Oil analysts were mostly caught flat-footed by the price decline that began to unfold in June of last year, which has become one of six such drops of greater than 30 percent over the past three decades. Oil price forecasting techniques range from the analysis of futures to sophisticated models incorporating a host of economic variables. Of course, none that we have seen is reliable in the sense of offering precise predictions.

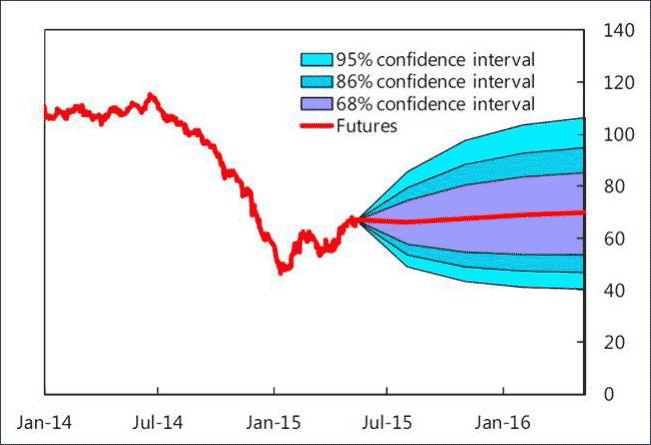

Futures Offer Little Certainty In Predicting Oil Prices

Source: International Monetary Fund

However, not all oil price declines are the same.

They originate from different causes, and have different economic effects. The future path of the price of oil may be less than predictable, but understanding the specific characteristics of the decline that’s in front of us can suggest trends that influence growth, inflation, and other key variables in various economies, from the US to China and the emerging markets.

Global stock markets are being roiled at the moment by psychological fears sparked by the Fed’s apparent timidity in raising rates. In their statement, the FOMC referred to risks they saw “abroad,” and markets quickly took that as a vote of “no confidence” in the global economy. Already spooked by China’s stock market crash, and becoming obsessed with the risk of a Chinese “hard landing,” some market participants read the FOMC’s concern as confirmation that the specter of deflation is about to overtake the global economy, and especially emerging markets.

In that context, some will find it easy to interpret oil’s rocky 15-month price slide as another confirmation that the recovery is coming unglued and the death of the bull is imminent. The price of oil has fallen, according to this reasoning, because demand is collapsing, and demand is collapsing because the expansion is aging and another recession is coming into view. This may be jumping to an erroneous conclusion.

Is That Why the Price Is Falling?

In the past 30 years, there have been 6 oil significant oil price declines (greater than 30 percent):

The time periods when these declines occurred — with their very different geopolitical and economic characteristics — indicate that a variety of forces can be at work to drive oil price declines.

Broadly, there are three such forces:

- Demand shocks related to a broad slowdown in global economic activity;

- Demand shocks related to negative geopolitics in oil-producing regions (i.e., anticipatory demand shocks); and

- Supply shocks.

Sometimes one of these is in play; sometimes two or even all three contribute to an oil price shock.

A World Bank analysis published earlier this year states the obvious. The analysis decomposed the current decline, and reached the conclusion that virtually all of it is due to a supply shock — not to either kind of demand shock.

Scale shows cumulative percentage contribution to price decline

Source: World Bank

From this analysis, the current price decline comes out looking entirely different from the decline that occurred during the Great Recession. In short, if this is true, oil is not the canary in the global economic coal mine.

Is This Interpretation Plausible?

We believe it is. The news alone would warn of oversupply when Saudi Arabia stated months ago that it would increase production by upwards of 2 million barrels per day. What are the components that have contributed to the supply shock underlying the current price decline?

- A long-term trend of greater-than-anticipated supply, especially from US shale producers, Canadian oil sands, and biofuels — corn ethanol in the US, sugar ethanol in Brazil, and biodiesel in Europe;

- The apparent capitulation of OPEC, with the cartel effectively abdicating its role as swing producer, and Saudi Arabia and other significant producers (such as Russia) refusing to get on board with production discipline;

- The unwinding of negative psychology around oil geopolitics, with (for example) Iraqi production suffering less than anticipated, Libyan production higher, and Iranian production coming back into global markets;

A Secular Trend Affecting Supply/Demand Balance

Another trend worth noting is the steady decline in the oil intensity of GDP from the early 1970s to the present. Of course, this graph represents technological change — as technology develops, less oil is required to generate each incremental dollar of GDP growth.

LHS: Oil consumption as percent of total energy consumption.

RHS: Oil consumption relative to real GDP, 1954 = 1.

Source: World Bank

Thus, a confluence of near-term and long-term forces has occurred, and accounts for almost all of the oil price decline experienced over the last 15 months. It’s not a collapse in demand due to the end of an economic cycle; it’s an excess of supply which is due to technological innovation, geopolitical events, and cartel politics.

What Are the Implications?

An analysis of previous declines suggests that they differ in their economic consequences depending on the cause of the decline. The current decline has been driven primarily by a supply shock — amplified by other factors, such as a secular trend of lower oil intensity of GDP, and a near-term trend of US Dollar strength. Such declines have historically had a more significant, more lasting, and more positive effect on global economics than demand-shock declines. As the World Bank noted in its 2015 Global Economic Prospects, “The dominant role of supply factors behind the 2014–2015 drop bodes well for its eventual impact on global [economic] activity. Estimates suggest that a purely supply-driven decline of 45 percent in oil prices could be associated with a 0.7–0.8 percent increase in global GDP over the medium term.”

The Channels of Transmission

If we set aside fears that the price of oil represents evidence for an impending economic downturn — and recognize that on balance, across the global economy, its effect will be positive — then we can look at how different countries will fare.

The decline basically represents a shift in real income from net oil exporters to net oil importers. The overall boost to global GDP comes from the fact that oil exporters tend to save more, and oil importers tend to spend more, so this should translate into stronger global demand.

However, the shock may be more immediate and sharp for producers — particularly for those who are the most fiscally stressed, especially countries like Venezuela, Nigeria, and Russia — while the benefits for importers could be diffuse, and offset by various factors.

Low oil prices in the US, analysts believe, could add 1.25 percent to GDP over 1 to 2 years. However, this doesn’t take into account the relatively large energy footprint in US GDP, employment, and capital markets. Also, as we have seen over the past year, consumers who are getting a tax-cut equivalent will spend if they are optimistic… and save if they are pessimistic about their near-term economic prospects. On balance, then, the implications for the US are mixed, but slightly positive.

The European Union should also be a beneficiary, since crude imports in 2013 averaged 9 a barrel and represented 3 percent of GDP. However, deflationary concerns are weighing heavily on European policy-makers, and deflation could reduce the benefit of cheaper oil for Europe.

Japan is also engaged in a battle against deflation; if Japan’s aggressive monetary stimulus boosts consumers’ willingness to spend and Japanese firms’ willingness to invest, cheaper oil should represent a significant gain for Japanese economic growth.

China will benefit, but only slightly, since oil accounts for only 18 percent of energy consumption, and coal 68 percent. But China is still the world’s second-largest importer, and should see a 0.5 to 1 percent boost in GDP from the oil price decline.

Other emerging-market net oil importers will benefit too, for example, India, South Africa, South Korea, Taiwan, Malaysia and Turkey. A complicating factor for emerging-market economies is that the benefits of cheaper oil do not pass through to consumers as thoroughly, since many of them have subsidy and price-control regimes in place. Therefore the state can capture much of the benefit that would otherwise pass to the local economy. If it deploys that benefit to reduce distorting subsidies, or to strengthen its fiscal position, then its economy would benefit — but that depends on specific policy decisions in particular countries.

Investment implications: Analysis suggests that the sharp decline in the price of oil over the past 15 months is not a demand shock pointing to an imminent turn in the global economic cycle. On the contrary, it is primarily a supply shock, driven by longer-term technological trends, as well as cartel politics and near-term geopolitical events. Similar supply shocks in the past have had relatively enduring, positive effects on global economic growth, particularly on the economies of net oil importers where a lack of subsidies and price controls allows the benefit to be transmitted to consumers and local economies.

For more commentary or information on Guild Investment Management, please go to guildinvestment.com.

Related podcast interviews: