- BEGUN, THE CURRENCY WARS HAVE: For years, the US has been pressuring China to allow its currency to appreciate. But Japan’s unilateral intervention in the foreign exchange market in September represents the opening of a new front in an escalating global currency war. Indeed, this event may be the trigger which sets off a series of similar actions elsewhere. Past episodes of global currency devaluation, such as in the 1970s and 1930s, have always led to increases in global commodity prices, even amidst relatively weak economic growth.

- WHEN ONLY A MUCH WEAKER DOLLAR WILL DO: Absent widespread asset price deflation and debt restructuring that would be resisted at all costs by the US Fed and Treasury, the US economy can only return to sustainable growth when incomes catch up to existing asset prices. This requires substantial wage inflation. Amidst structurally high unemployment, the only way to generate wage inflation is via a weaker dollar, implying higher commodity prices. But how far would the dollar need to fall to push wages up by enough to bring incomes into line with current asset prices?

BEGUN, THE CURRENCY WARS HAVE

For several years now the US and some other countries have been pressuring China to allow its exchange rate to appreciate, thereby making Chinese goods relatively less competitive in the global economy and, so the thinking goes, assisting the US and other heavily indebted economies with a necessary economic rebalancing away from consumption and imports toward investment and exports. In September, the US House of Representatives began formal debate on a proposed measure to label China a “currency manipulator” and impose a broad range of trade restrictions on Chinese goods. But as this dispute escalates, there are other important developments in currency policy taking place around the globe with potentially highly destabilising and economically destructive consequences.

It is a common delusion that major exchange rates, such as those between the dollar, the euro, the yen and the pound sterling, are free-floating. The cause of this may be that FX rates appear to move up or down on a regular basis in seemingly random fashion, or that mainstream economic textbooks generally make this claim. But it is not true. Japan demonstrated as much in September, when the Bank of Japan, under the instructions of the Ministry of Finance, sold yen into the foreign exchange market, pushing up the USD/JPY exchange rate from 83 to nearly 86, a 4% move, in a single day. According to Japanese authorities, the yen had become too strong to remain compatible with their economic objectives of maintaining positive economic growth and preventing deflation.1

Policymakers elsewhere were quick to condemn Japan’s unilateral action. One prominent vocal critic was Jean-Claude Juncker, Prime Minister of Luxembourg and, more importantly, the Chairman of the “Eurogroup”: the council of euro-area finance ministers responsible for coordinating economic and policy. As such, in matters of currency policy, Mr Juncker’s role is comparable to that of the US Treasury Secretary or Japanese Minister of Finance.

A possible concern shared by Mr Juncker and his Eurogroup colleagues is that, should Japan continue to intervene to weaken the yen, then the euro-area will become less competitive in world export markets, in particular for the machinery and other capital goods in which there is intense competition between European and Japanese firms.

Indeed, at an exchange rate of 1.35 to the dollar, the euro is at a lofty level relative to history. Yet at 113 versus the yen, the euro is in fact quite weak. Prior to the financial crisis in 2008, the EUR/JPY exchange rate reached nearly 170. Thus over the past two years euro-area exports have become much more competitive relative to Japanese. So why should Mr Juncker be complaining so loudly if Japan is now attempting to prevent further yen strength?

It could be that he is concerned more by what unilateral currency intervention represents in principle, rather than what it in fact achieves in practice. Consider: What if not only Japan but other countries facing weak growth and potentially deflation begin to intervene? Well, many countries are already doing so. China manages its exchange rate versus the dollar. So do all other Asian countries in varying degrees. Brazil buys dollars on a regular basis to keep their currency, the real, at a targeted level.2 Russia does the same with the ruble. The risk is that, by acting unilaterally, Japan has escalated what is already a “cold” currency war, greatly increasing the chances that it becomes “hot”, with countries not seeking merely to maintain a given exchange rate but to devalue faster and by more than others in a, “beggar thy neighbour” policy.

Currency wars might thus appear to be zero-sum. But this is true only up to a point. For if all countries intervene to weaken their currencies in equal measure, then no country succeeds in devaluing versus the others. As such, they might then resort to raising trade barriers or enacting currency controls which restrict the flow of capital across borders. These sorts of actions cause substantial economic damage however and are thus hugely counterproductive. The 1930s were characterised by, among other things, currency devaluation, capital controls and rising trade barriers such as the infamous “Smoot-Hawley” tariff.

Currency wars might thus appear to be zero-sum. But this is true only up to a point. For if all countries intervene to weaken their currencies in equal measure, then no country succeeds in devaluing versus the others. As such, they might then resort to raising trade barriers or enacting currency controls which restrict the flow of capital across borders. These sorts of actions cause substantial economic damage however and are thus hugely counterproductive. The 1930s were characterised by, among other things, currency devaluation, capital controls and rising trade barriers such as the infamous “Smoot-Hawley” tariff.

While potentially growth negative for the global economy, currency and trade wars can, however, contribute to rising price inflation. Why? Well, the weapons of currency wars are the printing presses. The more you print, the more you can weaken your currency, or at a minimum prevent it from rising. He who prints most, devalues most and “wins”. But if all print in equal measure, exchange rates don’t move, but the global money supply soars. As such, currency wars don’t stimulate real economic growth–indeed they are much more likely to weaken it–they stimulate only nominal growth, that is, inflation. The net result is most likely to be a global “stagflation”.

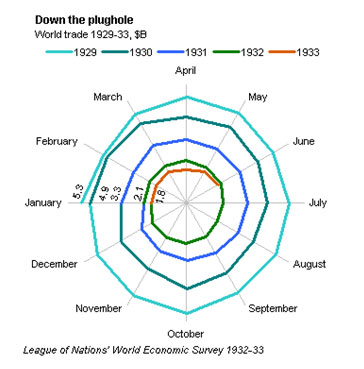

The economically devastating effects of currency and trade wars can be seen in the chart to the right, which shows the dramatic contraction in world trade that took place in the early 1930s. Now it is easy to mix up cause and effect here. It is perfectly normal for trade to contract when growth contracts. But when trade barriers are raised they become the cause of contraction rather than the effect. The Smoot-Hawley tariff was enacted in June 1930 but had already passed the US House of Representatives in May 1929, well prior to the stock market crash in October that year. It is thus rightly considered a cause rather than effect of the Great Depression. Nor was it an isolated act. Among other countries, Canada, the largest US trading partner, retaliated by raising tariffs on US goods. Great Britain devalued the pound sterling in 1931. Japan did the same with the yen that year. In 1934, the US devalued the dollar. These were all major acts in a prolonged and devastating currency and trade war.

Some might argue based on the 1930s US experience that currency and trade wars should lead to deflationary depression rather than stagflation. But the US experienced deflation, visible in falling commodity and consumer prices, only as long as it kept the dollar fixed to gold at .67/oz. Following the 1934 dollar devaluation to /oz, the deflation was over. Commodity prices generally moved sideways rather than lower in the second half of the decade. Growth remained weak, to be sure, but that was not the result of deflation but, rather, structural economic weakness related to the unprecedented level of government micromanagement in the economy, with all manner of wage and price controls and, of course, counterproductive global trade barriers such as Smoot-Hawley.

As neither the world nor the US are on a gold (or silver, or other) standard, currency and trade wars are thus likely to translate directly into stagflationary pressures, with economic growth generally weaker and commodity prices generally higher. This is a horrible set of conditions for corporate profit growth, which is going to get squeezed between rising raw material costs on the one side and poor overall revenue growth on the other. The 1970s are instructive in this regard. The CRB broad commodity index trebled between 1971–when the US devalued and went off the gold standard–and 1981, whereas the S&P index rose by a mere 35%. The lesson for investors today, as the currency wars escalate, should be obvious.

WHEN ONLY A MUCH WEAKER DOLLAR WILL DO

It is sometimes challenging to make sense of economic policymakers’ frequently convoluted and occasionally obfuscating language. There are times, however, when they say what they mean rather clearly. This the Fed did in its September policy meeting statement. While these statements normally contain quite standard language that does not change materially meeting to meeting, last month was an important exception. The Fed chose to add some text which, when placed in context, implies that the Fed now has a bias to apply more unconventional stimulus to the economy. Here is the relevant excerpt:

Measures of underlying inflation are currently at levels somewhat below those the Committee judges most consistent, over the longer run, with its mandate to promote maximum employment and price stability. With substantial resource slack continuing to restrain cost pressures and longer-term inflation expectations stable, inflation is likely to remain subdued for some time before rising to levels the Committee considers consistent with its mandate.3

Now if inflation is too low and is likely to remain too low for “some time”, then the Fed clearly has a bias to do what it can to try and expedite a rise in inflation. But with policy rates already near zero and the Fed already preventing a natural shrinkage of its balance sheet as securities holdings mature, all that is left is for the Fed to reach further into its toolkit of unconventional policies.

We have examined the Fed’s various unconventional policy tools in previous Amphora Reports and concluded that, absent a decline in the dollar and/or rise in commodity prices, the Fed is not going to succeed in increasing the rate of price inflation. This is because the money and credit transmission mechanism is the US is broken due to a weak financial sector, excessive household debt and associated high unemployment. We believe that Mr Bernanke knows this. Indeed, in a speech from 2002 that we have quoted before, he cites currency devaluation as an effective means of policy in the event that the domestic money and credit transmission mechanism breaks down:

...there have been times when exchange rate policy has been an effective weapon against deflation. A striking example from U.S. history is Franklin Roosevelt's 40 percent devaluation of the dollar against gold in 1933-34, enforced by a program of gold purchases and domestic money creation. The devaluation and the rapid increase in money supply it permitted ended the U.S. deflation remarkably quickly. Indeed, consumer price inflation in the United States, year on year, went from -10.3 percent in 1932 to -5.1 percent in 1933 to 3.4 percent in 1934.17 The economy grew strongly, and by the way, 1934 was one of the best years of the century for the stock market. If nothing else, the episode illustrates that monetary actions can have powerful effects on the economy, even when the nominal interest rate is at or near zero, as was the case at the time of Roosevelt's devaluation. [emphasis added]4

Now think about this for a minute. Mr Bernanke is on the record advocating currency devaluation as an effective means of ending deflation, supporting the stock market and promoting economic growth when interest rates are near zero. Well, with interest rates near zero and the Fed already buying Treasuries systematically to prevent any shrinkage in the monetary base, an obvious possible conclusion one can draw from the Fed’s recent, explicit statement that inflation is too low amidst weak economic activity, is that the Fed is moving closer toward advocating a policy of dollar devaluation as the means to bring an end to deflationary pressures, support the stock market, promote economic growth and contribute to a decline in unemployment.

We say “advocating” for a reason, in that it is the US Treasury, not the Fed, which has the mandate for US currency policy. Any decision to deliberately devalue the dollar must therefore be made by the Treasury, presumably on the executive order of the president, although it is possible that an act of Congress would be used to provide additional legitimacy for such action.5 The Fed, however, would act as the agent, selling dollars in exchange for foreign currency government bonds, most probably those of the euro-area and Japan–the largest foreign markets–but possibly also others.

In the event that the euro-area and Japan are willing to allow their currencies to appreciate, then the cost of goods imported from those countries into the US is going to rise. The same is true for imports from any country which is willing to allow its currency to rise versus the dollar in this fashion. In time, the US will find that import price inflation is pushing up the prices of consumer goods generally. As US wages are likely to remain stagnant amidst high unemployment, however, it is only when the dollar has fallen far enough to make US workers’ wages somewhat cheaper relative to the rest of the world (ROW) that businesses will begin to hire US workers again and unemployment will begin to decline.

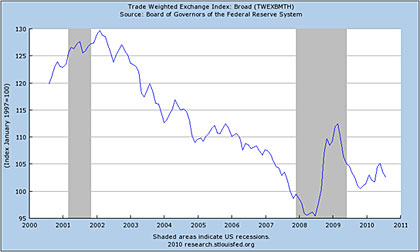

How large a decline in the dollar is required to allow for a meaningful adjustment in relative wages? While it is impossible to make precise estimates, taking a look at real effective exchange rates, which allow for such cross-border wage comparisons, something on the order of 30-40% is probably required. This is in addition to the approximately 20% devaluation of the dollar that has already taken place since 2002, when the current downtrend began.6

In broad trade-weighted terms the dollar has only declined by 20% since 2002

Once unemployment declines far enough, say to 5% or so, wage pressures are likely to build. Eventually, wages will rise to the point that they enable households to service previously accumulated debt burdens. Once that happens, sustainable growth will again be possible, although households will find that their global purchasing power and relative standard of living has declined dramatically. This is another lesson of the stagflationary 1970s, in which the US standard of living was more or less stagnant yet that of the ROW, including Japan and Germany, increased markedly.

Those who recall the 1970s must wonder why on earth the Fed would want to enact policies which would in all probability lead to a similar set of stagflationary conditions. Well, the Fed might claim that it doesn’t have much of a choice. Once originated, debt needs to be serviced. It can however be serviced in a strong or in a weak currency. A country with a solid infrastructure and industrial base and with plentiful natural resources might manage to service debt in a strong currency just fine. Indeed, had the US run up its accumulated debt in order to finance sensible investment projects over the years, it would most probably be able to manage to service this debt without resorting to dollar devaluation. But sadly, much of the debt the US has piled on in recent decades has been used to finance consumption rather than investment. And to the extent that the US has invested in rather than consumed capital, much of it went into malinvestments: the dot.com and subsequently far more massive housing and securitised credit bubble, which grew with the support of all manner of federal subsidies–courtesy of Fannie and Freddie, among other federal agencies–and, of course, artificially low Fed interest rates.

The debt-financed consumption and housing boom is now over. Yet the debt remains. It can not be properly serviced with the existing productive resources of the economy. As such, the debt needs to be either devalued or defaulted on. The Fed and US policymakers generally have made it exceedingly clear that they prefer to devalue–inflate–the debt burden away rather than to go through a comprehensive default and debt restructuring process.

Of course that other road could be taken. But why are policymakers so dead set against it? Well believe it or not, Chairman Bernanke himself has previously weighed in on this matter. In his opinion, it comes down to politics and the ability, or inability, to make tough choices:

[R]estoring banks and corporations to solvency and implementing significant structural change are necessary for ... long-run economic health. But in the short run, comprehensive economic reform will likely impose large costs on many, for example, in the form of unemployment or bankruptcy. As a natural result, politicians, economists, businesspeople, and the general public ... have sharply disagreed about competing proposals for reform. In the resulting political deadlock, strong policy actions are discouraged, and cooperation among policymakers is difficult to achieve. [emphasis added]7

Now wait a minute. When did Bernanke say that he preferred “comprehensive economic reform” rather than zero interest rates and open-ended liquidity creation (eg quantitative easing)? Well guess what, he was not talking about the US in the above paragraph, but rather about Japan. What Mr Bernanke thinks is required for Japan to achieve “long-run economic health” somehow doesn’t apply to the United States!

But of course it does. The above quote indicates that he probably knows that it does. But as he also says above, to take such action “will likely impose large costs on many”. Indeed it would, including of course those financial institutions supposedly regulated by the Fed, many of which have been bailed out, yet are still sitting on large holdings of bad loans and toxic securitised debt. It is much easier to understand recent Fed policy actions in light of the above admission that the Fed is focused primarily, perhaps exclusively, on the short-run health of the financial system rather than long-run health of the US economy generally.

***

It is quite possible that the euro-area governments, Japan and other countries will resist a US Fed policy of foreign asset purchases by countering with purchases of their own, the net result being that the dollar does not devalue but rather that the global money supply soars. There is no doubt that, in this situation, investors will attempt to escape the risk of a general, global fiat currency devaluation by fleeing into real assets, most probably liquid commodities, including of course precious metals. An all-out currency war could thus spark an incipient hyperinflation which, if policymakers did not take immediate action to restore fiat currency credibility–possibly by implementing Volcker-style rigid money supply targets, or even by pegging to gold–could spiral out of control. While we consider a global hyperinflation scare unlikely, the fact that a global currency war has begun should give investors pause for thought.

The Amphora Liquid Value Index (through 28 September 2010)

Source: Bloomberg LP

THE AMPHORA LIQUID VALUE INDEX represents the return on a dynamically-rebalanced portfolio of broadly and efficiently diversified commodities and currencies, intended to retain its real value in a wide variety of circumstances, including both inflation and deflation.

© Amphora Capital LLP. All rights reserved. Amphora Capital is registered in England and Wales under the number OC345497.

Resources

1 Foreign exchange intervention has a history as long as that of supposedly free-floating currencies. Following the unilateral US abandonment of the gold standard in 1971, there was active management of most exchange rates for several years, with Japan in particular resisting currency strength through frequent intervention. In the 1980s, there was a coordinated effort to weaken the dollar in 1985 and, from 1987, to support it. In 1992, the Bank of England tried in vain to support sterling in one of the most spectacular failed interventions of all time. In 2000, the ECB intervened to support the euro on multiple occasions. Over the past two decades, Japan has intervened numerous times to weaken the yen.

2 Last week Brazilian Finance Minister Mantegna declared that a global currency war was underway and said that Brazil would do everything required to protect its economy.

3 For the complete statement please visit the Fed’s website at www.federalreserve.gov

4 While already acknowledged at the time as a particularly important speech by Bernanke, who had only recently begun his first term as a Fed governor, in retrospect it can be considered one of the most important Fed speeches in history, in that it lays out the roadmap that the Fed has followed ever since the credit crisis began in 2008. Click here for the link to the speech

5 The US policy of dollar devaluation in 1933-34 began with a series of executive orders and culminated in the Gold Reserve Act of 1934. For those curious, the initial legal basis for these actions was the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917, which although enacted as an emergency measure during WWI, had not been subsequently rescinded. Among other things, it permitted the president to “...investigate, regulate, or prohibit, under such rules and regulations as he may prescribe, by means of licenses or otherwise, any transactions in foreign exchange, export or earmarkings of gold or silver com or bullion or currency, transfers of credit in any form (other than credits relating solely to transactions to be executed wholly within the United States), and transfers of evidences of indebtedness or of the ownership of property between the United States and any foreign country, whether enemy, ally of enemy or otherwise, or between residents of one or more foreign countries, by any person within the United States.”

6 These measures of dollar strength and relative wage costs are based on broad indices which include developing as well as developed countries. While the dollar has fallen approximately 40% since 2002 versus the euro and yen, it has fallen by far less relative to emerging market currencies, including the Chinese yuan. These developing economies, of course, have become far more important US trading partners over the past decade.

7 Believe it or not this excerpt is from the same 2002 speech quoted previously.

DISCLAIMER: The information, tools and material presented herein are provided for informational purposes only and are not to be used or considered as an offer or a solicitation to sell or an offer or solicitation to buy or subscribe for securities, investment products or other financial instruments. All express or implied warranties or representations are excluded to the fullest extent permissible by law. Nothing in this report shall be deemed to constitute financial or other professional advice in any way, and under no circumstances shall we be liable for any direct or indirect losses, costs or expenses nor for any loss of profit that results from the content of this report or any material in it or website links or references embedded within it. This report is produced by us in the United Kingdom and we make no representation that any material contained in this report is appropriate for any other jurisdiction. These terms are governed by the laws of England and Wales and you agree that the English courts shall have exclusive jurisdiction in any dispute.