The most recent release from the Bureau of Labor Statistics on employment for the month of December was mostly disappointing with far fewer jobs created than originally thought (74,000 vs 200,000). More importantly, and the only thing that really matters is that the labor force participation rate fell to the lowest level since 1978. It was the case of more than 500,000 people leaving the workforce in December which accounted for the drop in the unemployment rate from 7.0% to 6.7%. The chart below shows the history of the labor force participation rate for context.

[Must Read: Rick Santelli: Labor Force Participation Rate Lowest Since 1978]

The difference between today and 1978 is that back then the LFPR was on the rise versus a sharp decline today. However, as I stated previously in "Fed's Economic Projections - Myth vs Reality" this leaves the Federal Reserve in a bit of a predicament.

"The problem that the Fed will eventually face, with respect to their monetary policy decisions, is that effectively the economy could be running at 'full rates' of employment but with a very large pool of individuals excluded from the labor force. Of course, this also explains the continued rise in the number of individuals claiming disability and participating in the nutritional assistance programs. While the Fed could very well achieve its goal of fostering a 'full employment' rate of 6.5%, it certainly does not mean that 93.5% of working age Americans will be gainfully employed. It could well just be a victory in name only"

This is particularly the case when roughly 1 out of 3 people are no longer counted as part of the work force, 1 out of 3 individuals are dependent on some sort of social support program, and over 17% of personal incomes are comprised of government transfers.

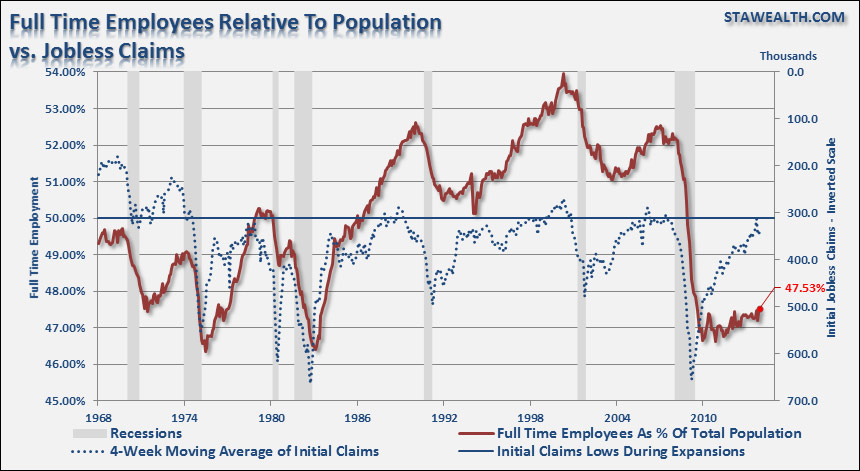

Despite all of the rhetoric, discussions, debates, excuses and finger-pointing in regards to the December jobs report; there is only one chart of employment that truly matters: the number of full-time employees relative to the working age population. Full-time employment is what ultimately drives economic growth, pays wages that will support household formation, and fuels higher levels of government revenue from taxes. If the economy was truly beginning to recover, we should be witnessing an increasing number of full-time employees. Unfortunately, that has not been the case as this measure, as shown by the chart below, is only slightly off the lows witnessed during the financial crisis.

As I stated in "There Is Nothing Weird With Jobs Data:"

"The problem that businesses are beginning to face currently is that while they have slashed labor costs to the bone there is a point to where businesses simply cannot cut further. At this point businesses have to begin to 'hoard' what labor they have, maximize that labor force's productivity (increase output with minimal increases in labor costs) and hire additional labor, primarily temporary, only when demand forces expansion.

The issue of 'labor hoarding' also explains the sharp drop in initial weekly jobless claims. In order to file for unemployment benefits an individual must have been first terminated, by layoff or discharge, from their previous employer. An individual who 'quits' a job can not, in theory, file for unemployment insurance. However, as companies begin to layoff or discharge fewer workers the number of individuals filing for initial claims decline. However, the mistake is assuming that just because initial claims are declining that the economy, and specifically full-time employment, is markedly improving."

The problem is that employment gains are significantly lagging population growth. In December, the population of working age individuals, 16 and older, rose by 178,000 while employment only gained 74,000. The relatively small increase in full-time employment as it relates to the growth of the population shows the existing conundrum. Business owners are very astute allocators of capital and, despite claims of economic recovery, the real underlying economic strength has not warranted hiring in excess of current demand.

The problem is that the pickup in economic activity over the last several months may quickly dissipate as the impact of higher taxes and costs associated with the onset of the Affordable Care Act reduces disposable income of already wage growth deprived workers. This was an issue that I discussed recently in relation to retail sales.

The issue of "labor hoarding" is an important phenomenon that is likely obscuring the real weakness in the underlying economy. Without an increase in the demand part of the equation businesses are likely to continue resorting to further productivity increases to stretch the current labor force farther to protect profitability. However, as we may currently be witnessing, businesses may be reaching the limits of what they can do to continue increasing profits at the bottom line while revenue continues to decline at the top.

The "good news" is that for those that are currently employed — job safety is high. Businesses are indeed hiring, but prefer to hire from the "currently employed" labor pool rather than the unemployed masses. The "bad news" is that, for the unemployed, obtaining full-time employment remains elusive while wages remain suppressed due to the high competition for available work.

This is the "new normal" of an economy that is no longer the manufacturing center of the universe where the real economic prosperity remains elusive as the Federal Reserve's interventions continue to create a wealth effect for market participants which, unfortunately, is only enjoyed by a small minority of the total population. For the other 80% it remains a daily struggle to make ends meet.