As will be demonstrated herein, using both historical and present-day events, key aspects of current deflationary theory can be characterized as the combination of 1) an absurdity; 2) a misunderstanding; and 3) an oversimplification; all working together to create 4) a serious danger for investors.

Few questions are of greater concern for investors than: "will it be inflation or deflation that will dominate the coming years?"

This has been a topic of ongoing and sometimes heated debate. However, could it be that the correct reply to this pivotal issue is... "wrong question"?

The very common belief that it must be one or the other — either inflation or deflation — is one of the myths that we will explore. Indeed, the premise behind the question itself is dangerously mistaken, and investors believing those to be the only two choices face multiple kinds of unnecessary risks for years and even decades to come.

First, let me clarify that if one goes by the common and very simplified use of the term "deflation", then I am not a "Deflationist". For I believe that the value of all of our money is very much at risk in the years ahead.

However, I am indeed an asset deflationist, and have been so for a long time. That is, I strongly believe that decreases in the value of investment assets in purchasing power terms is one of the largest dangers facing investors in the years ahead.

Now the distinction between the simple term "deflation" and the much more precise term "asset deflation" is no mere technical one. And indeed, understanding the difference has the potential to transform the way one interprets the financial world of both the past and present, and could lead to potentially quite different strategies for future investment.

In this two-part series, we will:

1) Uncover the elementary "apples and oranges" mistake at the heart of many Deflationist theories, which is the failure to distinguish between currencies backed by tangible assets — and currencies which are not (such as today's US dollar);

2) Show that the central monetary lesson of the US Great Depression of the 1930s is not, as commonly believed, the unstoppable power of deflation. Instead, history proves the direct opposite, which is that a sufficiently determined government can smash monetary deflation and replace it with inflation — at will and almost instantly, even in the midst of a depression;

3) Refute the very common but dangerously mistaken belief held by many investors, which is that asset deflation — the falling value of assets in purchasing power terms — somehow protects the purchasing power of their (symbolic) money, so they no longer have to worry about inflation; and

4) Reject the commonly-held perspective that inflation versus deflation is some sort of neutral, market-driven battle between economic forces, and recognize that rather than a neutral playing field, there is an arena designed and managed by the government in which the predominant force is deliberate governmental interventions. For the government has overwhelming incentives to create a particular range of outcomes for its own benefit, each of which will systematically strip wealth from investors in a manner which few investors will fully understand — meaning few will be able to defend themselves.

The Great Depression: A Succinct Statistical Summary

The Dow Jones Industrial Average reached a peak of 381 on September 3, 1929. By July 8, 1932, it had hit its floor of 41, a plunge of 89% in less than 3 years.

The United States Gross Domestic Product was $103 billion in 1929. By 1933 it had fallen to $56 billion, a decline of 46%.

Accompanying the free fall in both the economy and the markets, price levels were falling as well — meaning that the value of a dollar was rising rapidly. The Consumer Price Index was at a level of 17.3 in September of 1929, and by March of 1933 had fallen to a level of 12.6. So what had cost a dollar in 1929, only cost 73 cents (on average) by 1933. This 27% deflation — or decline in the average cost of goods and services — represented a 37% increase in the purchasing power of a dollar.

For some, the effect of this deflation was to increase both their wealth and their standard of living. These are the people who had substantial money in savings — whether it was physical cash, or fixed-denomination financial assets that had survived the economic turmoil (such as accounts in banks that did not go bust), or the bonds of companies that did not default. For these individuals, all else being equal, their standards of living rose because they had the same number of dollars, and each dollar bought more than it had previously.

However, for most of the nation (and the world), this increase in the value of a dollar was achieved at great cost. The reason behind the increase was that dollars had become scarcer for businesses and most individuals. The destruction of the banks and much of the financial markets had dried up access to money on attractive terms. Widespread unemployment meant fewer dollars available to buy goods and services, which drove down the prices, which is what dropped the Consumer Price Index.

Most importantly, the deflation was not independent of the plunge in the markets and economy, nor just a result of it. Instead, as most economists agree, this monetary deflation was actually a reason why the Great Depression got as bad as it did.

Because there was not enough investor money, the source of funding for growing businesses was gone. Because they didn't have enough money, consumers were not spending. And because there wasn’t enough spending, businesses had to lay people off. Which further reduced consumer spending.

The nation was caught in a vicious deflationary cycle, which it seemingly could not break out of.

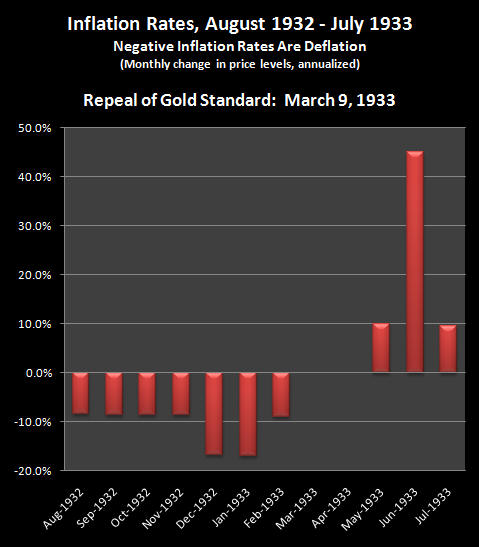

Yet, the United States did break out of the deflationary cycle, as illustrated in the graph above. After rapidly plunging for about 30 months, with the CPI seemingly in free fall and not able to find a floor — there was an abrupt turnaround. Not only was a floor found, but an immediate cycle of inflation replaced the seemingly unstoppable deflation. The nation essentially “turned on a dime”, from deflation to inflation instead. It is a cycle of inflation that has continued until this day.

What happened?

March 9, 1933

President Franklin D. Roosevelt was inaugurated on March 4, 1933. He came into office with a mandate and agenda to stop the Depression, and that meant breaking the back of the deflationary spiral. His actions were swift, beginning with a mandatory four-day bank holiday imposed the day after his inauguration.

Five days after Roosevelt took office, on March 9th, the Emergency Banking Relief Act was passed by Congress. This was the first in a series of executive orders and bills that would take place over the following weeks and year, and would cumulatively take the United States government off the gold standard — and would also effectively confiscate all investment gold from US citizens at a 41% mandatory discount.

Prior to this time — from 1900 to 1933 — the US government had been on a gold standard, and had issued gold certificates. In a matter of days in March of 1933, there would be a radical change — a veritable 180 degree turn — that would not only repeal the gold standard, but effectively make the use of gold as money illegal in the United States.

Fallacy One: Confusing Apples & Oranges

There is a common simplification that people make when they look at money over time. They think that a dollar is a dollar, even if the purchasing power has changed a bit. This is a quite understandable mistake, particularly if your profession does not involve the study of money.

When we look back over history, however, nothing could be further from the truth. This assumption instead reflects an elementary logical error which could be quite dangerous for your personal future standard of living if it leads to your drawing the wrong conclusions.

The term “dollar” is only a name (the same holds true for the “pound”, “franc”, “peso”, “mark”, and all other currencies).

What matters is not the name, but the set of rules — or collateral — that back the value of the currency during a given historical period. When we look back over long-term history, then sometimes it is gold, sometimes it's silver, sometimes it's both — and sometimes it is something else altogether. (As a creature of politics, money has always been of a complex and quite variable nature, given enough time.)

So when we say history “proves” something about a currency, we need to be very, very careful that we are comparing apples to apples, rather than apples to oranges. For instance, when we look at precious metals-backed currencies, the deflation of 1929 to 1933 when the US was on the gold standard was nothing new. It was just the latest development in the ongoing cycle of inflation and deflation that characterizes this type of currency.

Indeed, there were four major deflationary cycles during the century before Roosevelt ended the domestic gold standard. And the deflations of 1839-1843 and 1869-1896 were each much larger than the deflation of 1929-1933, with the dollar deflating roughly 40% in each of those earlier deflations.

This deflationary history does not, however, reflect the value of the “dollar” (as we currently know it) bouncing up and down, but rather the value of the tangible assets securing the dollar bouncing up and down around a long term average.

Going off the gold standard wasn't anything new either. Many nations have gone through periods, particularly during wars, when more money was needed than there was gold or silver to back it up. So, they issued symbolic (fiat) currencies that were backed only by the authority of the government, or they debased the metals content of the coins.

These fiat currencies almost always turned out badly. Instead of cycling up and down in value over time, they tended to go straight down and never come back up. While global monetary history is complex and long, it is highly, highly unusual for a symbolic currency to experience major and sustained deflation at the levels that are the norm with precious metals-backed currencies.

It is this quite understandable but mistaken belief that "a dollar is a dollar” which creates the ironic situation of many millions of people believing that the deflation of the US Great Depression proves the case for deflationary dangers in the current low or no-growth, high unemployment and high debt economic situation. Not at all — what we have instead is the elemental logical fallacy of equating apples with oranges.

Yes, the US experienced powerful monetary and price deflation during the early years of the Great Depression, but that was with a dollar that was backed by gold. In other words, it was a currency that was almost the diametric opposite of today's dollar, which is nothing more than a symbol. With the steward and protector of that symbol's value, the Federal Reserve, being engaged in a multi-year program of quantitative easing that involves creating trillions of new symbols (dollars) out of thin air without restraint.

So, then, the only thing the dollar of 1900 to early 1933 has in common with the post-2008 dollar is the word "dollar". Yet, that has been enough to create this fundamental confusion.

Fallacy Two: Reversing the Historical Lesson

Let’s revisit the sequence of events. The United States was stuck in a powerful deflationary spiral with a gold-backed currency, that seemed unstoppable.

So, the government changed the rules, and replaced the old dollar with a new dollar, whose value was not based on gold. And what happened?

In the depths of depression, and at the height of a deflationary spiral, the government successfully broke the back of deflation within one week. In the midst of deflationary pressures far greater than what we are seeing today, the government not only stopped the deflation, but reversed it with inflation. Indeed, by May of 1933 — only two months after the currency rules were changed — the monthly rate of inflation hit an annualized rate of 10%, and even hit a 40%+ (annualized) monthly rate by June of 1933.

For someone who is concerned about a new US depression leading to unstoppable price or monetary deflation based on what they believe happened in the 1930s, let me suggest they study the above graph carefully, and with a particular focus on March of 1933. And to remember as well the one near-universal lesson from the long and convoluted history of money, a rule which has particularly powerful implications at this time and the years ahead: every time the rules governing a currency lead to a problem that causes too much pain for a government to bear — the government just changes the rules and changes the nature of money.

And the bigger the problem — the bigger the rules change, the more the nature of money itself changes, and the bigger the resulting redistribution of wealth.

So, when we look not at the gold certificates of long ago, but at the dollar we have today, what the Great Depression of the 20th century in the United States historically proves is not the unstoppable power of deflation, but rather the opposite: that a sufficiently determined government can smash deflation at will, virtually instantly, even in the midst of depression, and replace it with inflation.

In the process of breaking the back of deflation — the nature of the dollar itself fundamentally changed.

Throughout the 19th century and the first thirty years of the 20th century, the value of the dollar went both up and down, as the (usually) gold-backed currency experienced regular cycles of both inflation and deflation. This cycle was replaced entirely by a new pattern — which could be characterized as down, down, down, as illustrated in the graph below.

(The graph above may look like it starts at 95 cents, but it doesn’t, it starts at .00. The fall in the value of the dollar in 1933, once the gold standard was abandoned, was so fast it can’t be seen with a 80 year scale and monthly increments.)

An 80 year old man or woman born in the 19th or 18th centuries would have seen the value of their currency fluctuate both up and down over their lifetimes, and there was a pretty good chance that at age 80, the dollar (or pound) would be worth the same or more than it was when they were born. When the US Government fundamentally changed the nature of money in 1933, it created an entirely different pattern: all down, and no up, so that for an 80 year old person today, a dollar will only buy what 5 cents did at the time they born.

So as we try to determine whether the current danger ahead is inflation or deflation, what is the monetary lesson from the US Great Depression?

The common belief is that the Great Depression demonstrates the awesome power of deflation, which the government can have a great deal of difficulty in fighting, if it can fight it at all. This is an extraordinary misunderstanding, and constitutes the second of our logical and historical fallacies.

What the Great Depression in fact showed was that if you have a tangible asset-backed currency such as gold or silver, and you enter a depression, then as history has demonstrated time and again, you're likely to have a period of substantial deflation.

However, what the events in March of 1933 show us is that even in the midst of a terrific burst of asset deflation and a terrible depression, if you take away the tangible assets that back your currency and you introduce a purely symbolic currency, then the force of inflation that is associated with a purely symbolic currency (as well as the changes in monetary policy that are thereby enabled) can be so powerful that it smashes the deflationary monetary pressures.

Indeed, the historical lesson to take away is that the value of money can turn on a dime when we are using a symbolic currency. Here we have absolute proof that even in the middle of a depression, the government has the power to stop a deflationary spiral at will. We can further see that this deflation-crushing strategy was not a one-time anomaly, but was so successful that it broke the ongoing inflation/deflation historical cycle, and led to a 95% destruction of the value of the dollar over the next 80 years.

What's in a Name?

The 2nd half of this article explores how changes in the nature of the US dollar since the year 2000 - without the name itself changing - not only refute much of deflationary theory, but have been a dominant economic and investment force during that time. Indeed, these changes have profoundly impacted the lives of many millions of people around the world and — even while little understood - have transformed performance across all major investment categories.