In recent weeks, we have been focusing on Greece, Germany, Ukraine and Russia. All are still burning issues. But in every case, readers have called my attention to what they see as an underlying and even defining dimension of all these issues — if not right now, then soon. That dimension is declining population and the impact it will have on all of these countries. The argument was made that declining populations will generate crises in these and other countries, undermining their economies and national power. Sometimes we need to pause and move away from immediate crises to broader issues. Let me start with some thoughts from my book The Next 100 Years.

Reasons for the Population Decline

There is no question but that the populations of most European countries will decline in the next generation, and in the cases of Germany and Russia, the decline will be dramatic. In fact, the entire global population explosion is ending. In virtually all societies, from the poorest to the wealthiest, the birthrate among women has been declining. In order to maintain population stability, the birthrate must remain at 2.1 births per woman. Above that, and the population rises; below that, it falls. In the advanced industrial world, the birthrate is already substantially below 2.1. In middle-tier countries such as Mexico or Turkey, the birthrate is falling but will not reach 2.1 until between 2040 and 2050. In the poorest countries, such as Bangladesh or Bolivia, the birthrate is also falling, but it will take most of this century to reach 2.1.

The process is essentially irreversible. It is primarily a matter of urbanization. In agricultural and low-level industrial societies, children are a productive asset. Children can be put to work at the age of 6 doing agricultural work or simple workshop labor. Children become a source of income, and the more you have the better. Just as important, since there is no retirement plan other than family in such societies, a large family can more easily support parents in old age.

[See: Exploring the Clash Within Civilizations]

In a mature urban society, the economic value of children declines. In fact, children turn from instruments of production into objects of massive consumption. In urban industrial society, not only are the opportunities for employment at an early age diminished, but the educational requirements also expand dramatically. Children need to be supported much longer, sometimes into their mid-20s. Children cost a tremendous amount of money with limited return, if any, for parents. Thus, people have fewer children. Birth control merely provided the means for what was an economic necessity. For most people, a family of eight children would be a financial catastrophe. Therefore, women have two children or fewer, on average. As a result, the population contracts. Of course, there are other reasons for this decline, but urban industrialism is at the heart of it.

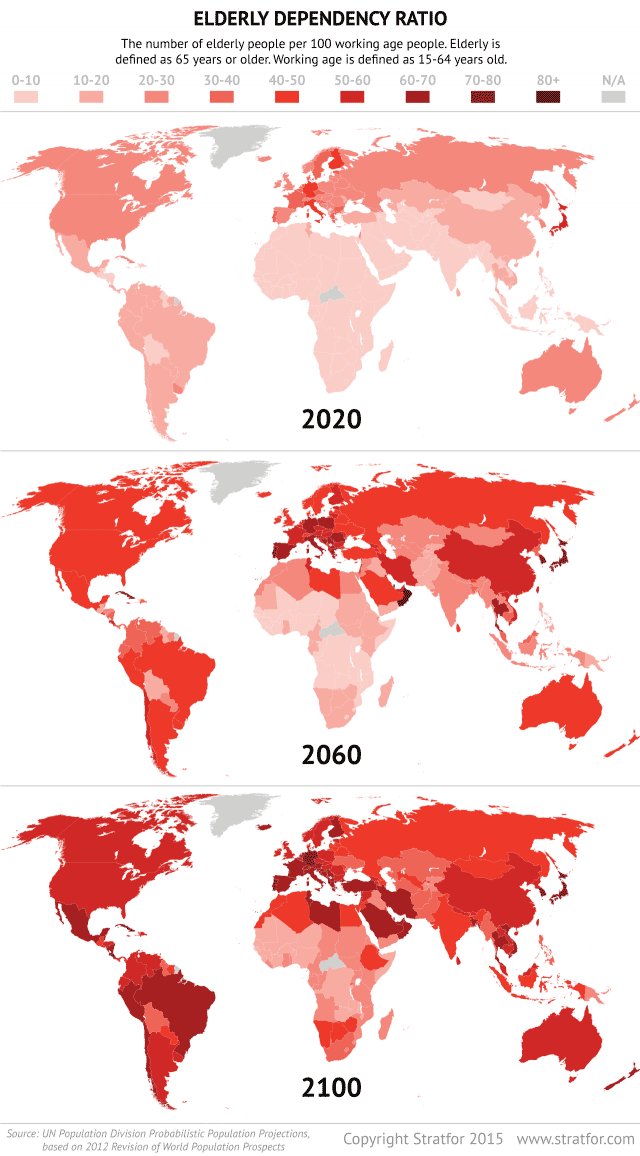

There are those who foresee economic disaster in this process. As someone who was raised in a world that saw the population explosion as leading to economic disaster, I would think that the end of the population boom would be greeted with celebration. But the argument is that the contraction of the population, particularly during the transitional period before the older generations die off, will leave a relatively small number of workers supporting a very large group of retirees, particularly as life expectancy in advanced industrial countries increases. In addition, the debts incurred by the older generation would be left to the smaller, younger generation to pay off. Given this, the expectation is major economic dislocation. In addition, there is the view that a country's political power will contract with the population, based on the assumption that the military force that could be deployed — and paid for — with a smaller population would contract.

The most obvious solution to this problem is immigration. The problem is that Japan and most European countries have severe cultural problems integrating immigrants. The Japanese don't try, for the most part, and the Europeans who have tried — particularly with migrants from the Islamic world — have found it difficult. The United States also has a birthrate for white women at about 1.9, meaning that the Caucasian population is contracting, but the African-American and Hispanic populations compensate for that. In addition, the United States is an efficient manager of immigration, despite current controversies.

[Must Read: Rise of Radical Parties Challenges Eurozone Efficiency]

Two points must be made on immigration. First, the American solution of relying on immigration will mean a substantial change in what has been the historical sore point in American culture: race. The United States can maintain its population only if the white population becomes a minority in the long run. The second point is that some of the historical sources of immigration to the United States, particularly Mexico, are exporting fewer immigrants. As Mexico moves up the economic scale, emigration to the United States will decline. Therefore, the third tier of countries where there is still surplus population will have to be the source for immigrants. Europe and Japan have no viable model for integrating migrants.

The Effects of Population on GDP

But the real question is whether a declining population matters. Assume that there is a smooth downward curve of population, with it decreasing by 20 percent. If the downward curve in gross domestic product matched the downward curve in population, per capita GDP would be unchanged. By this simplest measure, the only way there would be a problem is if GDP fell more than population, or fell completely out of sync with the population, creating negative and positive bubbles. That would be destabilizing.

But there is no reason to think that GDP would fall along with population. The capital base of society, its productive plant as broadly understood, will not dissolve as population declines. Moreover, assume that population fell but GDP fell less — or even grew. Per capita GDP would rise and, by that measure, the population would be more prosperous than before.

One of the key variables mitigating the problem of decreasing population would be continuing advances in technology to increase productivity. We can call this automation or robotics, but growths in individual working productivity have been occurring in all productive environments from the beginning of industrialization, and the rate of growth has been intensifying. Given the smooth and predictable decline in population, there is no reason to believe, at the very least, that GDP would not fall less than population. In other words, with a declining population in advanced industrial societies, even leaving immigration out as a factor, per capita GDP would be expected to grow.

Changes in the Relationship Between Labor and Capital

A declining population would have another and more radical impact. World population was steady until the middle of the 16th century. The rate of growth increased in about 1750 and moved up steadily until the beginning of the 20th century, when it surged. Put another way, beginning with European imperialism and culminating in the 20th century, the population has always been growing. For the past 500 years or so, the population has grown at an increasing rate. That means that throughout the history of modern industrialism and capitalism, there has always been a surplus of labor. There has also been a shortage of capital in the sense that capital was more expensive than labor by equivalent quanta, and given the constant production of more humans, supply tended to depress the price of labor.

For the first time in 500 years, this situation is reversing itself. First, fewer humans are being born, which means the labor force will contract and the price of all sorts of labor will increase. This has never happened before in the history of industrial man. In the past, the scarce essential element has been capital. But now capital, understood in its precise meaning as the means of production, will be in surplus, while labor will be at a premium. The economic plant in place now and created over the next generation will not evaporate. At most, it is underutilized, and that means a decline in the return on capital. Put in terms of the analog, money, it means that we will be entering a period where money will be cheap and labor increasingly expensive.

The only circumstance in which this would not be the case would be a growth in productivity so vast that it would leave labor in surplus. Of course if that happened, then we would be entering a revolutionary situation in which the relationship between labor and income would have to shift. Assuming a more incremental, if intensifying, improvement in productivity, it would still leave surplus on the capital side and a shortage in labor, sufficient to force the price of money down and the price of labor up.

That would mean that in addition to rising per capita GDP, the actual distribution of wealth would shift. We are currently in a period where the accumulation of wealth has shifted dramatically into fewer hands, and the gap between the upper-middle class and the middle class has also widened. If the cost of money declined and the price of labor increased, the wide disparities would shift, and the historical logic of industrial capitalism would be, if not turned on its head, certainly reformulated.

We should also remember that the three inputs into production are land, labor and capital. The value of land, understood in the broader sense of real estate, has been moving in some relationship to population. With a decline in population, the demand for land would contract, lowering the cost of housing and further increasing the value of per capita GDP.

[Read Also: The Raging “Currency Wars” Across Europe]

The path to rough equilibrium will be rocky and fraught with financial crisis. For example, the decline in the value of housing will put the net worth of the middle and upper classes at risk, while adjusting to a world where interest rates are perpetually lower than they were in the first era of capitalism would run counter to expectations and therefore lead financial markets down dark alleys. The mitigating element to this is that the decline in population is transparent and highly predictable. There is time for homeowners, investors and everyone else to adjust their expectations.

This will not be the case in all countries. The middle- and third-tier countries will be experiencing their declines after the advanced countries will have adjusted — a further cause of disequilibrium in the system. And countries such as Russia, where population is declining outside the context of a robust capital infrastructure, will see per capita GDP decline depending on the price of commodities like oil. Populations are falling even where advanced industrialism is not in place, and in areas where only urbanization and a decline of preindustrial agriculture are in place the consequences are severe. There are places with no safety net, and Russia is one of those places.

The argument I am making here is that population decline will significantly transform the functioning of economies, but in the advanced industrial world it will not represent a catastrophe — quite the contrary. Perhaps the most important change will be that where for the past 500 years bankers and financiers have held the upper hand, in a labor-scarce society having pools of labor to broker will be the key. I have no idea what that business model will look like, but I have no doubt that others will figure that out.

Population Decline and the Great Economic Reversal is republished with permission of Stratfor.

Related:

Stratfor's Reva Bhalla on Geopolitical Outlook for 2015