Third Quarter Review

Before the financial crisis erupted in the fall of 2008 the big four central banks of the world (US Fed, European Central Bank, Bank of Japan, and the Bank of England) had combined monetary reserves of roughly $3 trillion dollars. Fast forward to the present and their combined reserves have almost quadrupled to a whopping…wait for it…$11 trillion dollars!

What has been the outcome of this unprecedented debt binge and monetary stimulus by the world’s central bankers? Michael Hartnett, Bank of America Merrill Lynch’s Chief Investment Strategist, helped to shed light on this question in his recent piece, “A Portrait of Quantitative Failure,” with some astounding figures, particularly as it relates to our savings accounts:

- $12.9T – Outstanding amount of bonds currently yielding less than 0% (29% of total).

- $24.6T – Outstanding amount of global central bank holdings of financial assets.

- -1.1% – The most negative bond yield in the world (3-Yr Swiss government bond).

- 107 Years – The time it takes to double your savings in 1-year US deposit account.

- 1387 years – The time it takes to double your savings in 1-year German deposit account.

- 6932 years – The time it takes to double your savings in 1-year Japanese deposit account.

- 1978 – The year US labor market participation rate was as low as it is today.

- 21,084,000 – The number of unemployed men and women in Europe.

- 49%, 45%, 39% – Youth unemployment rates in Greece, Spain, and Italy.

- 0.16% – The infinitesimal increase in Japan’s real GDP in the past 8 years.

If the above doesn’t paint the picture of an upside down world, I don’t know what does!

The natural question that comes to mind is how did we get here? There are two principal factors that first come to mind, known as the “twin D’s”: demographics and debt. Demographics play a huge role in economic growth rates as a rising working age population tends to lead to rising economic growth rates and vice versa. To understand how demographic trends impact the economy, we can use the baby boomers as a case study. As boomers entered the workforce in the late 1970s to early 1980s and started making a living, they drove US consumption trends by taking on debt and buying cars, homes, appliances, and other goods.

This drove economic growth rates and stock market returns higher in the 1980s and 1990s until the stock market reached bubble valuations at the 2000 peak. We had an echo bubble later in housing as former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan drove rates lower but after the housing bubble peaked so too did overall household debt relative to incomes. Boomers have come to realize they can’t rely solely on their stock market accounts or appreciation of their home for retirement and have responded rationally to their situation by cutting back spending and working longer if they can.

The Baby Boom movie we have been watching for the past several decades is now playing in reverse. Rather than earning income and spending it in the economy and adding to their 401ks, Boomers are now pulling down income from their accounts and in this low-interest rate environment even possibly eating into principal. This is one contributing factor for why we have been witnessing anemic economic growth rates during this cycle and have had subpar market returns for the past decade.

Demographics - “Peak Youth Is Coming”

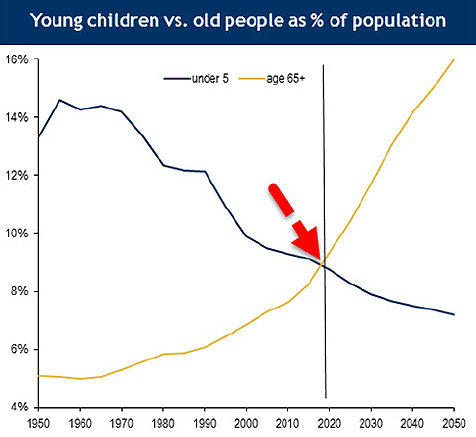

Economic growth will continue to be anemic with increased growth in the 65+ age cohort while the working age population as a percent of the total population declines. This is not just a US issue, however, but a problem confronting most of the developed world. We are nearing “peak youth” for the first time in human history as those under the age of 5 will be outnumbered by those aged 65 and over (see chart below).

With a greater share of the population moving into their wealth distribution phase (and a smaller portion in the wealth accumulation phase) future economic growth rates will be much slower than they have been in the prior decades. This is particularly true when considering that today’s generation of entrants to the workforce are saddled with significantly more debt (student loans) than when their parent’s generation entered the workforce.

Source: UN

The Debt Time-Bomb

The 2008 financial crisis was a major turning point for the US economy and financial markets. Prior to 2008, we had decades of debt accumulation in which banks lent and consumers, businesses, and governments borrowed with these loans fueling economic growth rates. To reinvigorate the debt cycle after recessions our central bank would lower interest rates to entice borrowers back to the debt altar to fuel the next bubble. Today we are staring at zero interest rates and, in many parts of the world, negative interest rates; yet we have been unable to see a strong revival in credit growth outside of a few select areas. As they say, “you can lead a horse to water but you can’t make it drink.”

High debt levels, a weak employment recovery, flat to declining wages, and greater economic and political uncertainty are all contributing factors that have led to a diminished appetite for debt by borrowers. Furthermore, increased financial regulation has made lenders less willing and able to extend loans. These factors have contributed to why generational low levels of interest rates have failed to meaningfully stimulate the economy here in the US and the rest of the world. Consumers are finally being forced to align their wants and needs.

What this means is that the twin tailwinds of a rising working age population and growing household debt growth over the prior three decades have come to an end and are likely to prove to be headwinds over the coming decade, thwarting the efforts of monetary and fiscal policy both here in the US and abroad.

From Quantitative Easing to “Helicopter Money”

The secular forces of growing working age populations, declining interest rates, rising trade globalization and debt accumulation accompanying the past few decades are not likely to be repeated ahead. As such, authorities are likely to attempt new policies in acts of desperation.

Central banks all across the globe have undergone several rounds of quantitative easing (QE) but as Bank of America’s Michael Hartnett has shown, QE should be replaced with “QF” or quantitative failure. Despite an upside down world created by global QE, the fruits of central bank labor have been for not. This is why unconventional monetary policy may become even more unconventional by teaming up with fiscal policy in the months and years ahead.

The idea of helicopter money came from the famous American economist Milton Friedman in his 1969 paper, “The Optimum Quantity of Money” in which he talked about the concept of central bank money printing bypassing the commercial banking system and going straight to households. Former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke commented on this concept back in a 2002 speech, which earned him the nickname “Helicopter Ben.” Here’s what he said:

A broad-based tax cut, for example, accommodated by a program of open-market purchases to alleviate any tendency for interest rates to increase, would almost certainly be an effective stimulant to consumption and hence to prices. Even if households decided not to increase consumption but instead rebalanced their portfolios by using their extra cash to acquire real and financial assets, the resulting increase in asset values would lower the cost of capital and improve the balance sheet positions of potential borrowers. A money-financed tax cut is essentially equivalent to Milton Friedman’s famous ‘helicopter drop’ of money.” (source)

The following article illustrates the difference between QE and helicopter money:

The major difference between QE as it has been carried out and helicopter drops as envisaged by Friedman is that the vast majority of purchases have been asset swaps, where a government bond is exchanged for bank reserves. While this alleviates reserve constraints in the banking sector (one possible reason for them to cut back lending) and has lowered government borrowing costs, its transmission to the real economy has been indirect and underwhelming.

As such, it does not provide much bang for your buck. Direct transfers into people’s accounts, or monetary-financed tax breaks or government spending, would offer one way to increase the effectiveness of the policy by directly influencing aggregate demand rather than hoping for a trickle-down effect from financial markets. (source)

Where are the helicopters likely to fire up first?

Japan – A Case Study of the Future

Japan was the first developed country to see its debt cycle peak back in the early 1990s as private debt as a percent of GDP peaked near 220%, and has since declined to roughly 170%. On the other hand, Japanese government debt to GDP has risen to 229%. That might not mean much to you but consider this: in response to their own debt crisis, the Bank of Japan lowered its discount rate to 0.5% in the middle 1990s and it has averaged 0.3% for the past quarter century!

Despite rising government debt levels and record low-interest rates, the country continues to display stagnant growth as Japan witnesses a rising retirement population that is focused on savings and running down their wealth rather than earning income and building their retirement portfolios. For this reason, Japan may become the first country to adopt so-called “helicopter money” as the following article highlights:

Talk of further unconventional monetary policies globally has increased as Japan reaches the limit of what negative interest rates and quantitative easing can achieve.

That has sparked speculation that the Bank of Japan may adopt a policy of so-called helicopter money.

Dr. Loretta Mester, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland and a member of the rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), signaled direct payments to households and businesses to stoke spending was an option central banks might look at in addition to interest rate cuts and quantitative easing.

"We're always assessing tools that we could use," Dr. Mester said in response to a question from the ABC about the potential use of helicopter money.

Dr. Mester's cautious response to the helicopter money option follows recent comments from the Federal Reserve chair Janet Yellen that the measure could be used in "extreme situations". (source)

Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is wildly speculated to be preparing a fiscal stimulus package of roughly 20 trillion yen (7 billion USD) to jump-start Japan’s economy, which is showing further signs of slowing economic growth and deflation. In what is being termed a “soft” form of helicopter money the Bank of Japan is likely to expand its monetary purchases in conjunction with the expanded fiscal policy as the next step closer to outright helicopter money.

Soft helicopter money in Japan, relaxed austerity in Europe, expanded monetary stimulus by the Bank of England in reaction to the Brexit vote, and a US Fed on hold has propelled US markets to record highs. With the S&P 500 moving well past 2,100 and the Dow Jones Industrial Average past 18,000, market valuations are becoming closer to “bubble-like” valuations. Consider the following chart from Doug Short at Advisorspectives.com, which shows the market’s valuation is currently 76% above its historical average, making it the third highest behind the tech bubble and the boom of the late 1920s leading up to the Great Depression.

Source: Doug Short

When the market becomes overvalued and begins to correct, rarely does it stop at its mean but rather continues well below it. The March 2009 bear market bottom is a good example as stocks fell 12% below their historical average before starting a new bull market. Meaning, while we are 76% above the historical average, we could fall even further.

The market is becoming more and more expensive—that much is true. However, we are also seeing the economy continue to slow and recessionary risks rise, which is why many well-known strategists are approaching the spike to new all-time highs with caution. Consider Rosenberg: I'm Approaching This Rally With a 'High Dose of Skepticism':

When I look at valuations…I'm not going to say that the markets are in bubble territory but it's just a little too expensive for me right now. When you really back it out, if you're buying this market at this point you ipso facto have a view that earnings are going to rebound 25% from here in the next year. Well, we've seen earnings go up 25% in a year one-tenth of the time historically so that to me is not really a fair bet so...I'm looking at this rally I would have to say with a high dose of skepticism.

Though central banks may resort to new measures of monetary stimulus and even throw “helicopter money” from the skies, economic and market cycles are immutable forces of nature, often made worse by attempts to control or manage their behavior. Whether that means an epic market bubble, years of stagnation, or otherwise, remaining flexible and proactive is a must to thrive in today's upside down world.