Recently, the International Energy Agency’s Chief Economist Fatih Birol was quoted as saying,

In the next 10 years, more than 90% of the growth in global oil production needs to come from MENA [Middle East and North African] countries. There are major risks if this investment doesn’t come in a timely manner.

While I agree that we need more oil production, I think we are kidding ourselves if we expect that 90% of the needed growth in global oil production will come from MENA countries. In this post, I will explain seven reasons why I think we are kidding ourselves.

Reason 1. MENA’s oil production, as a percentage of world oil production, has not increased since the 1970s, suggesting that MENA really cannot easily ramp up production.

Figure 1. Middle East and North Africa oil production as percentage of world oil production. Figure also shows oil price in 2010 dollars. Amounts are from BP Statistical Report. Oil includes NGL; oil price comparable to Brent.

MENA’s oil production amounted to more that 40% of the world’s oil production back in the mid-1970s, but is now down to 36% of world oil supply. It is hard to see anything that looks like an upward trend in MENA’s share of world oil supply, even when high prices hit. OPEC talks big, but its actions do not correspond to what it says.

Reason 2. MENA claims huge oil reserves, but these reserves have not been audited, and there is little evidence that they can really be transformed into corresponding oil production in any reasonable time-frame.

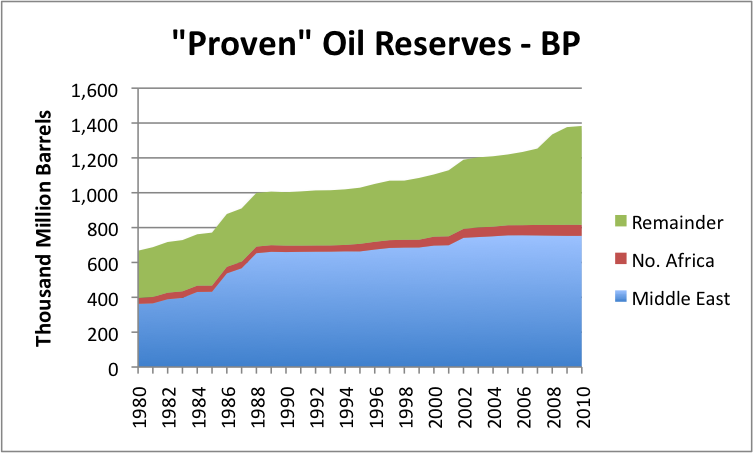

Figure 2. World's "proven" oil reserves, according to BP Statistical data, split between Middle East, North Africa, and the Remainder of the World

Countries don’t all use the same standards when reporting oil reserves. Reserves of countries following SEC reporting requirements have historically been conservative, but Middle Eastern countries do not follow these standards. A small country with high oil reserves will appear rich to the rest of the world, and its leader will appear important in the eyes of local residents, so there can be a temptation to “stretch” the amount reported. There is no timeframe specified with respect to the stated reserves, either. If the oil is very heavy or difficult to extract, the expected extraction period could be hundreds of years.

Because of these issues, it does not necessarily follow that high oil reserves mean that with only a little effort, production can easily be increased. The Wall Street Journal published an article called Facing Up to End of ‘Easy Oil’ which talks about the lengths to which Saudi Arabia (with Chevron’s help) is going to develop techniques to steam out the Wafra field’s thick oil. If there were easier-to-obtain high-quality oil, Saudi Arabia would no doubt be working on the other sources, instead.

Reason 3. Saudi Arabia has said it does not intend to increase its capacity for oil production. According to the Oil and Gas Journal:

Birol’s comments [quoted above] came just days after Saudi Arabian Oil Co. Chief Executive Officer Khalid Al Falih told the Wall Street Journal that his country had no plans to increase oil production capacity to 15 million b/d [barrels a day], given the expansion plans of other producers such as Brazil and Iraq.

“There is no reason for Saudi Aramco to pursue 15 million b/d [of output capacity],” said Al-Falih, whose remarks ended speculation that arose in 2008 when Saudi Arabia’s Oil Minister Ali I. Al-Naimi said his country could boost its capacity by another 2.5 million b/d to 15 million b/d.

The excuse that Saudi Arabia gives is really strange (from same article):

“It is difficult to see [an increase in capacity] because there are too many variables happening,” Al-Falih said. “You’ve got too many announcements about massive capacity expansions coming out of countries like Brazil, coming out of countries like Iraq. The market demand is addressed by others.”

This is a strange statement to make; it is like General Motors saying it is not going to add automobile production, because Ford will be selling as many cars as buyers will want. If it is really making a profit on each barrel, why would it do this, unless it really is not capable of making the expansion it claims?

Reason 4. While Saudi Arabia claims current production capacity of 12.5 million barrels a day, this amount is not audited, and its actual capacity is quite possibly lower. Its highest recent production is 9.84 million barrels a day.

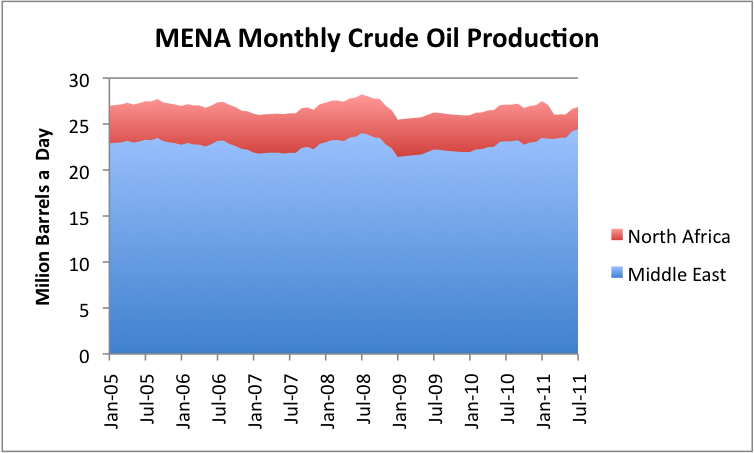

When Libya’s oil production was taken off line, Saudi Arabia was not able to make up for the loss with the type of oil that the market required. Recently, Saudi Arabia made a statement that it would ramp up production to 10 million barrels a day, its highest in 30 years. Saudi Arabia did manage to increase its crude oil production to 9.84 million barrels a day in July, 2011, an increase of 700,000 to 900,000 barrels a day over recent months’ production. But even with this big ramp up, MENA crude oil production has not made up for the shortfall in Libya production (Figure 3). And of course, Saudi production is still far short of the claimed 12.5 million barrel a day capacity.

Figure 3. MENA Monthly crude oil production, based on EIA data.

Reason 5. MENA’s oil consumption is rising, so even if MENA’s production should rise, the rest of the world would not necessarily get much benefit from it.

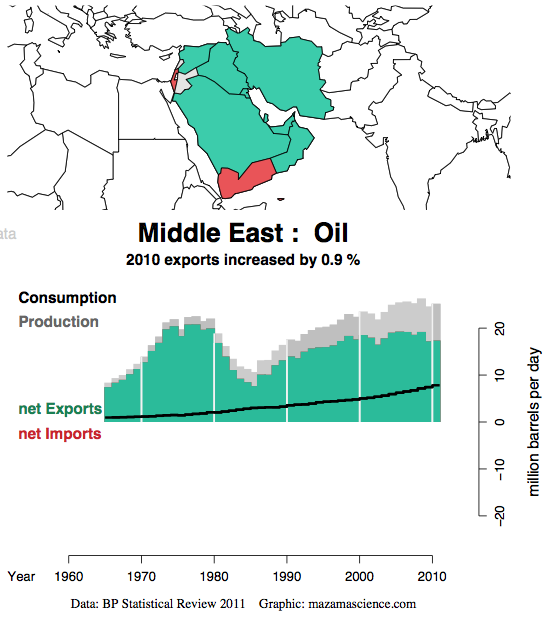

Figure 4. Middle East oil production, consumption, and net exports, based on BP Statistical Data, from Energy Export Data Browser. Oil includes natural gas liquids.

The amount shown in green in Figure 4 is the amount of oil exports. These are declining, because consumption is rising, while production is flat. The above graphic is for the Middle East only, but MENA in total is showing a similar pattern of rising consumption leading to less exports.

Reason 6. Instability is a huge problem in the Middle East, leading to rising and falling oil production. This is especially the case for Iraq, a country which has planned large production increases.

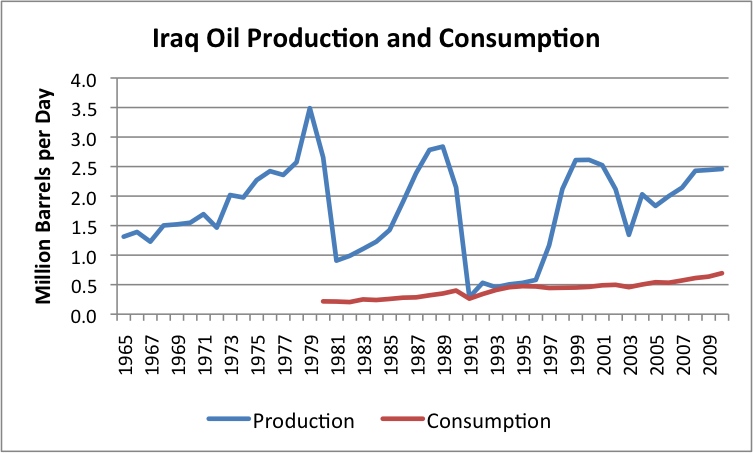

Figure 5. Iraq oil production and consumption. Production from BP Statistical Data; consumption from EIA data.

Figure 5 shows the extent to which oil production has varied in Iraq since 1965, as a result of past instability. Overcoming this pattern will be difficult. Besides instability, there is a need to add a huge amount of new infrastructure–particularly additional port capacity to handle increased oil exports. Both the problems with instability and the need for new infrastructure will make it difficult to ramp up Iraq’s oil production quickly.

Iraq plans to increase its oil production to 6.5 million barrels a day by 2014, and to reach 12 million barrels a day by 2017. Neither of these targets will be possible without huge investment and political and economic stability. These targets are seen as unreasonably high by many.

Reason 7. High oil prices lead to high food prices, and a recent study shows that high food prices are associated with riots. So the high oil prices required to produce the difficult-to-extract oil are likely to sow the seeds of governmental overthrow (repeat of “Arab Spring”) and political instability in MENA countries.

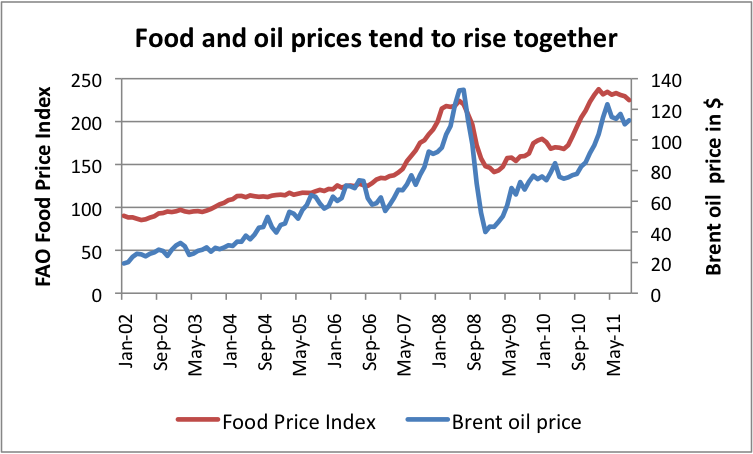

Figure 6. Comparison of FAO Food Price Index and Brent Oil Price Index, since 2002.

Figure 6 shows the correlation between food and oil prices. A person would expect food and oil prices to be highly correlated because oil is used in the production and transport of food products. The FAO Food Index relates to imported food, such as is often used in MENA countries. Because this food is often transported long distances, a person would expect its cost to be especially affected by oil prices.

A recent academic study called The Food Crises and Political Instability in North Africa and the Middle East by M. Lagi, K. Bertrand, and Y. Bar-Yam shows this graph:

Figure 7. Figure showing correlation between riots and high food prices, as measured by FAO Food Price Index from https://arxiv.org/pdf/1108.2455v1

The authors show that there is a high correlation between high food prices and riots. They say, “If food prices remain high, there is likely to be persistent and increasingly global social disruption.” They also point to the possibility of the situation getting much worse, in the 2012-2013 timeframe, as a result of a continuing rise in food prices.

We saw in Figure 6 that rising oil prices are associated with rising food prices. Thus, the fact that oil prices are rising because the “Easy Oil” has mostly already been extracted, and we now are moving on the more expensive oil, could contribute to riots. This association is likely to make it more difficult for MENA to raise oil production, because riots lead to political instability, and without political stability, it is difficult to increase or even maintain current levels of production.

* * *

For all of these reasons, depending on MENA for 90% of the growth in global oil production between now and 2020 seems unwise. I have shown in previous posts that what the world really needs is a rising supply of low-priced oil, if we are to avoid long-term recession. But MENA is unlikely to supply this. The Middle East claims huge oil reserves and Iraq offers high production targets, but in the end, we are likely to be kidding ourselves, if we believe that these will fix world oil problems.

Source: Our Finite World