It’s Not That Simple

In my previous article Why the Bakken Boomed, I discussed the shale oil boom that has had such a dramatic impact in North Dakota’s Williston Basin over the past decade. But throughout the U.S. shale boom there have been those who doubted that the production gains would prove anything other than fleeting. Those doubts were grounded in the fact that shale oil production is more complex and expensive than conventional oil production, and the fact that cash flow has been consistently negative for virtually all shale oil producers.

While the doubts are based on fact, the story is more complex than it may appear. Isn’t that always the case though? Things are never quite as simple as they seem. Superficially, the narrative for many has been “Shale oil isn’t economical. The wells deplete too quickly. Just look at the negative cash flow.” But it’s just not quite that simple. Let’s dig a little deeper to gain a better understanding of what has happened, what is happening, and what is likely to happen moving forward.

The Boom-Bust Cycle for Dummies

First it’s important to understand that the oil industry is cyclical, and more importantly to understand the reason that it is cyclical. The long history of the oil industry has been one of boom and bust cycles. During the booms we hear about windfall profits, but during the downward part of the cycle, oil companies lose a lot of money and many people lose their jobs.

See related: Interview with Robert Rapier on possibility of $20 oil

So why is the oil industry cyclical? It’s not complex. It is a function of the capital-intensity of the business, and the multi-year lag time in getting projects executed. If you just want the executive summary, here it is. I have arbitrarily started this at the bottom of the cycle, and the 5 stages I have described here could be described at a more granular level with more stages:

- Stage 1: At the bottom of the cycle, there is excess oil supply which results in low oil prices and a period of under-investment by the oil industry. Low prices also stimulate higher demand.

- Stage 2: Demand grows faster than supply, leading to a tightening supply/demand balance. Oil prices begin to rise.

- Stage 3: Rising oil prices mean oil companies start making money, and they ramp up investments in new projects. The higher prices rise and the longer they remain high, the greater the investments. New oil plays become economical, and new oil companies are formed. Some of these companies employ a lot of financial leverage, which is OK until…

- Stage 4: Higher prices curb demand growth, and new projects begin to come online. Production growth begins to outstrip demand growth.

- Stage 5: Prices collapse, and the oil industry contracts as capital expenditures are slashed. We return to Stage 1. The cycle is complete.

Keep in mind that some of these steps overlap in time, partially because the oil industry is made up of so many different companies with many different management styles. One company may still be investing heavily while another has already slashed spending in anticipation of falling prices.

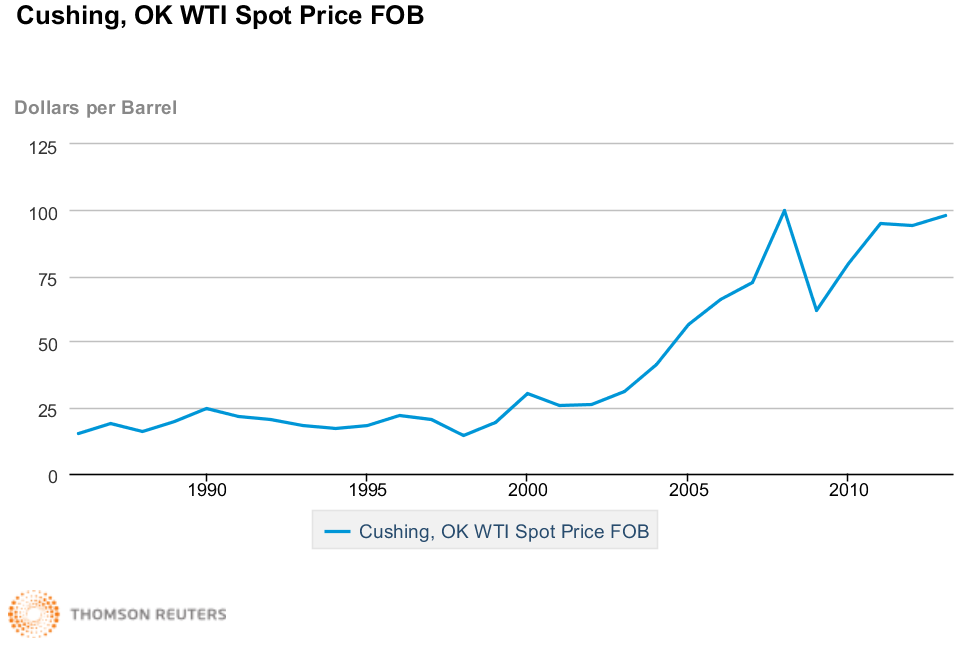

We were at Stage 1 of the cycle in the late 1990s, when oil prices were bouncing between $20 and $30/bbl. In response to low prices, oil companies were conservative in their capital expenditures leading up to the early 2000s. In 2002 the price of oil slowly began to rise as demand growth outpaced new supplies and reduced the world’s spare capacity cushion. We were entering Stage 2.

Source: Energy Information Administration

We spent the early part of the past decade in Stage 2, but then most of 2005-2010 was spent in Stage 3. In 2005, the price of West Texas Intermediate (WTI) averaged .64, rising to an average of .05/bbl in 2006, .34/bbl in 2007, .67/bbl in 2008, but then falling back to .95/bbl in 2009.

Demand in the developed world started to decline in earnest in 2008. This marked the early stages of Stage 4, which was drawn out because of strong demand growth in developing countries (which kept global demand growing). But new production was coming online at a rapid pace in response to 0/bbl oil, and a supply cushion began to once again expand. In mid-2014, we entered Stage 5 as the price of oil began to collapse.

Negative Cash Flow — Losing Money or Reinvesting in the Business?

In 2005, most oil companies generated solid operating cash flow — defined as the cash generated by a company related to core operations. But as the shale boom accelerated, and with prices remaining high, oil companies went on a spending spree to get new projects implemented. Prices got so high that oil companies were investing every cent they could get their hands on to capitalize on the opportunity.

It’s easy to understand why they do it. Imagine you are running a business, and making very hefty margins on the products you are selling. You would likely want to plow your profits back into the business to grow sales as long as the margins are strong. If you are getting higher prices for your products each year, you are going to continue to plow that money back into growing the business. But this may very well put your business in a negative cash flow position even when prices are high.

As long as margins are good, you can grow your business rapidly. But what happens if prices collapse? It depends. If you grew by highly leveraging your business — in other words if you borrowed lots of money to grow it even faster – then you could be in trouble. If, on the other hand you don’t have a lot of debt to service and are able to slash your capital spending, you may be able to generate profits even though prices have collapsed.

As the spending spree ensued, cash flow turned solidly negative by 2009, even though the price of oil was higher than it was in 2005. A recent graphic by Oppenheimer tells the tale:

When oil prices began to fall in mid-2014, companies began slashing capital expenditures. But they are slashing from capital expenditures that a year earlier were based on 0/bbl oil. Oil prices have fallen so far, so fast that essentially all oil and gas companies are still in a negative cash flow position despite the cuts they have made (except of course the refiners, who benefit from low oil prices). And they are slashing based on projections of where they think oil prices will be in the future. Different companies will have different ideas of where oil prices are headed and different levels of indebtedness, so they will naturally differ in how aggressively they will prune capital expenditures.

Shale Oil Economics

History argues that, even if oil prices remain near /bbl for an extended period of time, some companies will be able to rein in costs enough to generate free cash flow as they did in 2005. Of course the counterargument is that it costs more to produce oil in 2015 than it did in 2005, when companies had positive cash flow with WTI at .64/bbl. After all, it took higher prices to enable the shale oil boom, and therefore it stands to reason that it will take higher prices to keep it going.

Let’s first consider the economics of producing oil from a shale play. (For a more detailed explanation, see Art Berman’s recent Forbes article Only 1% Of The Bakken Play Breaks Even At Current Oil Prices).

Broadly speaking, the economics of oil production hinge on the cost to drill and complete the well, and the amount of oil, gas, and natural gas liquids that are obtained from the well. There are also other expenses involved, such as operating costs, taxes, exploration costs, etc. But let’s focus on the cost to drill and amount of oil produced.

If an oil producer spends million to drill and complete a well, but only recovers 100,000 barrels of oil from that well, then that’s /bbl just on the drilling and completion costs. If, hypothetically they could produce 1 million barrels from that well, then it’s just /bbl on drilling and completion costs. Thus, the amount of oil ultimately recovered has a huge impact on the cost of production.

In the early days of the shale oil learning curve, the wells were more expensive to drill and complete relative to the production levels that were being achieved. As operators gained more experience by experimenting with the number of fracking stages, the amount of sand, etc., they lowered their cost of production. A 2009 filing by Brigham Exploration — later acquired by Statoil (NYSE: STO) — demonstrates how oil well economics improved as more hydraulic fracturing stages were introduced to horizontal wells:

Source: Brigham Exploration SEC filing

This shows that within four years or so this company was able to reduce the cost of producing a barrel of oil from shale formations by more than /barrel of oil equivalent (BOE). (Note that this is only the cost to produce; it doesn’t include operating costs, etc.). Thus, what may have only been economical at 0/bbl in 2006 could have been economical at /bbl by 2010. By 2014, many were claiming that the break even cost had fallen to /bbl or even lower.

But that’s an industry wide estimate. As Art Berman explains in his article, there are a few Bakken wells that are breaking even with Bakken oil prices in the low s (and WTI in the mid-s). But those wells are the most productive wells in the Bakken Formation, which drives down the cost per barrel for drilling and completion. Industry wide, it’s probably going to take WTI prices of at least /bbl before the average Bakken well breaks even. Of course that’s an average; some operators will still be in trouble at that price while others will start to generate positive cash flow.

Fast Depletion or Fast Production?

So what about the notion that fracked wells deplete too quickly, and that is why they can’t be economical? I have heard this justification repeated many times, but again reality is more complex. First, it isn’t a mystery to the companies drilling these wells that they deplete quickly. What they are interested in is the estimated ultimate recovery (EUR). If you are familiar with the time value of money, you would like to have your investment paid back as quickly as possible. So if I have a well that is going to produce 500,000 barrels during its lifetime, do I want a slow and steady depletion to zero? No. As an operator, I want to get that oil out as quickly as I can without damaging the well and reducing its ultimate production. Where some see fast depletion as a problem, another way to look at it is that you got most of the available oil out quickly. (Note that some operators are experimenting with throttling wells early on to determine whether that increases the EUR).

Conclusions

The history of the oil industry has been one of cycles, from nearly the beginning of the industry in the 1850s through today. In the down cycle that we are currently experiencing, demand rises due to low prices, even as oil producers begin to cut capital expenditures. U.S. shale production has already begun to decline as very little shale oil production is currently profitable. The end result is very predictable, even if the timing is not. While there is broad agreement that a great deal of U.S. oil production is currently unprofitable, some feel like oil prices need to fall further to make a bigger dent in production because crude oil inventories are still quite high. I feel like with the continued growth in global demand, we can already see the supply/demand picture tightening on the horizon. When that becomes broadly obvious, oil prices will again rise, bringing profits to the industry and higher capital spending on new projects. How long that process takes will determine how many oil companies are left standing to reap those profits.