The following is an excerpt of the Browning Newsletter, a key source of information in describing the relationship between macro weather-related trends and their potential impact upon energy, commodities, and the wider global economy. To subscribe to her monthly newsletter, click here.

China, like the US, has had its precipitation patterns severely altered by the changed Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO). However, as a nation dominated by seasonal monsoons, the impact has been much more complex. In North America, most of the West became drier when the positive PDO phase (which had unusually warm conditions in the Eastern and Tropical Pacific) faded and the waters off the West Coast cooled. In China, the strength of its monsoons was shaped by the contrast between the land and water masses. When the PDO became negative and the Western and Northern Pacific became warmer than average, it strengthened the Northwest Pacific Monsoon in the north and central regions and weakened South China Sea Monsoon (called plum rain season in China) in southern areas.

This change in the Northwest Pacific Monsoon means that the northern and central portions of the nation tend to have wetter, warmer, and better growing seasons. At the same time, the wet season of the monsoon lasts longer, so harvest seasons are wet. This creates severe problems both for harvesting and crop storage. At the same time, the winter monsoon has become stronger, so winters are frequently colder and drier – not good for winter wheat.

Meanwhile, the southern portions China have a weaker monsoon, which means the summertime plum rains don’t extend inland. This can create severe problems at the headwaters of the Yangtze and Pearl River systems. The warmer waters allow stronger monsoons to slam the nation and flood previously drought stricken regions.

[Hear More: Evelyn Browning Garriss: Something for Everyone - Heat, Cold, Floods and Drought!]

Both China and the US are at similar latitudes and much of the cropland has similar weather and growing conditions. Back in the 1960s, when the PDO was in the same negative phase as today, the US government made a map showing equivalent croplands for the two nations. Frequently, one can get a good estimation of how Chinese crops are going by looking at how their North American equivalents are faring. (Chinese data is hard to achieve while US weekly data is easily accessible.) Notice the huge area of Southern China below that is equivalent to Oklahoma, which went through two years of drought and has endured heatwaves and flooding rains this summer.

Like the US, China is large enough to stretch across multiple climate zones. This means that normally, when one agricultural region is suffering, the other is prospering. One of the keys to China’s long history is the lifesaving trade between climate zones. This year, both North and South China have had crop-damaging weather that will necessitate importing grain.

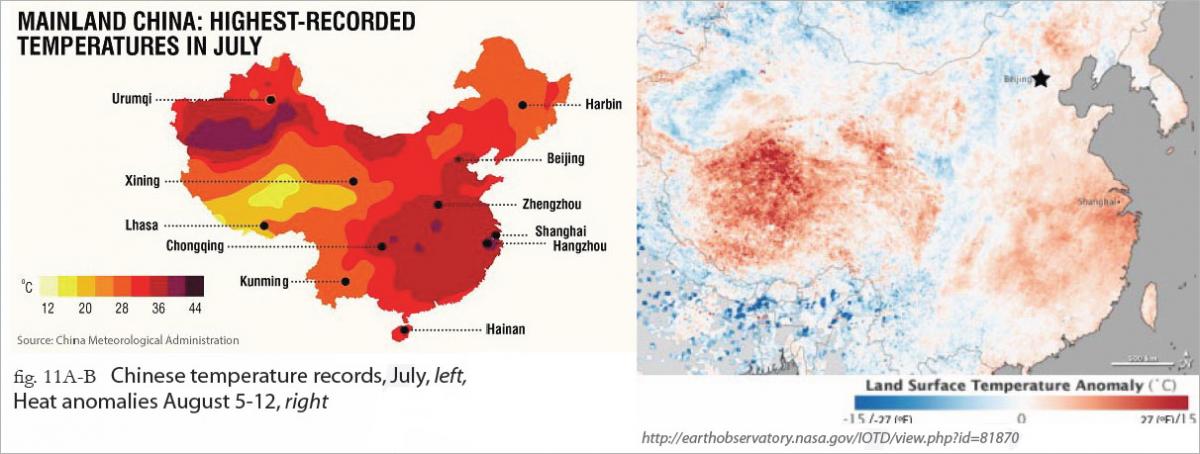

East China had a horrendous record-breaking heatwave, the worst in 140 years. It has lasted through July and most of August, breaking urban heat records and subjecting croplands to the greatest heat in over 50 years. At least 40 people died during the heat wave, including ten in Shanghai, according to the Xinhua news service.

The heat affected the most populated third of the nation, at least 19 provinces and 40 major cities. Chinese headlines announced fish die-offs and severe damage to crops. Chinese officials have worked to keep food prices stable, although there have been increases in vegetable prices.

This heat has only added to the problems created by extreme precipitation. Some areas of the nation are still plagued by continuing drought. The largest problem, however, is flooding. In the south, Typhoon Utor, Trami and other raging storms created deadly floods and landslides.

The more important picture is the persistent rainfall and flooding in China’s critical Northeastern croplands. The USDA’s August 30 Commodity Intelligence Report warns that this summer’s Northeastern China’s rainfall was 40 to 50% above normal, flooding and water-logging crops. In the excellent Global Commodity Intelligence Daily, they reported, “It is critically important that Heilongjiang – indeed, the whole of the Northeast – is suffering through a season of unprecedented floods, landslides, and bursting dams all amid erratic temperatures. The affected regions along with Inner Mongolia together produced 42.9% of China’s corn in 2012.” They also are major rice and soybean producers. August 18 – 24 shows a break in the regional rainfall, but there has been substantial damage.

China is already the world’s greatest importer of rice, quadrupling from the previous year. The Chinese Daily has announced that its wheat imports are tripling and it will probably be the world’s greatest wheat importer in 2014. The current weather conditions signal additional large increases in corn and soy imports. The world should expected higher prices in these commodities due to the Chinese weather problems in key growing areas.

Conclusions

US crops, as long predicted, are facing problems west of the Mississippi, with heat and dry conditions reducing yield. Meanwhile there is a risk of early freeze and a wet harvest in the Midwest. Other Northern Hemisphere nations are facing similar problems and many of them have a much poorer agricultural infrastructure for coping with these difficulties.

Given the problems in China, there should be increased, even heavy demand for grain and oilseed. With the mixed global outlook, much of the buying will be from the US.

Source: Browning Newsletter