My friend Neil Howe, author of Generations, The Fourth Turning, and other books and president of Saeculum Research, joins us today in Outside the Box with a succinct, eye-opening essay on generational differences in debt levels and attitudes towards debt.

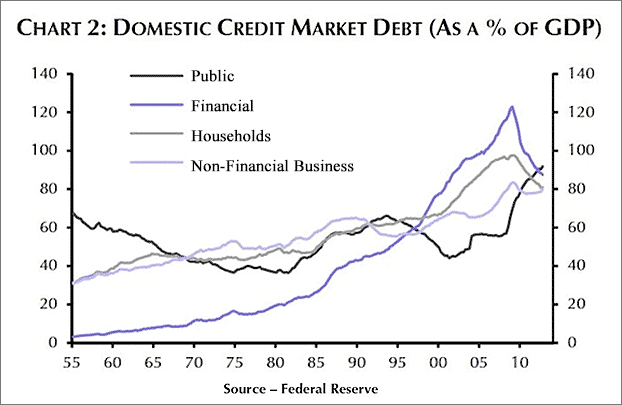

I often write about the problems that come with overindebtedness, but we’re usually talking about public debt, here in the US or abroad. But personal or household debt in America is nearly as massive as government debt, as this chart shows:

As you can see, household debt was relatively stable from the mid-’50s until the turn of the century, when it ballooned for a few years until the Great Recession hit and then was subject to significant deleveraging in the years since. Still, as Neil notes, average household debt is nearly twice as high today as it was in 1989, with most of the increase coming in the form of mortgage debt, although student loans are taking a bite, too – they’re up sixfold, from 8 per household in 1989 to a painful 91 in 2013.

Since these dramatic changes in indebtedness have occurred mostly in the past 20 years – in the span of a generation, that is – they have resulted in very different attitudes toward debt among US generations. The Silent generation (75+) was well-established before the changes hit, is the least burdened by debt – and sees debt in the most positive light, as an opportunity for financial advancement. But the debt they took on, back in the “good old days,” was mostly in the relatively innocuous forms of house and car loans. They weren’t subject to the wave of high-interest credit cards and “seductive Web-based come-ons for low-doc, no-down-payment bubble loans they couldn’t possibly afford,” as Neil puts it, that have plagued Boomers and Gen-Xers scrambling to keep up with the lifestyles of their elders. Millennials (today’s 20-somethings, roughly speaking), who have seen how the generation just ahead of them has suffered, are not surprisingly the most risk-averse when it comes to taking on debt.

There’s more to chew on here, and a lot more to learn about the impact of demographics on economic and social change in America and the world at Neil’s Saeculum Research website.

Your sympathizing with the Millennials analyst,

John Mauldin, Editor

Outside the Box, subscribers @ mauldineconomics.com

Another Day Younger and Deeper in Debt

Americans of all ages are in more debt than they were three decades ago, but what does that say about the health of their balance sheets?

By Neil Howe, President, Saeculum Research

August 19, 2015

A new report from Pew Charitable Trusts that examines debt within each generation finds that as you move down the age ladder, consumers are less likely to view debt in positive terms. This report helps us understand the fascinating changes in behavior and attitude toward debt that each generation has brought into the age brackets they’ve occupied. The Silent, who have accrued so much wealth that their debt is but a blip on the radar, believe debt to be opportunity-enhancing. Boomers are more conflicted, as they’re just beginning to realize that their lavish spending is catching up with them. Younger generations are the least bright-eyed: Generation Xers played it risky at exactly the wrong time and now stand in a mountain of debt, while Millennials who watch their elders struggle to escape the creditor want to avoid debt at all costs.

Average household debt, though below pre-Great Recession levels, is much higher than it was three decades ago no matter how you measure it. According to the Federal Reserve's Survey of Consumer Finances, after adjusting for inflation, the amount of debt held by the average family nearly doubled from ,356 in 1989 to ,114 in 2013. Additionally, household debt as a share of GDP has increased by roughly 20 percentage points over that same time period, from around 60 percent in 1989 to just above 80 percent in 2013. When broken down by type of debt, some interesting trends emerge.

Household mortgage debt, averaged over all households, grew the most in terms of dollar amount, increasing from ,041 in 1989 to ,865 in 2013. And though not as impactful in dollars, student loans have been the most rapidly-growing type of debt, surging more than sixfold from 8 in 1989 to ,791 in 2013.

[Hear: Neil Howe on the Fourth Turning, Cycles of History, and the Future of America (Part 1)]

How indebted is each of today’s generations? Fed data indicate that the Silent are the least burdened. The average 75+ household had just ,805 in total debt in 2013, the lowest of any age bracket. The next best-off are Millennials. The average under-35 house-f course, this amount is hardly small: This generation has overseen the explosion in student loan debt—holding, on average, 25 percent more in these loans than any other age group. As a result, many Millennials are putting off big-ticket purchases like cars or houses.

But the picture looks far worse for middle-aged adults. Among adults ages 65 to 74—a mostly first-wave Boomer age bracket—average household debt is ,718. Last-wave Boomers ages 55 to 64 have an average household debt of 3,805. Xers are the worst off, with a first-wave average debt of 3,862 (mortgage debt of ,863)—and a last- wave average debt of 9,235 (mortgage debt of ,909).

It’s not surprising that indebtedness varies so widely by generation; after all, each is in a different phase of life that comes with varying financial obligations. A more illuminating way to evaluate change over time is to compare each age bracket today with the same age bracket 25 years ago. According to Fed data, the Silent Generation shows the biggest improvement compared to people their age back in 1989. Though the average 70- to 79-year-old household in 2013 had over ,000 in debt (compared to just ,000 in 1989), a Silent household also had 0,000 more in assets than a like-aged household in 1989. Among first-wave Boomers, debt has risen much faster: Thanks to home-equity borrowing, today’s 60- to 69-year-old Boomer household has ,000 more debt than a like-aged household in 1989. But since these Boomers also possess 0,000 more in assets, there is no real cause for alarm.

Among younger cohorts today under age 60, however, we begin to see an increase in debt without a significant increase in assets. For example, 40- to 49-year-olds in 2013 not only had more debt than a like-aged individual in 1989, but also had a full ,000 fewer assets—making this mid-Xer bracket the only one to have fewer assets than the same age group 25 years prior. In 2013, a head of household younger than 35 picked up roughly ,000 more debt—but only accrued ,410 more in assets.

This changing pattern of debt behavior is linked to—and explains—how different generations perceive debt. Unsurprisingly, the Silent see the least downside to debt: According to Pew’s report, 77 percent of Silent believe that loans and credit cards have expanded their opportunities and are worth the inherent risk. When the Silent were in their prime earning years, there was virtually no way to go into debt other than falling behind on mortgage or car payments. Moreover, few of the Silent have experienced overindebtedness, and, even when they did, their upward economic mobility relative to other generations bailed them out (see SI: “Once Again, Economy Hammers Gen Xers and Favors the Silent”).

[Hear Also: Neil Howe on the Fourth Turning, Cycles of History, and the Future of America (Part 2)]

Boomers, though less likely than the Silent to see debt positively, do recognize its advantages at a higher rate—70 percent—than younger generations. Boomers likely recognize that without loans and credit cards, they could never have financed the McMansions, BMWs, or pricey home renovations that underlie their chosen lifestyles. But an unprecedented share of the generation that pioneered the home equity loan will be paying off their mortgages until the day they die. Mortgage-burning parties, once a common ritual for G.I.s and Silent, have become a relic of the past.

Xers view banks as an effortless and all-too-tempting way to convert future income into current consumption. It’s a view that led vast numbers of over-leveraged 30- and 40-somethings to financial ruin after the Great Recession. This generation took on heavy debt in a risky attempt to “keep up” with the lavish standard of living that their Boomer predecessors ushered in—a living example of James Duesenberry’s relative income hypothesis. For Xers, banks were never the trusty Roman-columned institutions that tried to help them buy better lives, but instead seductive Web-based come-ons for low-doc, no-down-payment bubble loans they couldn’t possibly afford. In fact, many Xers are moving away from banks entirely and toward alternative financial institutions that can help them with one-and-done transactions whenever they need it (see II: “More Americans Are Giving Up on Banks”).

Millennials, according to Pew’s study, are the least likely to see loans and credit cards as opportunity-enhancing. Risk-averse Millennials saw what happened to their elders’ balance sheets during the recession and many tend to believe that the less one has to deal with a bank, the better. For Millennials, a credit card seems like a risky proposition compared to a prepaid debit card. Additionally, many Millennials simply have not yet accrued enough wealth to necessitate banking. It’s too early to tell, however, how Millennials will collect debt relative to older generations. Whether this generation will spend heavily in order to keep up with their parents’ standard—or whether they will take their risk aversion into middle age—remains to be seen.

Trend Implications

Indebtedness has grown across all age groups over the past 25 years, with different generations’ experiences coloring how they see it. The Silent, who hold the least debt and also far more assets that those at the same age did in 1989, are the most likely to view debt as beneficial. Most Boomers, who recognize debt as the engine that allowed them to finance their chosen lifestyles, also see debt positively. However, views are less rosy among Xers, who hold the most debt and whose 40-somethings are the only age bracket to have fewer assets than their counterparts in 1989. And Millennials—saddled with higher levels of student loan debt and wary of banks— agree with Xers.

The generational correlation between debt and assets has shifted over time. Older generations—those showing the most improvement in their balance sheets— also show a clear negative correlation between debt and assets. That is, poorer households tend to have the most debt. The top third of Silent debtors have barely half the net worth of their debt-free peers (5,000 versus 7,000). However, this relationship is flipped with younger generations. The top third of Xer and Millennial debtors have a net worth over five times greater than their debt-free counterparts. Contrary to what one might think, this positive correlation does not lead young people to associate high indebtedness with personal success.

Student loan debt will continue to dominate the headlines. Fed data indicate that, in 2009, student loan debt passed auto lending and credit cards as the greatest nonmortgage source of U.S. household debt. In fact, among Millennial households under age 35, every type of debt except student loans is smaller than it was for Xers at the same age. In response to this crisis, the federal government has rolled out loan forgiveness programs—such as Public Service Loan Forgiveness in the public sector and income-driven plans in the private sector—intended to relieve the burden. Presidential hopeful Hillary Clinton even proposed a 0 billion higher education proposal to reduce student-loan interest rates.

Today’s generations will need different debt-related services as they enter new phases of life. Each generation’s debt profile presages the financial concerns that will become tomorrow’s big opportunities. When Boomers are the age of today’s Silent, their lack of home equity suggests that reverse mortgages will plunge in popularity. And their children will need assistance coping with the heavily indebted homes and assets they inherit. When Xers are the age of today’s Boomers, the phase of life when consumption is typically highest, their spending will likely be constrained by their heavy debt burden. Similarly, Millennials’ exploding student debt suggests that they may ultimately embrace a “new normal” of smaller mortgages and lower spending even decades from now.

Suggested Reading

Jesse Bricker, et al. “Changes in U.S. Family Finances from 2010 to 2013: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances.” Federal Reserve Bulletin 100.4. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. September 2014.

Jonathan Garber and Andy Kiersz. “There’s a big problem with the government’s offer to ‘forgive’ your mountain of student-loan debt.” Business Insider. August 11, 2015.

Susan K. Urahn, et al. The Complex Story of American Debt. Pew Charitable Trusts. July 2015.

The article Outside the Box: Another Day Younger and Deeper in Debt was originally published at mauldineconomics.com.