Bailouts appear to be the established substitute for sustainable policy. In that spirit, Brazil last week announced a $60 billion program to shore up its currency. India has been introducing capital controls. South Africa is considering currency intervention. Blamed is the Federal Reserve’s taper talk. But as critical as we have been of Fed policy in recent years, emerging markets should stop crying and consider embracing long overdue reforms. We discuss who may win this battle as currency wars continue to rage.

[Hear More: Axel Merk: Treasuries No Longer the Place to Hide]

Plunging local currency, bond and equity markets have caught the attention of investors and policy makers alike. Weren’t emerging markets the new safe haven, with the old world synonymous with crisis? A lot of money had piled into comparatively small emerging markets. Investing in bonds of emerging markets had become particularly fashionable – and what was there not to like about them? Relatively attractive yields; tight management of exchange rates provided for the perception of low currency risk; and highly accommodative monetary policies the world over masked interest rate risk. But if something seems too good to be true, it likely is. Investors, including many that steadfastly proclaimed they have a “strategic allocation” to emerging markets, have since been scrambling to take their money out, as a double whammy in both falling prices and rising volatility overwhelmed them. We had been cautioning about hidden interest rate risks for some time, urging investors to consider reducing interest rate risk by moving towards the short end of the yield curve in local currencies that might offer much better value than “fashionable” spots in the emerging markets. Yield hungry investors wanted to hear little of that.

Similarly, many policy makers in local markets have not chosen the most constructive response:

- Complain. That’s really what policy makers the world over are best at: point the finger at someone else. Sure, policy makers rightfully complained about the Fed’s largesse causing distortions in their local markets. But complaining rarely fixes problems, especially when perceived interests across borders are not aligned.

- Take the money. Many emerging markets started issuing more debt in response to investor demand, which is politically convenient because popular domestic projects can be financed. Fostering increased liquidity in local debt markets on its own is laudable, but achieving increased liquidity merely by issuing more debt may be an ill-guided strategy making a country vulnerable when the music stops.

- Absorb the money. A number of emerging market central banks absorb inflows directly by issuing their own short-term debt. The advantage is that the capital won’t be directly available to governments or industry to spend, creating an unsustainable short-term boom (bubble). Such policies are typically aimed at preventing a currency from appreciating too much. On the downside, lured by the potential for currency appreciation, money usually does find a way into the country anyway, often into real estate. As such, while active reserve management helps to mitigate some of the pressure of hot money flows into a country, it’s not a panacea.

As the tide is turning, there’s talk of currency intervention and capital controls. We wonder how many days Brazil’s billion to support the markets will last. That’s because the root cause of the flight is a re-pricing of risk: emerging markets are risky – what a surprise! And when the U.S. sneezes, the rest of the world continues to be at risk of catching a cold. Well, the U.S. bond market may well enter a prolonged flu season and the rest of the world better be ready for it. In other words: we expect volatility in U.S. bond markets to persist, with particularly grave implications for emerging market local debt.

Rather than focus on the symptoms, policy makers in emerging markets should focus on fundamentals. Despite all the fiscal challenges in the U.S., why is it that foreigners have historically loved the U.S. bond markets? Part of it may be a mispricing of risk that will be a crisis for another day. But much of it is that U.S. markets are liquid. Most notably, a key reason why foreign central banks buy U.S. Treasuries in the billions is because of perceived liquidity. Liquidity isn’t merely a result of size, but of breadth, maturity and a predictable regulatory environment. Many readers may interject that not all is well with the predictability of the U.S. regulatory environment, nor the mindboggling size of the bond market; and we would be the first to agree that the trend has not been a good one. However, compared to many emerging markets, the U.S. still looks like a stable, advanced economy. Importantly, domestic criticism should not detract from the medicine that would be helpful for emerging and developed markets alike:

- Investor trust is built over the long-term. Take Brazil: you don’t banish speculators during the good times, then beg them to come back during bad times.

- Open markets are not merely about allowing a currency to float; it’s about providing investors with an opportunity to invest in more than just specific issues of government bonds. Countries fostering their domestic fixed income markets are less dependent on the U.S. dollar and U.S. investors. Developing domestic and offshore fixed-income markets is a key element. But also allowing other forms of investments, be that the development of capital markets or even just the rule of law for private limited liability companies.

- It’s also about developing a predictable regulatory environment. Countries interested in attracting long-term capital should give investors a sense of certainty as to how their capital will be dealt with in ten years.

During the good years, Indian policy makers were adamant that they wanted to limit money coming in, so that they would not have the same vulnerability as others. As the recent past has shown, replacing controls with even tighter controls does not instill investor confidence. China, on the other hand, has been moving towards opening its markets, if ever so slowly. China has long understood that developing the market as a whole is a precondition to allowing greater exchange rate flexibility. Aside from gradually developing fixed income markets, the regulatory environment has been maturing, even important reforms in the banking system to introduce more competition are under way. While China is a long way from where we would like them to be, we believe the government there is taking steps in the right direction, whereas policy makers in much of the rest of the world are on an ill-guided course.

[Listen: Russell Napier: Emerging Markets Faltering, Foretelling Deflation Ahead]

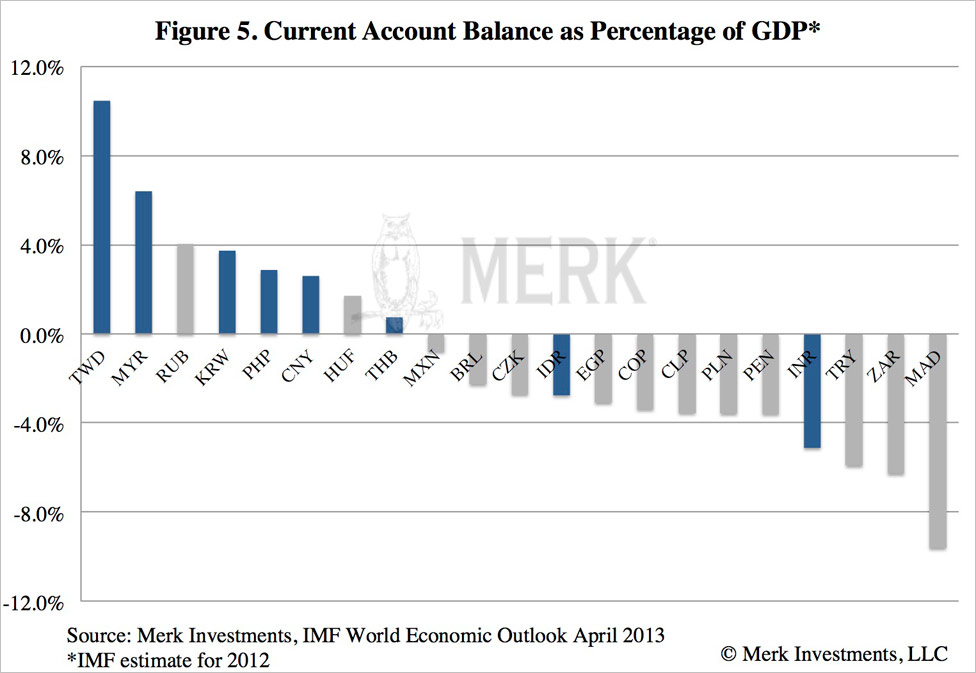

It is no surprise to us that Asian countries with strong external balances, such as China, Taiwan and Korea, have weathered the storm so far much better than India, Indonesia, South Africa or Brazil, and investors may want to deploy their capital selectively within the emerging markets Long-term investors may find better risk-adjusted returns in those countries embracing reform rather those fighting investors.

Source: Merk Funds