There was yet another European Union summit at the end of June, which (like all the others) was little more than bluff. Read the official communiqué and you will discover that there were some fine words and intentions, but not a lot actually happened. However, there are some differences when compared with past meetings that need explaining:

There was yet another European Union summit at the end of June, which (like all the others) was little more than bluff. Read the official communiqué and you will discover that there were some fine words and intentions, but not a lot actually happened. However, there are some differences when compared with past meetings that need explaining:

- The European Council is being asked to consider permitting the European Central Bank to have a regulatory role alongside national central banks “as a matter of urgency by the end of 2012.” When this new super-regulator is eventually established, perhaps the ECB might be able to recapitalize banks directly. This was needed three years ago; the Eurozone will be lucky not to have a new banking crisis in the next few months, let alone by the year-end.

- A bail-out for Spain’s banks is agreed in principle, but it is to be funded by the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) until the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) is up and running. The EFSF has no money and relies on drawing down funds from all member states including Greece, Spain, Italy, Ireland, and Portugal, and the chances of the ESM being ratified by the individual Eurozone parliaments is very slim. We are told that Spain’s banks need about €100bn, but how much they really need is not known.

- The ESM will not rank as a prior creditor to the disadvantage of bond holders. This is a positive step, but makes it more difficult for national parliaments to authorize the ESM.

The big news in this is the implication the ECB will, in time, be able to stand behind the Eurozone banks because it will accept responsibility for them. This is probably why the markets rallied on the announcement, but it turned out to be another dead cat lacking the elastic potential energy necessary to bounce.

It was, however, the first Eurozone summit for France’s new President, Hollande. He was elected on a far-left socialist ticket, which has job protection as its top priority. Hollande and Chancellor Merkel disagree about this, with Merkel looking to eventually get some of her electors’ money back.

Hollande has already implemented some economically destructive policies for France, but this is because politics in a planned economy are always more important than economics -- until reality intervenes. On this basis, reducing the retirement age from 62 to 60 is justified, as are taxes (on property inheritance and income) that could not have been better planned to drive out the rich. The proposal to introduce a Tobin tax on bank transactions -- which was also his predecessor Sarkozy’s objective -- becomes the right thing to do, in spite of the fact that all transactions will simply be enacted elsewhere, costing jobs in Paris’ banking community. Hollande’s call for the issuance of Eurozone bonds backed by every government in the Eurozone is merely politicking, because the reality is that few outside the Eurozone will buy them. It is not just Hollande; the refusal of politicians around the Eurozone to really cut government spending has its roots in a common destructive policy of intervention that has led the Eurozone into such misery. Politicians are now helpless in the face of the crisis for which they are responsible, and they can only fall back on policies of yet more spending and economic destruction. Instead of seeking to understand market reactions through the application of economic logic based on reality, they blame markets for not buying into their crackpot schemes. And every Eurozone summit succeeds in exposing this truism to an increasingly skeptical world.

Meanwhile, Germany, meant to be the back-stop for this lunacy, is losing patience. It has become clear that the agreements that arose out of the June summit were not agreements at all. Chancellor Merkel only agreed to things she knew would not be ratified by the German political establishment. Even the German President, Joachim Gauck, in a TV interview on July 7th, took the extreme step of calling for Merkel to justify staying in the euro and to explain why it is vital for Germany to save it at great and increasing expense to taxpayers.

At the same time, nothing is being done to stem the capital flows into Germany from Greece, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Cyprus, and Ireland -- capital flows that starve the banks of deposits and increase the likelihood of banking failures in those countries.

The short-term solution to this and other pressing problems has been for the ECB to ease monetary policy further. It reduced interest rates on July 5th. You might as well play tennis with a feather duster, because a notional reduction of borrowing costs by 25 basis points for banks in the stricken countries solves nothing.

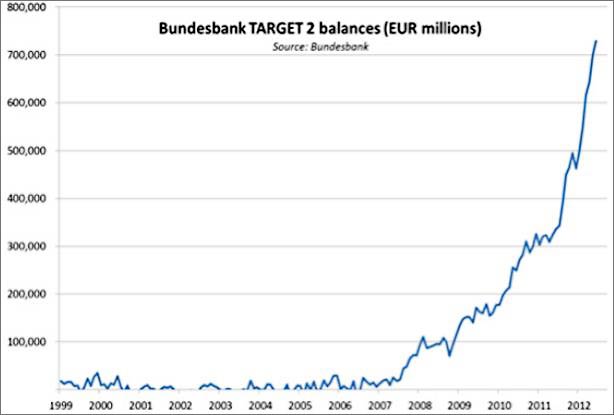

Meanwhile capital flight, as people try to find some protection, still accumulates in the stronger countries, particularly Germany. This is reflected in TARGET 2 balances, which, for the Bundesbank, is shown in the chart above. TARGET 2 is the cross-border Eurozone settlement system for larger transactions, and reflects the net difference between cross-border imports, exports, and capital flows. In normal circumstances, capital flows can be expected to balance trade flows, and this was true until July 2007; since then, there has been an acceleration of capital leaving the periphery countries. The balance at the Bundesbank as of end-June was €729bn, which is going for a trillion dollars and does not include the accumulation of savings in Germany from other Eurozone residents.

Current State of Bail-Outs

Just to recap, there are now five countries that have sought bail-outs. They are Ireland, Greece, Portugal, Spain, and Cyprus. To this must be added Italy and Slovenia, both of which are in difficulty. The problem is made more acute because they have all committed themselves to guaranteeing the funding of the EFSF (the ESM does not yet exist but is expected to do so eventually on a similar basis), meaning that they have to contribute to their own bailouts or request a suspension of their commitments from the other guarantors. Ireland, for instance, decided to raid state pension funds to meet her contribution in her own bail-out.

The EFSF guarantees are shown in the following table.

The countries that have been given bailouts are Ireland, Portugal, and Greece, for totals of €17.7bn, €26bn and €179.6bn respectively, including pending disbursements. Think of the effect on other countries in trouble having to raise funds in the bond markets: Spain has had to contribute or commit €26.5bn, which it currently has to fund at 7% and lend to these three countries at about 3.5%. This is over one quarter of the bail-out Spain is seeking for her own banks.

This is obviously crazy.

If we look at the guarantees of all those who are receiving bail-outs, requesting one, or are likely to need one, they total 41% of the fund. This eventually has to be covered by the other guarantors, principally Germany, France, and the Netherlands. While it would be a mistake to underestimate the political tensions this causes in these states, these countries are at least committed to the European cause, and we can assume their politicians will continue to fight to support the Eurozone’s objectives and institutions for as long as possible. A rebellion is more likely to come from elsewhere.

There is less drive behind paying for the status quo in the smaller nations, such as Slovakia, who are relatively new to the European Ideal. While Slovakia is unlikely to make too much fuss, the same cannot be said of Finland, who offers the greatest danger of an exit altogether. She has been sufficiently worried about previous bail-outs to independently seek preferential terms from the recipients. In her alliances, Finland regards herself as Scandinavian first and European second. The other Scandinavians are not in the currency union, and the richest state, Norway, is not even in the EU. Denmark manages its currency to maintain an approximate rate against the euro, so why cannot Finland do the same, without all the liabilities?

Increasingly, public opinion in Finland is that membership of the Eurozone is becoming an unjustifiable burden. The country lacks the historical imperative to pursue European integration and is far more likely to be the first to leave the Eurozone than other candidates frequently mentioned, particularly Germany.

The questions arises: How can the Eurozone stay together, and if not, how quickly is it likely to start disintegrating? And where does the exchange rate for the euro fit in all this?

We address these and other related topics in Part II: The Consequences of a Eurozone Breakup.

Click here to access Part II of this report (free executive summary; paid enrollment required for full access).