A New York Fed research paper wonders What’s Keeping Millennials at Home? Is it Debt, Jobs, or Housing?

The paper says "it's a mystery" why the housing recovery did not have a bigger impact on millennials living at home.

The research paper, written by Zachary Bleemer, Meta Brown, Donghoon Lee, and Wilbert van der Klaauw notes correlations to debt, jobs and housing.

Yet, "student debt only explains about 10% of the increase in parental coresidence since 2004, with another 10% being explained by house prices during the mid-2000s".

I have the answer below, but first a few charts and notes on the charts.

Notes:

- CCP is the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Equifax-Sourced Consumer Credit Panel

- CPS is the Current Population Survey, a joint effort between the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Census Bureau

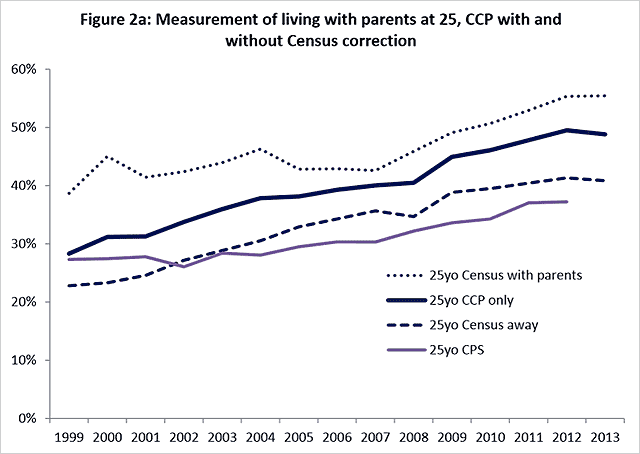

Coresidence 25-30 Year-Olds 1999-2013

Coresidence 25 Year-Olds 1999-2013 Census Corrected

Coresidence 30 Year-Olds 1999-2013 Census Corrected

Residence Arrangements 1999-2013

Student Debt Prevalence

Residence Choices and Economic Conditions

Fed Mystified, Puzzled

Trends towards increasing coresidence started well before the housing boom, and well before the great recession. Most student loan debt has been in the past few years, after the recovery began.

Student debt only explains 10% of the shift with another 10% attributable to housing prices. Here are a few paragraphs from the study that shows the puzzlement. Emphasis Mine.

Homeownership in the CCP declines from 2005 forward for 25 year olds, and from 2007 forward for 30 year olds, following steady or modestly increasing youth homeownership rates during the housing boom. Unlike the aggregate parental coresidence series, these homeownership trends suggest that early homeownership responded strongly to the events of the Great Recession. From this perspective, the decision to stay home with parents appears to be more closely tied to the student borrowing phenomenon, while housing choices (when not living with parents) appear to be more closely tied to economic conditions. The failure of young homeownership to track the housing market recovery, however, remains a puzzle.

The upward trend in coresidence with parents appears steady, and suggests little direct relationship to broad economic indicators such as unemployment measures and the house price index. This would seem to suggest that the decision to stay home with parents, or to move back in, relates more closely to the recent changes in the debt burden of higher education than to swings in youth labor markets and the cost of housing.

However, the analysis presented in Figure 7 is unsophisticated, and, as such, poses more questions than it resolves. In terms of the aggregate trends, the steady increase in coresidence with parents may reflect not a failure to respond to aggregate conditions, but offsetting effects of, for example, job and housing markets on residence decisions among the young. The failure of all youth residence decisions to reflect the recent recovery in employment and house prices remains a mystery.

What Did the Study Include?

I had to laugh when I saw pages of text and discussion that looked like this:

Xilt represents a vector of individual i , location l , period t characteristics the levels which may influence the residence choice of individual i at t+1. ... The vector Zc(i)l represents characteristics of individual i's cohort, c(i), and location l that do not vary by t ... The vector of state fixed effects is denoted σs(l). Idiosyncratic error εilt is clustered at the state level. ...

I cannot understand that, nor can anyone but 0.1% of true mathematical geeks. But I am quite certain the formula is mathematically sound.

Yet, at the same time, it is complete nonsense. The results actually speak for themselves. Such formulas only explain 20-40% of what is happening.

The model is clearly broken. Why?

Attitudes

The Fed believes all they have to do is push a button, and people will respond the way they want. The Fed got housing prices up, but only 10% of the response they expected.

Attitudes explain why. The Fed can and did make money available, but it cannot dictate where people spend it, or even if people spend it.

Here is a link to all the articles where I mentioned Attitudes. There are pages of references. It would behoove the Fed to read a few of them.

Clash of Generations

Unlike boomers and gen-Xers whose primary focus was on money and "getting ahead" lifestyles, millennials have more of a depression-era survival mentality coupled with a completely different set of values.

I have been writing about the implications of changing attitudes since at least 2008.

I wrote about the Clash of Generations in May 2014 in Boomers vs. Millennials: Attitude Change Will Disrupt Wall Street and Corporate America.

Major Attitude Shift

Flashback June 25, 2008: This is what I said about attitude changes in Peak Credit

Secular Attitude Change Underway

There is a secular attitude change happening right now. Boomers close to retirement are now (finally) scared to death as the equity in their houses has been vaporized. School age children are seeing homes foreclosed, and families destroyed over debt. The American consumer, who nearly everyone thinks will be back as soon as the economy picks up are mistaken.

Secular shifts like these come once in a lifetime. Sadly it's too late for many cash strapped boomers counting on equity in their houses for retirement.

Lessons of the Great Depression Forgotten

The lessons of their great grandfathers who lived in the great depression era were forgotten. Over time, everyone learned to ignore the dangers of debt, risk, and leverage. Belief in the Fed and the government to bail out any problem are ingrained. Bank failures are distant memories.

Anyone and everyone who wanted credit got it, and on the easiest of terms: subprime, pay option arms, reckless leverage, and covenant lite debt and toggle bonds that allowed debt to be paid back with more debt. That's what it takes to hit a peak.

Peak Credit

Peak credit has been reached. That final wave of consumer recklessness created the exact conditions required for its own destruction. The housing bubble orgy was the last hurrah. It is not coming back and there will be no bigger bubble to replace it. Consumers and banks have both been burnt, and attitudes have changed.

It took nearly 80 years for people to get as reckless as they did in 1929. 80 years! Few are still alive that went through the great depression. No one listened to them. That is the nature of the game. The odds of a significant bout of inflation now are about the same as they were in 1929. Next to none.

Children whose parents are being destroyed by debt now, will keep those memories for a long time.

Social and Stock Market Impacts

I was wrong about peak credit but everything else I stated was pretty much spot on, including price inflation.

Although peak credit has been surpassed, a substantial portion of the rise in credit is in the form of student loans that cannot and will not be paid back without bailouts.

Importantly, millennial attitudes towards cars and other material goods is not the same as their parents.

As boomers retire, they will need to draw down on both their stock market portfolios and their savings (assuming they have either).

Millennials will assist aging boomers via taxation and by overpaying for Obamacare. Higher taxes coupled with increasing time commitments to help care for aging parents will take a toll. And because boomers live longer than ever, the economic drain and time commitment from millennials will increase every year.

This has downward implications on the economy and the markets, especially in light of millennial-mistrust in stocks and the massive amount of student debt many of them carry.

What Did the Study Include vs. What it Didn't

The study looked at debt, jobs, and housing.

"Student debt only explains about 10% of the increase in parental coresidence since 2004, with another 10% being explained by house prices during the mid-2000s".

The Study missed changing social attitudes and the demographics of aging parents! Attitudes and demographics explains the 80% miss.