By the late-1990s it became clear to informed observers that the substantial portion of EU countries that had signed the Maastricht Treaty in 1992 were going to proceed with a European monetary union (EMU) as codified in the Treaty, most probably on schedule, in 1999. Previously dismissed as a Franco-German political pipe-dream, there was a growing air of excitement in financial markets as the political winds blew ever stronger in the direction of making EMU a reality. But on the trading floors of banks and in the boardrooms of asset management firms, such excitement quickly gave way to the practical reality of how best to prepare for the euro. What were the implications for the EU economies? Their financial markets? How would the euro trade as a currency? How would the various euro sovereign bond markets trade vis-à-vis each other? Or national equity markets? Most importantly, how should investors adjust their existing forecasting, valuation and asset-allocation methods for a single European currency?

At the time, I was working as an investment strategist at a major German bank in Germany and it was in this context that my colleagues and I set about developing EMU-specified financial market analysis tools. The first, most obvious problem that had to be dealt with was, if you create a single currency out of several, what happens to the intra-EMU FX risk? After all, in 1992 and 1995 there were major EU currency crises. These had made (or lost) bond and currency traders a fortune.

But wait. Doesn’t the FX risk just disappear, as if European policymakers had waved a magic wand? Well, no. Just as there is no free lunch in economics generally, there is no magic wand in economic policy. Policymakers who claim otherwise are like magicians distracting their audience. As is the case in the physical world, in which there is conservation of energy–the first law of thermodynamics–there is also conservation of economic risk. It cannot be eliminated by waving a magic wand. It can, however, be transformed from one type of risk to another.

With respect to EMU, if the FX risk does not simply disappear, where does it go? Consider what creates FX risk in the first place: Currencies fluctuate for a variety of reasons which ultimately boil down to relative rates of sustainable economic growth and expectations thereof. As the EU economies have fluctuating relative growth rates, this creates fundamental FX risk. Only by eliminating these fluctuations could the real, underlying relative economic risk also be eliminated. But if these fluctuations are not eliminated, the risk remains. Once again we ask: Where does it go?

There answer, as it turns out, is credit risk. When a country’s relative sustainable growth rate (or expectations thereof) declines and the currency devalues it improves the terms of trade and, as such, raises the expected future growth rate. This in turn increases inflation and tax revenue expectations which make it easier, in principle, to service debt denominated in the domestic currency. As such, other factors equal, as a currency devalues, domestic credit risk declines in tandem.

But consider now what happens in EMU. A country that underperforms cannot devalue. There is no improvement in the terms of trade and hence no increase in either inflation or tax revenue expectations. Indeed, these are more likely to decline. Debt service thus becomes more rather than less onerous. Credit markets thus demand a higher risk premium to hold the debt. Unless steps are taken to improve relative economic competitiveness, this higher risk premium may remain in place indefinitely, draining resources from the economy and reducing the future growth rate. Ultimately, the only ways to break out of a vicious circle of economic underperformance and higher relative borrowing costs is either to secede from EMU and devalue or to restructure the debt. In either case the fundamental risks are ultimately realised.

This is what is happening in Greece and Ireland today. It might soon take place in other EMU member countries. Those investors who have understood that EMU did not eliminate but rather transformed economic risk and who observed the chronic relative economic underperformance of Greece and certain other euro members were well-positioned to profit from onset of the euro sovereign debt crisis.

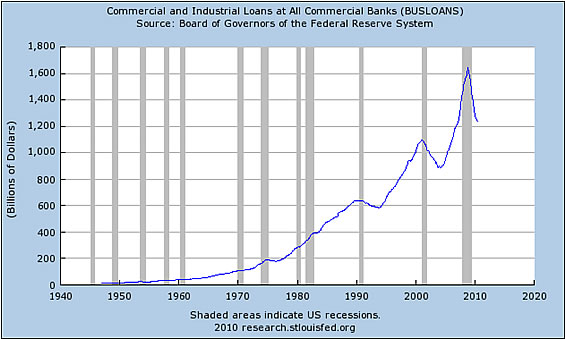

Our discussion of the conservation of risk does not end there. As the US Fed now considers new measures to stimulate bank lending, business investment and employment, they claim to be brandishing a powerful policy wand. But can they really reduce or eliminate economic risk, or merely shift it by sleight of policy hand from where it is clear for all to see to where it is rather disguised by the smoke and mirrors of an increasingly opaque Federal Reserve balance sheet? And as they shift risk around, are there negative, unintended consequences for the economy and financial markets?

HAS THE FED BECOME PATHOLOGICAL?

Fed Chairman Bernanke’s keynote speech at the Kansas City Fed’s annual Jackson Hole Symposium is notable for its somewhat detailed discussion of additional policy options being considered by the Fed now that the recovery is faltering. Yet this did not come as a complete surprise. Much of the content was telegraphed in a recent op-ed by Bernanke’s friend and long-time colleague, Alan Blinder of Princeton, a former Fed vice-chairman.1 In this piece, Mr Blinder lays out the framework for how the Fed should go about responding to the clearly intensifying double-dip in the economy. In our opinion, it is highly likely that Mr Blinder is speaking for Mr Bernanke who, in his official position as Fed Chairman, is not able to clearly advocate any course of action which has not been agreed by his FOMC colleagues. Indeed, recent reports indicate that a number of Fed officials are currently uneasy with the existing set of unconventional policies in place and would resist additional actions. So what, exactly, did Mr Blinder have to say, and how are financial markets likely to respond if and when the Fed eventually acts as he suggests? He makes several specific policy recommendations that we shall consider in turn.

Mr Blinder first considers expanding existing polices. For example, having already purchased a huge amount of mortgage-backed securities (MBS), in particular Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac paper, the Fed could buy even more, thereby growing the monetary base even further and, at the margin, reducing mortgage borrowing costs. However, he then points out that such costs are already extremely low in a historical comparison and the Fed might not get much bang for it’s printed buck by going down this path. He draws the same conclusion with respect to the Fed’s rhetoric of commitment to a prolonged period of unusually low interest rates. Financial markets have already pushed down long-term interest rates to extremely low levels and more rhetoric to this effect would be unlikely to accomplish much, if anything.

Having largely dismissed the desirability of these two options, he then produces three more with his clear support. First, the Fed could begin to buy private sector assets in an effort to reduce borrowing costs for businesses. If banks are still unwilling to lend, so the thinking goes, then the Fed should lend to businesses directly rather than through the banks. While this sounds nice on paper, it would be hugely complicated and political in practice. Which firms should be selected? Why? How much should the Fed buy? In which maturity? The degree of economic micro-managing implied by such a policy and the obvious potential for political favours and other abuse is massive. Yet we would not presume to dismiss completely the possibility that a desperate Fed might take such desperate measures.

Second, and somewhat neater from an operational point of view would be for the Fed to lower the rate of interest it pays on so-called "excess" reserves, which are cash reserves banks hold in excess of what they need to hold against outstanding loans. Under normal circumstances, banks don’t hold any excess reserves as this prevents them earning any incremental interest in the interbank lending market. However, when interest rates are close to zero and there is little if any demand for new borrowing by businesses and households trying to de-leverage their balance sheets, banks have little incentive to mobilise their excess reserves. As such, they remain at the Fed, earning a paltry but risk-free 0.25%.

But what if the Fed were to lower this rate to zero? Would that be enough to stimulate lending? Mr Blinder isn’t so sure, so he goes one step further. What if the Fed were to pay banks a negative interest rate for holding these reserves, in effect charging them a fee for not lending out these funds? Mr Blinder believes that banks would quickly begin lending in order to avoid such a fee.

Mr Blinder’s final suggestion is that the Fed ease bank examination requirements to encourage relatively healthy banks to take greater risks extending credit to riskier borrowers. For him to make such a recommendation, given that just about everyone agrees that aggressive lending practices were one of the key ingredients for the US housing bubble, bust and associated global financial crisis and subsequent US recession, is breathtaking to say the least. But we’re quite certain that when Mr Blinder makes this suggestion, he does so with complete seriousness and certainty that he represents the US economic policy mainstream. This, of course, should tell us something about that “mainstream”. Just who are these economists anyway? Did they predict the crisis? Did they predict the double-dip? If not, why not? And why on earth do they do persistently prescribe the same monetary “medicine” that has already nearly killed the US economy? Isn’t doing the same thing over and over again, anticipating a different response, a classic definition of insanity?

The private sector is de-leveraging at a historic pace...

...but the public sector is taking up the slack

Yes, the US economic mainstream appears insane. There, we said it. Mr Blinder could not have been implicitly clearer on this point. In this and other op-eds and other academic and policy papers, we read the same neo-Keynesian rubbish over and over, that the solution to excessive debt and consumption is even more debt and excessive consumption. And if the private sector is not willing to co-operate in such insanity–and quite clearly it is not–then the Fed and the government must step in to provide it. It’s for our own good. It’s as if a government-run rehab clinic were prescribing progressively larger rather than lower doses of a drug in a chimerical effort to help an addict. It can’t possibly work. With each larger dose, the patient will remain addicted as before while the side effects, anticipated or not, grow and grow.

***

Let’s examine the likely side effects of Mr Blinder’s ideas. One glaring omission in his op-ed is that there is absolutely no mention of how Fed policy actions, past or present, have any impact on economic activity globally. It is as if the US economy existed in a vacuum. Of course it does not, although many prominent mainstream US economists could be forgiven some ignorance on this matter as they have spent little if any time working and living abroad. As the global reserve currency, changes in US interest rates, money supply, bank lending, business investment and economic conditions generally have a massive impact on the rest of the world (ROW), for better or worse. With US interest rates so low and with many currencies either officially or unofficially pegged or “managed”–preventing large moves via periodic intervention vis-à-vis the dollar, there is a clear transmission mechanism, via global capital and trade flows, between expansionary, inflationary Fed policy and global economic conditions. Domestic US CPI may be close to zero as a result of the massive private-sector de-leveraging currently underway, which prevents the so-called “money-multiplier” from operating normally. But from the perspective of a growing number of countries, Fed policy is increasingly malevolent, complicating attempts to achieve sustainable, stable growth. In a growing number of cases, aggressively expansionary Fed policy is leading to a dramatic surge in consumer price inflation.

India and China, both now major economies, provide important examples. In India, CPI is currently running at 14.4% y/y, up from under 5% in mid-2008. In China, CPI is much lower at 3.3% y/y, although it has surged over the past year from nearly -2% y/y. At this rate of climb, China’s CPI y/y will be in the double digits by late 2011.

With the US economy weakening sharply again, the Fed has already determined that it should not allow its balance sheet to shrink as mortgage-backed securities mature. As discussed above, the Fed is now considering more aggressive measures to prevent further weakness. Yet the last thing such countries desire is for Fed policy to stimulate their overheating economies even more, to which the Fed might respond: “So what? If you don’t want more stimulus, why don’t you allow your currencies to rise, rather than leaving them pegged or “managed” vs the dollar?” Fair enough. Fixed or “managed” exchange rates clearly strengthen the transmission mechanism between US monetary conditions and global economic activity. By allowing their currencies to strengthen rather than remain pegged or “managed”, foreign countries would find that much unwanted stimulus was stopped at the border.

It could be that surging global CPI is a side-effect the Fed in fact wants. All countries have a CPI pain threshold. The Fed and US policymakers generally know this, although they don’t know precisely where it is. Only by adding progressively more monetary stimulus can the Fed eventually dislodge the fixed and “managed” exchange rates which are diverting Fed stimulus from the domestic to the international economy. In the face of stronger currencies globally, the US would almost certainly begin to import a substantial amount of price inflation, via both commodities and manufactured goods, in effect devaluing US debt and, of course, consumers’ purchasing power in the process.

Chairman Bernanke, in an important speech from late 2002, when the Fed was concerned about the risks of deflation, argued that the Fed could always prevent deflation if necessary with currency weakness. He specifically cited how a large (60%) devaluation of the dollar in 1934 helped to ease the deflationary price pressures of the Great Depression.2 Perhaps history is going to repeat.

***

Let’s now focus on what we regard as Mr Blinder’s most provocative suggestion for how to provide effective additional monetary stimulus, namely, negative interest rates on excess reserves. Imagine a bank that is holding substantial excess reserves at the Fed given a lack of attractive lending opportunities. Currently those reserves are earning only 0.25%, but at least that is risk-free. But what if this bank suddenly learns that these reserves will now pay a negative 1%?

Naturally, the bank will seek to avoid paying this 1% fee without taking incremental credit risk. After all, it is not as if this 1% fee makes potential borrowers more creditworthy. In practice, there is only one way to lend money without taking incremental credit risk: Lend it to the US government through purchases of Treasury securities. So as a first step, should the Fed impose a 1% fee on excess reserves, banks are likely to move a substantial portion of these reserves into the Treasury market. Given that excess reserves are currently about tn, this implies a large rise in Treasury prices and thus large decline in yields.

While no doubt convenient for the government, already running a huge deficit which is destined to grow exponentially as the economy weakens, should we assume that lower government borrowing costs will be passed on to the private sector? And to the extent that they are, is the private sector going to decide to leverage up again? And even if they do, are banks going to want to lend to these risky borrowers? With the monetary transmission mechanism as damaged as it already is by excessive debt and leverage, it is far from clear that the Fed would get much bang for its printed buck even if Treasury yields plummeted to near zero, as indeed Japanese government bonds did many years ago. It wasn’t much if any help for Japan and we doubt it will provide much if any help for the beleaguered US private sector. But while negative interest rates are unlikely to provide much if any support for the economy, they might in fact do serious damage via unintended consequences. What Mr Blinder fails to consider is how depositors would be affected by his negative rate scheme.

In response to a 1% fee on excess reserves, banks are unlikely to just purchase Treasury securities. They are also likely to reduce interest rates paid on deposits. But with demand deposit rates already slightly negative after fees and with savings account rates necessarily plummeting along with Treasury yields–as banks seek to maintain positive margins–depositors are going to be increasingly reluctant to hold large cash deposits. Why bother paying banking fees when you can just use cash? Why not keep cash in a safe at home for free rather than in the bank for a fee? It is highly probable that, the longer negative interest rates on excess reserves remain in place, the more depositors begin to withdraw funds from the banking system to avoid incurring fees.3

This is where it gets interesting. As banks begin to lose deposits, they also lose their capital base. As capital erodes, banks must either reduce lending or passively accept higher leverage. In either case, the monetary transmission mechanism will break down by even more. In an extreme scenario in which households move en masse into physical cash, there will be a general run on the banking system, something the Fed would no doubt want to avoid. But what could the Fed do in response, other than return the interest rate on excess reserves to positive? Would the Fed seek to prohibit the hoarding of physical cash? Require electronic payment for everyday transactions?

We highly doubt it. Much more likely is that the Fed would back down and allow interest rates to adjust higher, notwithstanding the short-term pain it might cause for the economy. But just for fun, what if the Fed did indeed prevent the use of physical cash for savings and everyday transactions? If hoarding physical cash was made illegal, what would households hoard instead? Gold? Silver? Scotch? Cigarettes? Ammunition? A private sector that wants to save and de-leverage will find a way to save and de-leverage regardless of whatever shenanigans the Fed decides to pull.

***

It should be clear to anyone with basic common sense that Mr Blinder’s aggressive policy prescriptions are highly unlikely to help the US economy to recover and, in fact, are likely to do serious economic damage if implemented. Indeed, we are horrified that such policies are even whispered, much less seriously debated, by past and present Fed officials. Chairman Bernanke’s Jackson Hole speech and Mr Blinder’s expressed views suggest to us that, it is quixotic quest to use future monetary stimulus to fix the problems caused by past monetary stimulus, the Fed risks becoming pathological.

Investors who share our concerns that the Fed is likely to cause more problems than it solves through the application of additional, radical monetary stimulus, need to maintain a defensive investment posture. Diversification is key, but with financial markets in general rising and falling based on increasingly binary and arbitrary Fed policy decisions, there is only limited diversification to be had in US financial assets. And with many other major economies suffering problems of their own, global diversification is also limited. We continue to recommend that investors use alternative assets, in particular defensive, liquid, relatively non-cyclical commodities, to achieve sufficient diversification. While such assets may not offer any yield, neither does cash. And unlike dollars and other currencies, central banks can’t arbitrarily print, dilute and devalue investors’ holdings of oil, gold, wheat, cotton, pork bellies or FCOJ.4

The Amphora Liquid Value Index (through 31 August 2010)

Source: Bloomberg LP

___________________

1 https://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703846604575448022122679194.html

2 The 60% devaluation of the dollar put an end to the US consumer price deflation that had been taking place since 1930. However, while this large devaluation reduced consumers’ purchasing power, it did little to stimulate business investment or reduce unemployment, which remained stubbornly high throughout the 1930s. Although Mr Bernanke claims to have learned much from the Great Depression, including how to prevent consumer price deflation, he doesn’t seem to have noticed that Fed polices did not stimulate investment or reduce unemployment, his consistent rhetoric to the contrary notwithstanding.

3 The Fed might be optimistic that, rather than increase physical cash holdings in lieu of increasingly unattractive bank deposits, households might choose to purchase corporate securities instead. But is it realistic to believe that highly indebted households, facing historic economic and job market uncertainty, are going to substantially increase their financial risk-taking? No, it’s not.

4 In the 1980s film Trading Places, a major commodities brokerage house is taken down by a huge wrong-way bet on the price of frozen, concentrated orange juice (FCOJ). Yet while the brokerage became insolvent, none of those on the other side of the FCOJ bet lost money, as they were taking the risk of the FCOJ price, not the credit risk of the broker. This absence of credit risk in the commodities markets is an important and hugely overlooked source of diversification in a world of excessive debt and leverage.

DISCLAIMER: The information, tools and material presented herein are provided for informational purposes only and are not to be used or considered as an offer or a solicitation to sell or an offer or solicitation to buy or subscribe for securities, investment products or other financial instruments. All express or implied warranties or representations are excluded to the fullest extent permissible by law. Nothing in this report shall be deemed to constitute financial or other professional advice in any way, and under no circumstances shall we be liable for any direct or indirect losses, costs or expenses nor for any loss of profit that results from the content of this report or any material in it or website links or references embedded within it. This report is produced by us in the United Kingdom and we make no representation that any material contained in this report is appropriate for any other jurisdiction. These terms are governed by the laws of England and Wales and you agree that the English courts shall have exclusive jurisdiction in any dispute.