A key factor affecting the future of the country—with major implications for both investors and public policy—is the growth potential of the US economy. Among economists, equilibrium potential GDP is vigorously debated. Are we in a “new normal” slow-growth environment. Is the current slow growth we are experiencing as we emerge from the Great Recession “as good as it gets?” What determines the US growth potential, and how can we best think about it?

Economists have focused on both the determinants of aggregate demand and the productive capabilities of the economy as determinants of the growth potential of our economy. Here I will focus on the supply side of the equation since many prominent economists are now arguing that there are limits to US firms’ ability to innovate and experience productivity grow. One preeminent scholar—Robert Gordon of Northwestern University—argues that we are not going to be able to sustain the kind of growth we have experienced previously.[1] The reason is that, unlike the past, he sees our economy facing four headwinds that it didn’t face in the past: demographics in the form of an aging population, a steady accumulation of debt (both personal and public), an education deficit, and income inequality. The only force that could overcome these headwinds would be an acceleration in productivity growth from its current average of about 1% per year. However, Gordon argues that this is unrealistic since all the truly useful inventions that have transformed our economy and significantly improved the quality of human existence have already been discovered and incorporated into our daily lives. In his view we are looking at the world in which steady-state GDP growth will languish at only about 0.8% per year for the next 25 years—and that is not an optimistic prospect, especially for our children and grandchildren.[2]

Read ECRI's Lakshman: Fed on a Collision Course

Countering Gordon’s negative assessment, an equally eminent economist and economic historian, Joel Mokyr - also a professor at Northwestern University and a colleague of Professor Gordon—offers a very uplifting and far more optimistic view. In his opinion, the best is yet to come. He recently summarized his views in his presidential address before the International Atlantic Economic Society meetings in Washington, DC, on October 15, 2016.[3] Mokyr looks at the history and the conditions that spawned the advances in knowledge and productivity that we call the Industrial Revolution and evaluates how relevant they are today. Mokyr then extrapolates into the future, and concludes that “… if the patterns of the past hold (a big if), there is some reason to expect the rate of technological change to accelerate over the next decades….”[4]

Professor Mokyr identifies four conditions that create the climate for this acceleration in innovation and technological change. The first is “diversity and competition.” The Industrial Revolution and what followed was stimulated by competition among nations such that “… the political fragmentation and religious and cultural pluralism of Europe were keys to its success in the 18th and 19th centuries.” While we don’t have the collection of nation states that existed in the 18th century, competition due to globalization is clearly relevant and no less intense today with the growth of Europe, the dominance of the United States, and the emergence of countries in Asia and Latin America. One consequence of this globalization is that it has become difficult if not impossible for one nation or group of nations to thwart an innovation that might mean they would fall behind, just as was the case in the 18th and 19th centuries. Clear examples are the growth of the internet, China’s turnabout this year in embracing genetically modified crops, and the extension of cloning and stem cell research outside the US. Two important differences between today and the 18th and 19th centuries, however, are the increase in literacy and educational attainment that has drastically increased the pool of sophisticated scientists relative to the size of the population and the speed with which research, knowledge, and innovations are now spread. The lag between invention, innovation, and adoption is substantially less today and more talented people are involved in the process than ever before.

The second factor important to innovation and its spread is “incentives.” Here Professor Mokyr cites both negative and positive incentives. Positive incentives span everything from recognition, such as the Nobel Prize, to providing mechanisms, such as a well-functioning patent system, for innovators to protect and reap the rewards from their ideas. Indeed, many universities have well-established policies that encourage and support academic entrepreneurs in their efforts to convert research and innovations into profitable business enterprises. At the same time, industrial espionage and lack of respect for patents in some countries create barriers to growth and the extension of new ideas. A consequence is that, as the world has become more global, intellectual property and patent rights in cross-border situations have become an important political issue. On the negative side, intolerance and fear of new ideas have become less and less important as systems that support the contestability of ideas become more prevalent. Their existence, however, in some cultures and segments of the population has clearly stifled growth and progress in certain parts of the world, and even in some cases, in the United States.

Another important incentive and catalyst for innovation are the existence of real life problems that need solving. The list of such problems is diverse, and they are no less critical today than the problems of the past were in their time. And solving them promise great financial rewards. Current challenges include everything from the need to discover new sources of energy that don’t contribute to global warming to treating antibiotic-resistant infections. Can we cure cancer or solve the problem of Alzheimer’s disease and perhaps slow the human aging process? The list is long, and researchers in both academia and business are working to address those and numerous other major problems.

Read also Economic Breadth Is Significantly Deteriorating in the US

Professor Mokyr identifies a third crucial basis for optimism and innovation, which is the fact that science has routinely been able to create new tools that enable new avenues of research and innovation to proceed. Science has repeatedly pulled itself up by its own bootstraps Examples abound and includes the telescope, microscope, and barometer. All three were critical to the scientific revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries. In our era, the discovery of double-helix DNA has revolutionized medicine and immunology. We now beginning to see the development of gene therapies. The invention of a new gene tool, Crispr, which enables the cutting and pasting of gene sequences is now being used to modify crops and to engineer animals to even grow replacement human parts. The invention of 3D printing may revolutionize the manufacturing process by permitting mass customization of products and replacement parts to reduce inventory costs, not to mention the easy construction of prototype products. And the race is on to “print” human tissues and even transplantable organs. When lasers were developed in the 1960s, no one really knew what use might be made of them, but today they are employed in everyday commerce in the form of barcode readers, as measuring devices, and in medicine to correct everything from vision defects to gum disorders that in the past might have necessitated crude surgery, just to cite three among a myriad of other applications. Finally, today’s Wall Street Journal has an insert document called The Future of Everything that describes not only DNA computing and data storage but also provides an interesting glimpse at other technological advances including robots that are on the horizon.

The fourth factor that Professor Mokyr cites is the “computer,” which is itself a collection of innovative components, the most important being the transistor that replaced the vacuum tube. As transistors were miniaturized, they put the power of a 1970s supercomputer in the hands of virtually every citizen. But Mokyr’s emphasis is really more focused on the impact that the computer has and will likely have on science itself rather than its direct applications to improve productivity and workplace efficiency. The amplification of computing power now permits scientists to simulate a behavior and solve complex equations that could not be solved in the past. Computers also permit scientists to shortcut the testing and deployment of new drugs and other products that are a source of productivity growth. They control fighter airplanes that a human could not control or fly.

The bottom line of Professor Mokyr’s analysis is that there is every reason to believe that we are far from reaching the limits of invention and innovation. We don’t yet know whether new discoveries will prove as important to improving the human condition as the harnessing of electricity, the spread of indoor plumbing, or the widespread deployment of air conditioning turned out to be. But there is every reason to think that conditions are ripe for further transformative breakthroughs.

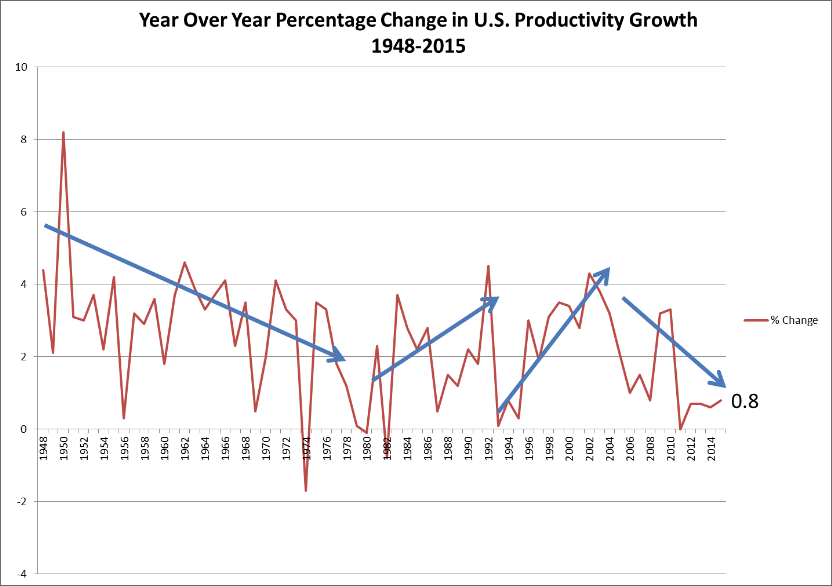

What the potential for transformative innovation means for investors is that we may not be reaching the limits of productivity advances, as Professor Gordon fears. This means that companies will continue to innovate, grow and expand. Indeed, we have gone through cycles of productivity advances and slowdowns since World War II, as the chart below demonstrates. Each down cycle was greeted with the claim that all the really important discoveries had already been made—a claim that has invariably been proven wrong.

Professor Gordon’s four headwinds do represent serious problems, but more for politicians and society at large than for scientists. We need to address the education deficit, not only to solve the skill mismatch problems that advances in technology bring but also to raise the overall standard of living and to mitigate the income inequality problem by enabling the bottom segments of society to improve their lot. The debt problem, especially at the national level, is rooted in a lack of fiscal discipline and the runaway growth of entitlements that have been promised but not funded. Finally, one way to address the aging problem is to fashion a forward-looking immigration policy.

A back-of-the-envelope approximation from economic growth theory implies that sustainable long run growth can be obtained approximated by summing the rate of growth of productivity and the rate of growth of population (and hence, the workforce). Today, as the chart above shows, productivity is growing in the range of 0.8% to 1.5%, and the US population is growing at less than 1%. This implies a sustainable rate of real GDP growth of from 1.8% to 2.4%. This is what we have experienced the last few years. But if Professor Mokyr is correct, we are not condemned to a world of 0.8% productivity growth, and it is within our power to ensure that a minimal growth world is not our future.

[1] For a quick summary of Gordon’s views, see his TED talk in NPR: “The death of innovation, the end of growth,” February 2013 at https://www.ted.com/talks/robert_gordon_the_death_of_innovation_the_end_of_growth

[2] https://news.northwestern.edu/stories/2016/04/gordon-v-mokyr-american-economic-growth

[3] See “Is Technological Progress a Thing of the Past?,” presented at the International Atlantic Economic Society annual meeting, Washington, DC, October 15, 2016.

[4] His views are developed in two books. A Culture of Growth: The Origins of the Modern Economy (Princeton, NJ; Princeton University Press, 2016) and The Lever of Riches: Technological Creativity and Economic Progress (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992).