Part VI is the last of the series of reports from the 10th annual Strategic Investment Conference, presented by Altegis Investments and John Mauldin. Dr. Lacy Hunt, of Hoisington Investment Management, presents his views of the impact on economies when they become heavily leveraged.

You can read the previous presentations by clicking the links below.

Part I: Niall Ferguson – The Great Degeneration

Part II: Jeff Gundlach – Why Own Bonds At All

Part III: A. Gary Shilling – Six Realities In An Age Of Deleveraging

Part IV: Mohamed El-Erian – Putting It All Together

Part V: David Rosenberg – The Potemkin Rally

Here are Dr. Lacy Hunt’s views.

Let's begin by taking a trip back in history. In the 1930's there was a 60% devaluation in the U.S. dollar as the economy struggled with the ongoing depression. Franklin D. Roosevelt felt that the cure for the economic malaise was higher taxes and more spending.

Dr. Irving Fisher, famous for his 1929 prediction that stocks had reached a "permantaely high plateau," argued against increasing taxes but was ultimately no match for FDR.

The resulting surge in taxes ultimately destroyed economic growth, but in the end, the saving grace for FDR was the entry into WWII.

There are important parallels between then and now. In both cases there has been a major cyclical problem combined with a major debt overhang.

In 2013 – taxes paid will rise by 5 billion. As a percentage of GDP that increase in taxes paid represents a tax increase of 1.7%.

Therefore, if we assume that there is no multiplier effect on those dollars, then there is a strong possibility that nominal economic growth will fall to 2% by the end of the year. This doesn't include any impacts from the spending cuts under the "sequester" or the onset of the Affordable Healthcare Act.

The standard forecast for economic growth this year, by both the Federal Reserve and the majority of economists, is that it would be the slowest in the first quarter and then gradually strengthen through the rest of the year. This is absolutely wrong.

Tax increases, and ultimately the taxes paid, have a lag effect on the economy. Overall, individuals are reactive – not proactive. When tax rates are increased individuals do not immediately adjust for the higher taxes that they will have to pay down the road. Rather they continue their behavior until the impact of the higher tax rates is felt by lower levels of discretionary income. It is then individuals begin to adjust behavior.

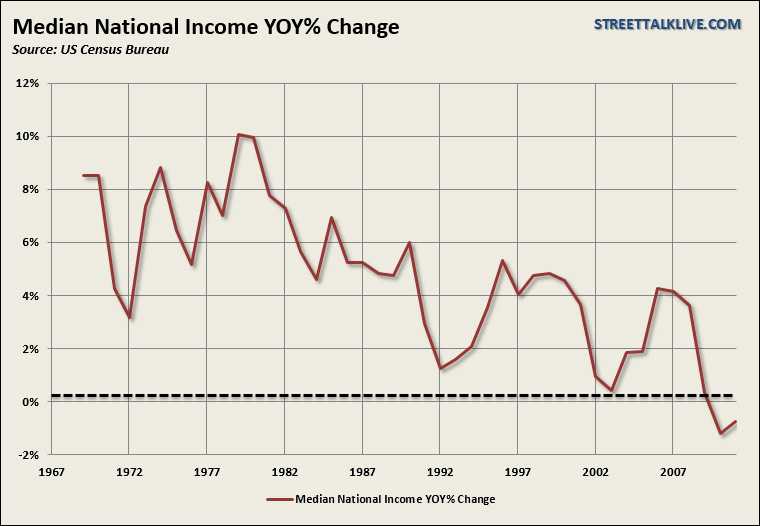

In the current economic situation we have a loss in the standard of living. Wages, overall, have failed to increase at a rate to even offset inflation and, therefore, an increase in taxes in first quarter will show up as a hit to economic growth in later quarters.

In reality, history shows that when there are permanent increases in tax rates the net effect will be a to loss in GDP for every in taxes. This means that an increase of 5 billion in taxes would actually translate to a 0 to an 5 billion dollar drag on economic growth.

Moreover, the effect of higher taxes, and the drag on economic growth, will not be contained within just this year but will trail over the next 2 years.

As I stated earlier, the impact of higher taxes on consumption is likely to be far more impactful than currently estimated as they come at a time when incomes have not increased. Real median household incomes have fallen to the lowest level since 1995. Therefore, higher taxes will continue to erode the standard of living which is already strained.

Take a look at the latest employment report for April, 2013. There was no increase in the weekly earnings in the latest employment report.

Inside the latest employment report was a new measure in the BLS data called the "wage bill". While the number of jobs increased - the wage bill dropped. This was due to a cut in the hours worked combined with wages that are rising at a pace less than the rate of inflation.

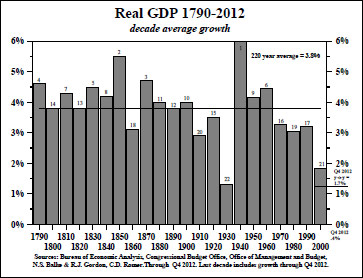

"Our present economic situation is nearly unparalleled in American history. An examination of the real economic growth rate of each decade in the United States from 1790 to 2012 reveals the unprecedented sluggishness of our present economic environment. The 1.8% average rise in the thirteen years of this century is less than half of the 3.8% growth rate since 1790. The only decade that witnessed worse economic conditions was, of course, the 1930s."

The current economic malaise explains much about several things such as:

- Why the birth rate has fallen to the lowest levels since the 1920's.

- Why employment participation is weak.

- Why there are record levels of food stamp participation, etc.

The current low, and sustained, levels of economic growth is the primary reason why we are currently experiencing the weakest level of "opportunity" since the depression.

Reinhart & Rogoff Were Right

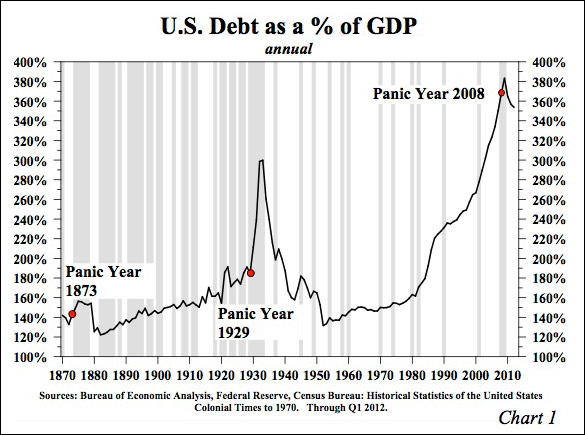

Since 2009 we have increased the Federal debt from Trillion to .5 Trillion. This in an unprecedented increase over any 5 year period in history. This, of course, begs the question: "When is enough – enough?"

What these numbers suggest is that the main economic model employed by the Federal Reserve is flawed. We are using the wrong assumptions.

In their final forecast for 2011 the Fed predicted a 4% economic growth rate by the end of the year. They turned out to be twice as high as the actual outcome. The same occurred for 2012.

The problem is that there is simply no way to reconcile the optimistic language and forecast as produced by the Federal Reserve with the real economy.

The reason that economic growth is not responding to the Fed's monetary policies that because we are currently well above the 260% of total debt to GDP.

Why is this level important?

At current debt levels we are no longer productive. Regardless of your personal view point you have to agree that something is amiss.

- Standard of living has fallen

- GDP growth is weak

- Debt continues to rise.

- Velocity of money is falling.

What Is Debt?

"Debt is future consumption denied."

When you take on debt it must create an income stream that services the debt and repays the principle – when it doesn't; it becomes deleterious to economic growth.

There is now a negative feedback loop of increasing debt levels on economic growth. When is enough, enough?

"I have no political bias. I am an investment manager and my job is to get the story right.

Bad things happen when government debt exceeds 100% of GDP. Four studies published in just the past three years document this conclusion. These studies are highly relevant since OECD figures indicate that gross government debt exceeds 100% in the U.S., Europe, Japan as well as in other OECD member countries. Three of these studies were conducted by foreign scholars and published outside the United States thus avoiding attachment to the unfortunate domestic political debate. Here are the studies, starting with the one with the broadest implications:

(1) In Government Size and Growth: A Survey and Interpretation of the Evidence, Swedish economists Andreas Bergh and Magnus Henrekson find a "significant negative correlation" between size of government and economic growth."

Specifically, "an increase in government size by 10 percentage points is associated with a 0.5% to 1% lower annual growth rate." (Journal of Economic Surveys, April, 2011)

(2) In The Impact of High and Growing Government Debt on Economic Growth, An Empirical Investigation for The Euro Area, Cristina Checherita and Philipp Rother find that a government debt to GDP ratio above the turning point of 90-100% has a "deleterious" impact on long-term growth. Additionally, the impact of debt on growth is non-linear. This means that as the government debt rises to higher and higher levels, the adverse growth consequences accelerate. (European Central Bank, Working Paper 1237, August 2010)

(3) In The Real Effects of Debt, Stephen G. Cecchetti, M.S. Mohanty and Fabrizio Zampolli determine "beyond a certain level, debt is bad for growth. For government debt, the number is about 85% of GDP." (Bank for International Settlements (BIS) in Basel, Switzerland, September, 2011)

(4) In Debt Overhangs: Past and Present - Post 1800 Episodes Characterized by Public Debt to GDP Levels Exceeding 90% for At Least Five Years, Carmen M. Reinhart, Vincent R. Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff confirm that public debt overhang episodes are associated with growth over one percent lower than during other periods, and such episodes lasted an average of 23 years. They write "the long duration also implies that cumulative shortfall in output from debt overhang is potentially massive". (National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 18015, August 2012)

When private debt to GDP rises above 160% to 175% of GDP, growth is also stunted. This argument is also operative since private debt to GDP in the U.S. was 260% of GDP as of the fourth quarter of 2012.

The point on private debt is a serious matter since it strikes at one of the core purposes of central banking – to promote private credit growth. But this is only valid for normal considerations and not when private debt is excessively high. When private debt is excessive, efforts to promote more private debt are counterproductive, thus the Fed is destabilizing rather than facilitating economic growth. The two major studies on private debt, both completed in the past two years and published outside the United States, bear directly on this issue. The first is the 2011 United Nations

Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) study, Too Much Finance, authored by Jean Louis Arcand, Enrico Berkes and Ugo Panizza. They find a negative effect on output growth when credit to private sector reaches 104% to 110% of GDP. The strongest adverse effects are for credit over 160% of GDP. The second is the 2011 BIS study referenced above. It finds that these negative consequences, or what the BIS economic advisor Cecchetti refers to as the point at which debt levels turn "cancerous", start at 175% just slightly more than the UNCTAD study."

The point here is that regardless of the current debate - Reinhart and Rogoff were right. What all of the studies have shown is that Debt to GDP rises above 90-100% it becomes deleterious to economic growth. However, when debt to GDP rises above 100% you begin to get negative returns (Phillip Rother and Christina Checherita study)

There are 4 linkages to between changes in government debt and economic growth.

- Private Saving

- Public Investment

- Factor Productivity

- Sovereign Long term nominal and real interest rates.

It is clear, from all of the available evidence that higher debt levels are leading to weaker economic growth. There have been 26 episodes since the 1800's where government debt exceeded the economy. In 23 of those cases it led to lower economic growth rates. Furthermore, in each of these cases, there has been a negative impact to output when private sector debt rise above 160%.

This is why 260% (100% of Federal Debt To GDP + 160% of private debt to GDP) of total debt is the level at which the economy experiences a negative impact.

The problem longer term is that extreme over-indebtedness has historically led to higher inflation in advanced economies.

It is one thing when one country is over indebted as there have been other countries that have been able to step up and bail them out. It is quite a different story when virtually every advanced economy is over indebted as there is no one left to step in.

Irrationality

Credible academic research indicates that economic growth deteriorates when debt to GDP reaches critical levels - a condition that has now been met in countries that represent 75% of global GDP. When this reality is coupled with the Fed's inability to create money growth or inflation, the result will invariably be slow nominal GDP growth.

The financial and other markets do not seem to reflect this reality of subdued growth. Stock prices are high, or at least back to levels reached more than a decade ago, and bond yields contain a significant inflationary expectations premium. Stock and commodity prices have risen in concert with the announcement of QE1, QE2 and QE3. Theoretically, as well as from a long-term historical perspective, a mechanical link between an expansion of the Fed's balance sheet and these markets is lacking. It is possible to conclude, therefore, that psychology typical of irrational market behavior is at play. This suggests that when expectations shift from inflation to deflation, irrational behavior might adjust risk asset prices significantly. Such signs that a shift is beginning can be viewed in the commodity markets. The CRB Commodity Index peaked about two years ago at 691, but now stands at 551, a 20% decline despite massive Fed balance sheet expansion. The ability of the Fed to arrest a downside irrational move in risk assets may be limited. Non-risk assets, such as long dated U.S. treasuries, should benefit from this shift in perception.

"Ladies and Gentleman, the problems have not been solved, they have merely been contained."

The one common ingredient to all panics historically has been over-indebtedness.

Source: Street Talk Live