As the markets push once again into record territory the question of valuations becomes ever more important. While valuations are a poor timing tool in the short term for investors, in the long run valuation levels have everything to do with future returns. The reason I bring this up is that in 2013 reported earnings per share for the S&P 500 rose by 15.9% to a record of $100.28 per share with roughly 40% of that increase occurring in the 4th quarter alone. That late surge in corporate profits was a bit of a surprise as estimates had been lowered going into the end of last year. The question, however, remains the ongoing sustainability of that growth rate of earnings going forward. John Hussman, via Hussman Funds, made an interesting point in this regard in a recent note:

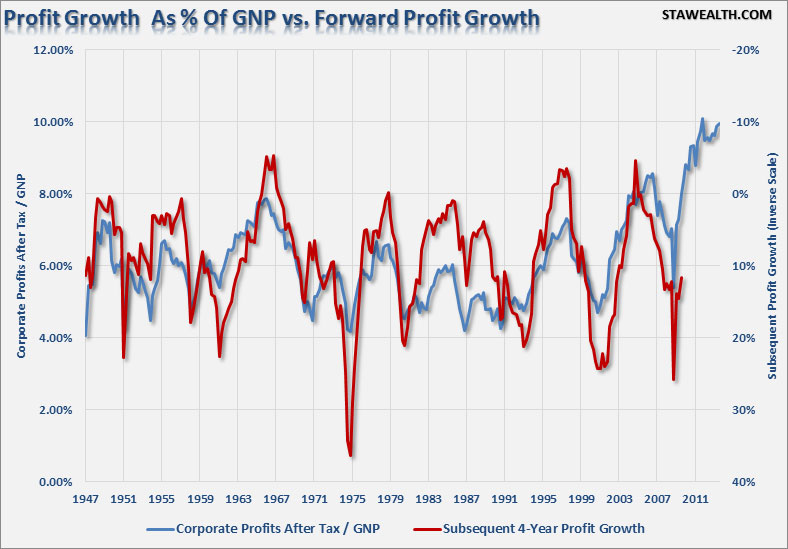

"I’ve noted frequently that after-tax corporate profits as a share of national income are about 70% above historical norms; that these profit shares are heavily mean-reverting and strongly (inversely) associated with subsequent profit growth over the following 3-4 year period; and that the current surplus of corporate profits is the mirror-image of corresponding deficits in household and government savings (a relationship detailed in prior weekly comments). Recent profits data, as well as the entire historical record, are tightly explained by these factors.

Notably, this data is derived from the national income accounts computed by the Bureau of Economic Analysis, and it’s worth understanding how the BEA computes profits. Specifically, the BEA points out, 'Because national income is defined as the income of U.S. residents, its profits component includes income earned abroad by U.S. corporations and excludes income earned in the United States by foreigners.'”

The chart below shows corporate profits, per the BEA, divided by GDP. (You can substitute GNP but the result is virtually identical between the two measures.)

The current levels of profits, as a share of GDP, are at record levels. This is interesting because corporate profits should be a reflection of the underlying economic strength. However, in recent years, due to financial engineering, wage and employment suppression and increase in productivity, corporate profits have become extremely deviated.

This deviation begs the question of sustainability. Currently, according to the S&P website, reported corporate earnings are expected to grow by 20.26% in 2014, and by an additional 20.28% in 2015. In total, reported earnings are expected to grow by almost 50% (0.28/share as of 2013 to 7.50/share in 2015) over the next two years.

If we assume that these projections are accurate, and we assume a continued growth rate of 2% annually in the economy (as has been witness the average since 1999) we can put the current environment into perspective. The chart below shows real, inflation adjusted, GDP and reported earnings, both actual and estimates, through 2015.

I also notated the previous earnings trendline estimates that existed prior to each market peak.

The sustainability of corporate profits is dependent on two primary factors; sustained revenue growth and cost controls. From each dollar of sales is subtracted the operating costs of the business to achieve net profitability. The chart below shows the percentage change of sales, what happens at the top line of the income statement, as compared to actual earnings (reported and operating) growth.

Since 2000, each dollar of gross sales has been increased into more than in operating and reported profits through financial engineering and cost suppression. The next chart shows that the surge in corporate profitability in recent years is a result of a consistent reduction of both employment and wage growth. This has been achieved by increases in productivity, technology and offshoring of labor. However, it is important to note that benefits from such actions are finite.

As asset prices continue to surge higher in hopes of an "economic revival," the question of "sustainability" of corporate profitability looms large.

As John Hussman concludes:

"Given the economic landscape of recent years, large offsetting sectoral deficits and surpluses are not surprising, but they should not be taken as evidence that the long-term profitability of the corporate sector has permanently shifted higher. Stocks are not a claim to a few years of cash flows, but decades and decades of them. By pricing stocks as if current profits are representative of the indefinite future, investors have ensured themselves a rude awakening over time. Equity valuations are decidedly a long-term proposition, and from present levels, the implied long-term returns are quite dim.

The chart below (CPATAX/GNP) provides a good summary of the present situation, and a reasonable sense of what we expect for corporate profit growth over the coming several years."

As we know from repeatedly from history, extrapolated projections rarely happen. Could this time be different? Sure. However, believing that historical tendencies have evolved into a new paradigm will likely have the same results as playing leapfrog with a Unicorn.

There is mounting evidence, from valuations being paid in M&A deals, junk bond yields, margin debt and price extensions from long term means, "irrational exuberance" is once again returning to the financial markets. However, that does not mean that a mean reversion process in imminent. It was in 1996 when Alan Greenspan first uttered those famous words, it was 4 years later before investors regretted not paying attention them. It is likely that the same will be true this time. With the Federal Reserve still pushing liquidity into the markets, there is little to deter the "bullish bias" presently. However, as John noted above, investors that fail to heed the warning signs will likely ensure themselves a rude awakening over time.