For those who plow the seas either for pleasure or for profit, the element of weather is a constant companion. When plying the ocean, weather can turn any sail into a pleasant memory or a hazardous journey. Mariners approach weather with a spirit of resignation. It just happens. It is beyond human control and there is little we can do about it. Yet as sailors we are subject to its every caprice. Becoming aware of the forces at work within the atmosphere is a large part of seamanship.

Knowledge of atmospheric conditions can determine whether we set sail, remain in port, or if on the seas, button down the hatches. Understanding weather is nothing more than the awareness of the movement and change in the bottom layer of the ocean and the jet stream towering miles above us. Casual sailors may approach the subject with indifference but serious mariners are allowed no such nonchalance. Their lives, the safety of their crew, and the boats they captain are subject to the interchange between the forces of water and air. Their vessels float on top of one sea and at the bottom of another, subject to their buffets and interplay.

Recognizing the importance of weather and atmospheric conditions involves forecasting. Essentially, forecasting is the detection and interpretation of significant changes in atmospheric conditions. In order to accomplish this task sailors use instruments and natural observations in order to deduce subtle trends that will provide a clue to coming events. In good weather you use your radio, eyes, and instruments. In bad weather it is just the reverse. In other words, you use your instruments first because they give you readings of the atmosphere. Next, you use your eyes, observing the sea conditions. Lastly, you use your radio to talk to those on your left and right as they report on storm conditions.

The Barometer – An Essential Tool in Forecasting

One instrument used by mariners and meteorologists is a barometer. Aboard ship, it is the single most important forecasting tool. It allows your eyes to "see" what is happening in the atmosphere. The shape and color of clouds may give you a pretty good indication of what is coming, as long as they are visible. But when they aren't present, the barometer allows you to see what the eyes can't.

A barometer measures atmospheric pressure. What's important to the seaman is being able to gauge the speed of change in atmospheric pressure or how fast the barometer is rising or falling. A falling barometer may indicate a storm on the horizon. A rising barometer may indicate just the opposite, improving weather conditions. When the barometer drops, it indicates a low-pressure system may be approaching. When pressure is low to the surrounding surface area, air from higher-pressure regions rushes in to balance things out. It is this constant balancing act that gives way to weather changes.

Mariners use visual aids such as clouds, swell and sea conditions, and instruments like the barometer to judge whether a storm front is approaching or whether a warm or occluded front is on the way. Weather and seamanship is a lot like stock market analysis. Just as mariners must predict the conditions under which they will sail, so must investors know the conditions under which they invest. Knowing when a storm front is approaching can mean the difference between a smooth or hazardous journey for sailors, or losses and profits for investors.

Bear-O-Metric Readings

As I glance at my stock market barometer, I can't help but notice the drop in barometric pressure. The most visible signs are market volatility. For most of this decade, the stock market moved without as much as a ten percent correction. That changed in August 1997 with the Asian crisis and in 1998 with the Russian debt and Long Term Capital Management Derivative implosion. Since that time, the market has become increasingly volatile. Today volatility is all around us. It can be seen in the major market indexes day to day and even on an intra-day basis. It is noticeable in the price change of individual stocks. It is also visible in the international bourses of Europe and in Asia.

As I glance at my stock market barometer, I can't help but notice the drop in barometric pressure. The most visible signs are market volatility. For most of this decade, the stock market moved without as much as a ten percent correction. That changed in August 1997 with the Asian crisis and in 1998 with the Russian debt and Long Term Capital Management Derivative implosion. Since that time, the market has become increasingly volatile. Today volatility is all around us. It can be seen in the major market indexes day to day and even on an intra-day basis. It is noticeable in the price change of individual stocks. It is also visible in the international bourses of Europe and in Asia.

Occasional Volatility – The First Sign of a Possible Front

Volatility is a common enough characteristic of markets. By itself, it is useless unless combined with other market indicators. Stock market volatility is nothing new. It indicates change and the absence of firm convictions by market participants. Believers in the "Efficient Market Theory" may argue that market volatility is simply the manifestation of quicker and better market information. In the Information Age, investors receive and process information much more quickly and therefore react more quickly. However, one characteristic of volatility is that it is more closely associated with market declines – just as a drop in barometric pressure is often accompanied by an approaching storm front.

Regular Volatility in Tech & Blue Chips Signals "Caution!"

Today's markets go up one day and down the next with increasing regularity. Days on which major indexes rise and fall by greater than 2% are on the increase. The more this happens, the more uncomfortable it becomes for investors. The degree to which this happens is more pronounced with individual stocks. Individual stocks can rise and fall as much as 5% on a daily basis. This phenomenon doesn't just apply to the more speculative breed of stocks. It is even visible in the blue chip sector. Stocks like Procter & Gamble, Ely Lilly, Bausch & Lomb have fallen as much as 40% in a single session on disappointing news. Volatility seems to be associated with and is often the result of some exogenous event. A recent example is the aftermath of Long Term Capital Management's derivative fiasco. When these single events occur, they heighten investor angst and uncertainty. The market swings suggest that investors are over-reacting to news without paying much attention to fundamental details.

Although these exogenous events cannot account for all of the market's volatility, they are symptomatic of the market's mindset. What may actually be occurring is what Professor Robert Shiller calls the "Feedback Loop". In essence he calls it a reaction to a reaction.[1]

Hidden Factors Collide With Volatility

There are other factors that are not so readily apparent or associated with the more obvious explanations of the market's current volatile state. It has to do with the international monetary jet stream. [See Perspectives Part 1] Central banks around the globe have been madly printing money in an effort to stimulate their economies or put out financial fires. The increase in the circulation of money around the globe, especially the dollar, has fed into a credit expansion of epic proportions. That fiat money has primed the international jet stream sloshing in and out of markets at a whim. It is also expanding credit at an unprecedented rate. This expansion of credit has fed into the market with investors making leveraged bets. The amount of leverage in the markets and the mentality of day trading have added a new dimension of volatility that might otherwise not have existed.

Bear-O-Metric Reading #1 Large Price Dislocations

Volatility and credit expansion make way for dangerous markets. Traders large and small are creating unusually large price dislocations. This is one of the first signs that barometric pressure is dropping and a storm front is approaching. It is a wide misnomer that day trading is confined to the realm of the lone day trader. Increasingly, fund managers and institutions are becoming more active in their daily trading/investment activities. With the emphasis on performance, fund managers are moving in and out of sectors on the first hint of good or bad news often reacting in the same way as the individual day trader. You only need to look at volume levels and the turnover of mutual funds to validate this point. Their inordinate price moves alert other investors, which begets a feeding frenzy in the markets. All of this shifting is creating turbulence within the market as it is broadcasted through data terminals, stock screens and charts around the globe.

Bear-O-Metric Reading #2 Index Peaks

Volatility factors alone may not indicate a storm front is on the way. It is the combination of this factor with other indicators that is flashing warning signs. Chief among them is the number of milestones, which have been reached and not surpassed. The following are just a few of the signposts:

DAILY NEW HIGHS PEAKED ON OCTOBER 3,1997

THE ADVANCE-DECLINE TOPPED OUT APRIL 3, 1998

THE DOW JONES TRANSPORTS PEAKED ON MAY 12, 1999

THE DOW INDUSTRIALS PEAKED ON JANUARY 14, 2000

THE NASDAQ HIT A PEAK ON MARCH 10, 2000

THE AMEX TOPPED OUT ON MARCH 23, 2000[2]

The Dow Utility Average and the S&P 500, which had peaked out on January 14th and on March 24th, have recently been surpassed. And yet, we must remember that the S&P 500 has undergone a recent revision of its companies with the addition of more momentum stocks, including such high tech stocks as JDS Uniphase. The Dow Utilities may be responding for other reasons, including a slowdown in the economy, a drop in interest rates, or simply a reaction to the current power crisis in our country.

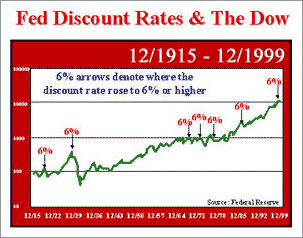

Bear-O-Metric Reading #3 Discount Rate Rise

There are other warning signs, when combined with volatility, which may indicate a gathering storm is approaching. In the past, whenever the discount rate approached 6%, the stock market ran into trouble. Sometimes that trouble was a momentary squall as we saw in 1969 or a major typhoon as in 1929 and in 1973. In every case, when the discount rose to 6% or above, a depressed stock market followed.

There are other warning signs, when combined with volatility, which may indicate a gathering storm is approaching. In the past, whenever the discount rate approached 6%, the stock market ran into trouble. Sometimes that trouble was a momentary squall as we saw in 1969 or a major typhoon as in 1929 and in 1973. In every case, when the discount rose to 6% or above, a depressed stock market followed.

Bear-O-Metric Reading #4 Money Aggregate Drop

Another factor of immediate relevance is the slowdown in the rate of growth in money aggregates. As pointed out in previous articles, [See Storm 1 and Storm 2], there is an implicit relationship that exists between the supply of money in the economy and the direction of stock prices. When the supply of money increases, share prices advance. Conversely, when the rate of money growth slows down, share prices head lower. This is visible in the monetary base at the beginning of the year when the Fed was draining liquidity out of the market as a result of the monetary infusion ahead of Y2K. The lesson here is that money-supply growth and stock market gains move in tandem.

Recently released transcripts of the FOMC July 2000 meeting shows that the Fed has been targeting stock prices since 1994. Whether the Fed chairman calls it "Irrational Exuberance" or the "Wealth Effect" it is obvious what he means. Greenspan has explained on numerous occasions that there is a need to prick the "bubble" in the stock market. Because there is so much debt within the economy, it will be necessary to let the air out of the bubble slowly. The Fed is surely mindful of what happened when the Bank of Japan tried to prick its stock market bubble in 1989 and 1990. The Fed chairman is also cognizant of the Fed's own printing presses which, until recently, have been operating at full throttle.

Recently released transcripts of the FOMC July 2000 meeting shows that the Fed has been targeting stock prices since 1994. Whether the Fed chairman calls it "Irrational Exuberance" or the "Wealth Effect" it is obvious what he means. Greenspan has explained on numerous occasions that there is a need to prick the "bubble" in the stock market. Because there is so much debt within the economy, it will be necessary to let the air out of the bubble slowly. The Fed is surely mindful of what happened when the Bank of Japan tried to prick its stock market bubble in 1989 and 1990. The Fed chairman is also cognizant of the Fed's own printing presses which, until recently, have been operating at full throttle.

Streetwise Bullishness – A Myriad of Paradoxes

There are other signposts that spell future market difficulties. Among them are the numerous paradoxes that exist within the market itself. There is a sharp contrast between Wall Street's perpetual bullishness and the malaise among the Street's institutional customers. After falling short of stock market predictions for the first part of the year, the Street has upgraded market targets for the second half of the year. The estimates that fell short during the first half of the year have simply been transferred to the second half. Everyone is counting on a strong second half and an election year bounce. In greater numbers we are seeing the disparity between company estimates and analysts' estimates, which tend to look better beyond the horizon.

There are other paradoxes such as the direction of the economy and what is happening on the corporate earnings front. More and more companies are warning the Street of profit difficulties. The bulls are counting on strong earnings to bail out the markets, but that story is becoming less compelling with each passing month. After all, if the economy slows down, would it not be logical that corporate profits slow down with it?

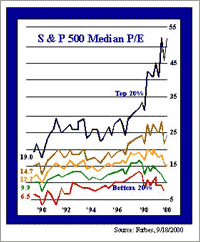

A final paradox is the breakdown of standard and accepted technical and fundamental indicators. Neither indicator has been helpful in gauging the market's future direction. It is as if they were actually malfunctioning. Try explaining a company growing at 20-30% a year that is selling at 200-300 times earnings! For that matter, whether you look at P/E ratios, dividend yields, or price-to-book ratios, nothing apparently makes sense today. Explanations for these indicator trends are summed up in catchy phrases of the day like "It's different this time.", "It's a new era" or "It's a new economy".

Market Fundamentals Out of Whack

Much has been said about the market's fundamentals being out of touch with reality. As these graphs indicate, whether looking at P/E ratios or dividend yields, the current market is at extreme levels. What is even more apparent is how far the market would have to fall to get back to normal levels. The S&P 500 currently trades at 29 times this year's earnings, equating to an earnings yield of 3%. What's more, the S&P trades at 93 times dividends. In other words, investors are willing to pay to receive in dividends. The bullish arguments for low dividends and expensive price-earnings multiples are similar to previous market peaks. Dividends are low because companies are using cash to buy back their stock or invest in acquisitions. Price/Earnings multiples are high because investors are apparently willing to pay more for superb earnings growth.

Much has been said about the market's fundamentals being out of touch with reality. As these graphs indicate, whether looking at P/E ratios or dividend yields, the current market is at extreme levels. What is even more apparent is how far the market would have to fall to get back to normal levels. The S&P 500 currently trades at 29 times this year's earnings, equating to an earnings yield of 3%. What's more, the S&P trades at 93 times dividends. In other words, investors are willing to pay to receive in dividends. The bullish arguments for low dividends and expensive price-earnings multiples are similar to previous market peaks. Dividends are low because companies are using cash to buy back their stock or invest in acquisitions. Price/Earnings multiples are high because investors are apparently willing to pay more for superb earnings growth.

As Warren Buffet argued in his November 1999 Fortune article, earnings during this economic recovery have been sub-par in comparison to previous economic recoveries.[3] In fact not only have earnings been below normal (see graph) but they were temporarily enhanced by a reduction in interest rates during the early part of the decade. Corporations refinanced much of their debt as interest rates declined. This bottom line refinement gave a temporary boost to earnings since refinancing reduced interest expense. Reductions in corporate tax rates and the lengthening of depreciation periods also enhanced corporate profits. However, these were one-time events unlikely to happen in succession again. As Buffet so convincingly argues, the temporary boost to earnings didn't come from the operating side of the business.

As Warren Buffet argued in his November 1999 Fortune article, earnings during this economic recovery have been sub-par in comparison to previous economic recoveries.[3] In fact not only have earnings been below normal (see graph) but they were temporarily enhanced by a reduction in interest rates during the early part of the decade. Corporations refinanced much of their debt as interest rates declined. This bottom line refinement gave a temporary boost to earnings since refinancing reduced interest expense. Reductions in corporate tax rates and the lengthening of depreciation periods also enhanced corporate profits. However, these were one-time events unlikely to happen in succession again. As Buffet so convincingly argues, the temporary boost to earnings didn't come from the operating side of the business.

This enhancement technique is easily visible when one examines the income statements of many of today's market leaders from Coca-Cola, IBM, and Hewlett Packard to high tech titans, Microsoft and Intel. Wall Street and corporate management have been playing a game with earnings (See The Earnings Game for more details of this argument). From earnings charges, issuing and selling options on their own stock to booking capital gains as operating profits, earnings have been spruced up to meet Wall Street and investor expectations.[4] The idea of super earnings doesn't stand up to scrutiny. That is not to say that there haven't been many companies who are growing earnings at above normal rates. But many of those who do produce above-average growth rates are selling at earnings multiples that don't hold up to discounting value mechanisms.

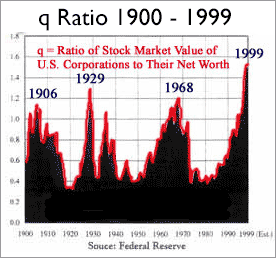

The Importance of q

Perhaps the most telling measure of extreme value in this market is a measure called the q Ratio. As pointed out in Part 1 An Introduction, q Ratio measures the relationship of the net worth of the corporate sector to the total value of the stock market. It doesn't wander or change as frequently as P/E ratios, which can change rapidly with a sudden change in earnings due to a write-off. q Ratio tends to be mean-reverting. Using q can't tell you which stocks are over or under-valued, so many on Wall Street ignore the ratio. What q does measure is whether the markets as a whole are under or over-valued. Its value is that it alerts investors to periods of market extremes. It sends a signal in much the same way as a barometer. It can tell you when the risk of a storm is approaching. As the q Ratio Chart indicates, not since 1929 and the late 1960's have q Ratios been this high.

Perhaps the most telling measure of extreme value in this market is a measure called the q Ratio. As pointed out in Part 1 An Introduction, q Ratio measures the relationship of the net worth of the corporate sector to the total value of the stock market. It doesn't wander or change as frequently as P/E ratios, which can change rapidly with a sudden change in earnings due to a write-off. q Ratio tends to be mean-reverting. Using q can't tell you which stocks are over or under-valued, so many on Wall Street ignore the ratio. What q does measure is whether the markets as a whole are under or over-valued. Its value is that it alerts investors to periods of market extremes. It sends a signal in much the same way as a barometer. It can tell you when the risk of a storm is approaching. As the q Ratio Chart indicates, not since 1929 and the late 1960's have q Ratios been this high.

These charts indicate that investors are placing greater emphasis on capital appreciation versus tangible returns like dividends. During the vast majority of this century, dividends supplied most of the return. However, in this bull market, which began in August of 1982, investors have placed greater value on capital appreciation, especially since 1995. Capital values fluctuate much more than dividends. This greater reliance on capital gains has served to make the markets much more volatile.

Another observation from reviewing these charts is that there are extended periods of time when stock prices were falling. In 1906, 1929, and 1968 markets declined for 15, 25, and 15 years respectively. This means that half of this century has been characterized as a bear market. These bear markets directly followed a peak in q. The q Ratio defines risk, something investors have been ignoring. In fact, people have become passé about risk and returns. Investors' expectations are much higher today and they don't know what it means to lose heavily. These concerns prompted the Vanguard group to conduct a survey among its investors on general market knowledge and risk factors. The mean score was 37%. Clearly much of what passes as investing today would be more characterized as gambling.

Technical indicators have been just as troublesome as the fundamentals. Breadth, which measures the number of shares advancing or declining, has been terrible. Overbought and oversold conditions have often been conflicting, and moving averages have been useless. It is very difficult to make a positive case for the market based on technical indicators. Money flows into the market remain positive but that fact alone doesn't make a strong case for a market to advance. The obvious conclusion is that we remain in a high churning market where swarms of money rotate in and out of sectors like the dance of the honeybees.

Antitrust Moves Demonstrate Outside Forces at Work

From a contrarian viewpoint, there are many weather signs against this market. One troublesome trend is the government's recent antitrust suits against companies such as Microsoft. Bob Prechter, President of Elliot Wave International, has made a strong case that the government's antitrust suits come near stock market peaks.[5]

History points to numerous examples of past market cycles characterized by government attacks against the dominant companies of the era. In 1906, President Roosevelt brought a suit against Rockefeller's Standard Oil Trust that culminated in the break-up of Rockefeller's company. In 1930, shortly after the October crash of the previous year, the antitrust division brought a suit against RCA, the success story of the 1920's bull market. In the late 1960's after the market had topped out, suits were filed against IBM and action was taken against Procter & Gamble ordering the company to divest itself of Clorox.

In today's market, after various market milestones have been reached and not surpassed, the Justice Department's Antitrust Division is busy again attacking the dominant success stories of the era. The Antitrust Division under Clinton is currently attacking Microsoft, Visa and Master Card, as well as blocking mergers of WorldCom and Sprint. In the new science of Socionomics,[6] Prechter argues convincingly that the direction of causality is the opposite of what is generally assumed. To quote Prechter, "Politics do not govern the stock market; the social mood as reflected by the stock market trends governs politics." Bob argues that Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson's evangelical crusade is the by-product of a passion born of the passing of a social mood peak. According to Prechter, major antitrust suits coincide consistently with the major stock market tops.

In today's market, after various market milestones have been reached and not surpassed, the Justice Department's Antitrust Division is busy again attacking the dominant success stories of the era. The Antitrust Division under Clinton is currently attacking Microsoft, Visa and Master Card, as well as blocking mergers of WorldCom and Sprint. In the new science of Socionomics,[6] Prechter argues convincingly that the direction of causality is the opposite of what is generally assumed. To quote Prechter, "Politics do not govern the stock market; the social mood as reflected by the stock market trends governs politics." Bob argues that Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson's evangelical crusade is the by-product of a passion born of the passing of a social mood peak. According to Prechter, major antitrust suits coincide consistently with the major stock market tops.

Quality & Credibility Matter

The bulls keep arguing persuasively that earnings will bail the market out of its present difficulties. But closer scrutiny of the bulls' arguments leaves much to be desired. Chief among them in my estimation is the quality of earnings and the credibility of analysts' estimates - subjects that require closer examination.

The Earnings Gauge Is Dropping

Much of the hype over the future direction of the market this year has been based on earnings. A projected higher earnings in the technology sector during the fourth quarter is the reason Wall Street feels that the markets will head higher by year-end. Evidence also suggests that on balance, election years are favorable to the financial markets. The Fed usually stands pat during the fall campaign while government incumbents are busy handing out pork to gain favor with the voters.

Recent evidence suggests that more companies within the S&P 500 are having difficulty meeting their earnings estimates. It stands to reason that if the economy slows down so will corporate profits. Warren Buffet has made a strong case for why the markets will have difficulty producing strong returns in the next decade.[7]

One reason is that you can't have corporate earnings in the aggregate growing faster than the economy. You can't have economic growth of 3-4% and corporate earnings growth of 20%. Mathematically it just doesn't work out.

Another reason Buffet is doubtful of Wall Street's bullish arguments is that corporate profits during this last economic expansion have been sub-par in comparison to previous economic expansions. The rise in profits has had more to due with financial engineering than with real corporate profitability. (See The Earnings Game).

Tech Turmoil

A good example of what is going on the earnings front is the most recent earnings reports for a few technology stalwarts and the deterioration of earnings at companies such as DuPont, Procter & Gamble, Gillette, Clorox and other consumer growth companies. For example, the nice rally that began in the Nasdaq in July was triggered by Yahoo, which beat analysts' estimates by 1 cent. Buried in the report was the fact that Yahoo's market share of U.S. advertising declined in the first quarter from a year ago. The company's advertising has been dependent on a lot of Dot Com companies whose burn rate jeopardized future advertising revenues. Yahoo rose 26% after the report and has recently been trading at 341 times earnings. Analysis of the company's earnings and growth rate would have to accelerate and market value would have to balloon to about 8 billion by 2010 to justify it's current market capitalization.[8] There are only three companies with market caps this big: GE, Intel and Cisco.

Trouble With the Big Guns

Other examples of questionable earnings are found in recent reports from Microsoft, Intel and Hewlett Packard. Intel reported second quarter income of .5 billion, up 98% from last year, and up 16% from the company's first quarter. To make those earnings, Intel included interest and other income of .3 billion - most of which came from taking profits on the company's technology stock holdings. In reality, most of Intel's profits came from capital gains resulting from stock sales as opposed to operating earnings.[9]

Microsoft also met analyst's estimates for the company's fourth quarter ending June 30th. The company reported profits of .41 billion in comparison to profits of .2 billion, in the same quarter a year ago. Revenue grew at a snail's pace from .76 billion to .8 billion. Included in those earnings, the biggest gain came from investments, which more than doubled to .13 billion from 5 million a year ago.[10]

In the case of both of these two technology giants, the biggest part of their current profits came from capital gains on investments rather than from the core businesses. This finagling is similar to what Coca Cola did under the company's last president. Coke was able to meet its target of 15% earnings growth by buying back stock and booking capital gains from selling its interest in bottling companies to a related subsidiary of the company.

Hewlett Packard shares rose a day after beating analyst's estimates for the latest quarter. The profit gains mainly came from cost-cutting efforts, a lower tax rate, and gains from stock sales. The stock rallied on the initial news. It then plunged the following day when the details of earnings were released.[11]

Performance Pressure Front

As investors look deeper, they will begin to find that financial engineering is playing a greater part in companies meeting Wall Street estimates. The pressure to perform is creating tremendous stress on corporate management to reach beyond operations to meet investor expectations. Companies are turning more and more to accounting gimmickry and balance sheet manipulations to meet these expectations. The consequence of falling short can devastate a company's stock price. Examples of earnings bombshells are everywhere. They range from Clorox, Procter & Gamble, Dupont, to more recently Bausch & Lomb whose stock plunged 36% after announcing a slowdown in profits. The company fired their President Carl Sassano for making that mistake. Next Level Communications stock fell 54% after a Lehman Brothers analyst said another company might reduce purchases from the phone equipment maker.[12]

Redefining Earnings – Depends on What Your Definition of "Is" Is

Wall Street knows that meeting high expectations for earnings growth is making it harder for companies to deliver. To counter this trend, companies and securities analysts are making a big push to bury earnings as we have generally known them. Wall Street wants to divert investors' attention away from the historical bottom line, which has always meant net income or earnings per share. Today's trend on the Street is moving towards multiple definitions of earnings. In other words, instead of one bottom line, there may be two. It all depends on whatever looks best. It reminds me of the commercial jingle, "Have it your way!" Today's definition of earnings may be cash earnings before interest, depreciation and amortization. The idea that the Accounting Standards Board or the government would allow companies to inflate their earnings with an accounting maneuver defies comprehension. The only thing that makes sense to me is the concept that perpetuating the bull market for as long as possible benefits Wall Street, companies and the government. In the future, investors will need to be more careful in their investment selections based on earnings. Earnings may depend on what your definition of earnings "is". [See "The Earnings Game"]

Redefining a Great Buy

Investors are increasingly being asked to buy into stocks without any rationale other than stories, rumors, and estimates. Fundamentals have been thrown out the window. What is important is the hype bombarding investors everywhere they look from financial networks, newsletters, and magazines to chat rooms on the web. Much of the pyramid of speculation in our financial markets today depends on the public's belief in continued prosperity and the expectation that the good times will only get better. Hence, the justification for paying even higher prices for stocks.

Redefining History

It is becoming one of the intellectual axioms of our era. No longer do we see any clear distinction between works of fiction and non-fiction. In this decade the new dominate theory within the humanities asserts that it is no longer possible to tell the truth about the past or to benefit from the knowledge of history. The new historical school of thought being taught on university campuses proclaims that you can only understand history through the prism of your own culture. The result is that historians, literary critics and pundits are now writing their own versions of history. Facts no longer count. The result is that the social science departments at universities have abandoned objectivity and truth to political relativism. It is obvious that this new school of thought has carried over into the financial markets.[13]

New Wave Barometer

This new school of thought originated in France with the poststructuralist theories of the French philosopher Jacques Derrida and the Cambridge University Professor, Quentin Skinner. It has found its most fertile soil in the American university system. The consequence has been the explosion of cultural relativism or political correctness. It can be clearly seen operating in our financial markets. The denizens of Wall Street daily proclaim the irrelevance of standard market benchmarks such as P/E ratios, dividend yields, and price-to-book ratios. Even in the area of growth investing, classic measures of value – such as price-to-sales ratios or PEG ratios – are ignored. The rumor, the hot tip, the latest story, and hype have replaced them. Facts have become less important – they have been replaced by analysts' estimates.

New Wave Weatherman: The Wall Street Analyst – "We Are the Real Story"

Analyst's estimates are focusing investor attention away from what is really happening on the corporate earnings front. The real story has become the analysts, not the companies or their earnings. The financial media has become preoccupied with analysts' estimates; while investors have become obsessed with market gurus that borders on the occult. The analysts have assumed the status of rock stars. Rather than performing real analysis on companies, analysts have become the corporate equivalent of pitchmen for the firms' stock offerings. In a sense, analysts have become rainmakers rather than researchers in recent years with the advent of financial channels and the Internet. Their job is to help their firms win and keep investment-banking clients and keep the brokerage firm's distribution channel humming. On a personal note, I have to sit and watch a portion of these morning financial shows. Why? Because I know my clients are watching and are going to call with buy or sell orders based on the morning's pitch.

Conflicts of Interest

According to a recent report in Fortune, analysts made 33,169 buy recommendations last year.[14] This stands in contrast to only 125 sell recommendations. With nearly 2,200 professionals covering over 6,000 companies, only 125 recommendations were sells! According to Wall Street, "Everything is a buy". It is apparent that the problem stems from conflicts of interest. At one time, the research side of a firm was separate from the investment-banking side. Now they are the grease that makes the engine turn. With the loss of fixed commissions and the advent of on-line trading, the most profitable side of Wall Street is the investment-banking business. Firms can make as much as 7% on the gross offering proceeds of initial public offering (IPO) or in the case of a secondary offering, almost as much.

Reading Between the Lines

The result of this conflict of interest is the preponderance of glowing research reports coming from Wall Street. It is becoming more difficult for investors to discern the truth. The financial media hasn't made things easier. The networks are after ratings because ratings drive advertising revenues. So viewers are subject to a constant parade of analysts and fund managers who are anxious to plug their latest stock, mutual fund, or pitch a new IPO. Absent from these discussions is a full disclosure of conflicts of interests. The analyst's firm may be the underwriter on the stock being promoted or his firm may be a market maker or unloading their position in the stock.

One major investment banking firm went on to promote a particular stock with a strong buy recommendation. The company had been the managing underwriter for the company's initial public offering. While the investment banking firm was promoting its buy recommendation, at the same time, it was unloading more than half of its stake in the company. The stock plunged more than 85% from its high set back in January of this year. You would never know from watching the financial networks that there was anything to be concerned about such as market valuations, deteriorating profits, or sky rocketing debt levels. On Wall Street and on the networks it's always a sunny day.[15]

Hype & Promotion Rule the Day

In many ways, the role of Wall Street and the media have served to perpetuate and inflate the current stock market bubble. What is presented as analysis and reporting these days is nothing more than hype and promotion. There is little done in the way of warning investors of the dangers of the current mania in the stock market. Several financial networks feature weather reports as part of their financial broadcast. The meteorologist reports storm and hurricane warnings, and even the drop in barometric pressure, but these warnings are completely absent from the financial broadcast side of the program.

Remembering History – The Investor's Weather Almanac

What is going on today in this country is reminiscent of similar events that occurred earlier in the 18th century in France. A Scottish dandy had worked his way into becoming France's financial minister based on his scheme to bail out the French government of its debts by issuing paper money instead of coin. John Law's plan to substitute paper money for gold and silver coin became the forerunner of today's central banks. The scheme soon gave way to the government's desire to print unlimited amounts of money to pay its bills and carry on the lavish lifestyles at court. The extra money that was printed worked its way into the economy and ended up fueling a stock market bubble.

Law's Mississippi Company is the equivalent of some of today's Internet stocks. The King, the nobles and the general public kept bidding up the shares of the company stock thereby creating fabulous wealth for many of the initial insiders. The wider public had never before taken part, nor had they seen such rapid rises of wealth on such a scale. Like gluttons most investors accepted the opportunity to gorge themselves without thinking about the consequences of their actions. The huge increase in share prices was founded on little more than hype. The expanded money supply was unthinkably brushed aside. The question of what underpinned these paper fortunes had been dangerously ignored. The share price had been boosted on its upward trajectory by the ease with which money could be printed or borrowed by Law's central bank. Law's scheme eventually fell apart and led to disaster for investors and the country.[16]

What happened back in 18th century France is similar to what is happening in our markets today. The parabolic gains in our financial market are the result of the expansion of money and credit in our economy. There is very little said about the Fed's pedal to the metal approach to expanding the nation's money supply or the mushroom of credit at the consumer and corporate level. Very few investors or commentators spend much time looking at corporate balance sheets or income statements. Much of today's buying is based on hype and little else.

A Storm Is Brewing – Bear-O-Metric Pressure Is Dropping

It is not hard to see that trouble is brewing in the monetary jet stream that hovers above the markets and travels around the globe. The barometer is dropping and it spells trouble ahead for the financial markets. To the untrained eye, there is obviously something going on. Very few investors are heeding the barometer's warnings. Optimistically, I would hope that the barometer's reading is nothing more than an indication of a momentary squall. However, there are too many other signs that indicate otherwise.

To gauge whether to set sail or stay in port, mariners use a combination of tools to assess the trends that will provide a clue to coming events. They range from visual observations of clouds, swells and sea conditions to barometric readings. The barometer is most useful when there are no clouds on the horizon. There are no "sensual" indicators, only those foretold by the dropping barometer. The barometer allows you to see what the eyes can't see in the atmosphere.

Today there are many visible signs of trouble. Market volatility and the breakdown of fundamental and technical indicators are only a few. There are other signs, which are subtler and not visible to the human eye, below the surface. They show up in bear-o-metric readings of the nation's money supply, credit expansion and the breakdown of corporate earnings. With all of these readings, we know that a storm is coming. The question is, "What kind will it be?"

As a personal money manager entrusted with the financial well being of my clients, the financial barometer tells me to proceed cautiously. With an eye on current market readings and knowledge of market history, I tend to monitor my client holdings carefully. I have received hundreds of responses to my prior installments on "The Perfect Financial Storm?". Many ask advice on what to do or how to position themselves in today's market. My advice — get out of debt. With the tremendous rise in national, corporate and personal debt, irreparable damage could be done to personal income budgets, college education funding or a quality retirement lifestyle. This is not the time to "bet the ranch" on a hot pick.

Over the past several months, I have seen a growing flight to quality in stock market investing. It is time to take a long, hard look at our holdings. A key question to ask is this, "Will they hold up in a dramatic drop in bear-o-metric pressure?"

It's Time to Bottom-Fish—Lower P/E Stocks at Bargain Prices

I am not suggesting that it is time to pull out of all stock investments. In fact, in this stealth bear market, many stocks have fallen as much as 75% — a point which makes them an attractive investment. The lesson here, if investing in stocks, is that you do so at attractive values. Buying popular high-fliers can be the quickest way to devastate one's wealth. In fact, in today's investment market, the most attractive investment opportunities may lie in bottom fishing. Today, there are many high-quality companies that are growing their earnings at the same rate as the market leaders. The difference is found in their P/E ratios.

I am not suggesting that it is time to pull out of all stock investments. In fact, in this stealth bear market, many stocks have fallen as much as 75% — a point which makes them an attractive investment. The lesson here, if investing in stocks, is that you do so at attractive values. Buying popular high-fliers can be the quickest way to devastate one's wealth. In fact, in today's investment market, the most attractive investment opportunities may lie in bottom fishing. Today, there are many high-quality companies that are growing their earnings at the same rate as the market leaders. The difference is found in their P/E ratios.

On the ocean, when storm conditions are approaching, sailors reduce sail to help keep the boat more manageable under heavy winds and seas. Fishermen drop their paravanes and birds into the water to stabilize the boat against tumultuous seas. In my estimation, the market's barometer is telling me it's time to prepare the paravanes.

References:

[1] Professor Robert Shiller, Irrational Exuberance

[2] Richard Russell, Dow Theory Letter, Letter #1303, 7/6/2000

[3] Fortune, November 22, 1999, "Mr. Buffet On The Stockmarket"

[4] berkshirehathaway.com, Chairman's Letter, 1998

[5] Robert Prechter, The Elliott Wave Theorist, "A Socionomic Perspective on the Microsoft Case", May 2000

[6] Robert R. Prechter, Jr., The Wave Principle of Human Social Behavior and the New Science of Socionomics

[7] Fortune, November 22, 1999, "Mr. Buffet On The Stockmarket"

[8] Bloomberg News, "Yahoo's Analyst Ratings Roster", August 17, 2000

[9] Wall Street Journal, "Intel Profits Beat Estimates," July 18, 2000

[10] Wall Street Journal, "Microsoft Beats Forecasts," July 18, 2000

[11] Bloomberg News, "Hewlett Packard Falls 11% On Analysts Sales Concerns," August 17, 2000

[12] Bloomberg News, "Next Level Shares Plunge After Lehman Cuts Ratings," August 24, 2000

[13] Keith Windschuttle, The Killing of History, The Free Press, New York, 2000

[14] Fortune, "A Whole New Ballgame," July 24, 2000

[15] Bloomberg News, "Goldman Sells Free Market Shares While Recommending Others Buy," June 29, 2000

[16] Charles MacKay, LL.D, Extraordinary Popular Delusions and The Madness of Crowds, Templeton, 2000

Book Reading Recommendations:

- The Fortune Tellers: Inside Wall Street's Game of Money, Media and Manipulation by Howard Kurtz

- Irrational Exuberance by Robert J. Shiller

- Irrational Exuberance and the Illusion of Prosperity by Don DeVitto

- The Wave Principle of Human Social Behavior and the New Science of Socionomics by Robert R. Prechter, Jr.

- Riding the Bear: Reap Huge Gains by Recognizing a Bear or Bull Market by Sy Harding