Yugoslavia embraced the Manifesto, and it resulted in hyperinflation – which peaked at 313,000,000% per month in January 1994. And Slobo held on until 2000. Then there is Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe. He’s been around for 33 years, even though his adherence to the Manifesto’s mandates generated the second-highest hyperinflation in the world – peaking at 98% per day in November 2008.

So, don’t hold your breath waiting for an uprising in Venezuela because of high inflation and economic misery. Short of per barrel oil, the Titanic called Venezuela might stay afloat for longer than you think, before it inevitably sinks.

Steve H. Hanke is Professor of Applied Economics at the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, MD. He is also a Senior Fellow and Director of the Troubled Currencies Project at the Cato Institute in Washington, D.C. You can follow him on Twitter: @Steve_Hanke