The history of the U.S. dollar is closely linked to U.S. involvement in a series of wars. The Bretton Woods Accord and the resulting world reserve currency status of the U.S. dollar were both byproducts of World War II (1939-1945). The Korean War (1950-1953) was followed six years later by the Vietnam War (1959-1975) which led to the end of the Bretton Woods system. Unfettered by the constraint of gold backing after 1971, the U.S. dollar became a weapon in the Cold War (1945–1991) between the U.S. and the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (U.S.S.R.). Each war corresponded with an increase in the U.S. money supply. The Gulf War (1990-1991) was followed by wars in Afghanistan, beginning in 2001, and in Iraq, beginning in 2003, and, simultaneously, by the U.S.-led War on Terror that began in 2001. Like the wars that came before them, the recent staccato of U.S. wars is correlated with increases in the U.S. money supply. The Iraq war, for example, is estimated to have cost as much as $4 trillion.

The loss of value in the U.S. dollar caused by excessive expansion of the money supply, together with rising demand for raw materials from emerging economies, has led to permanently higher global commodity prices. Higher crude oil prices, in particular, have put pressure on the U.S. economy, which is putatively in a gradual recovery from the recession that began in 2007. At the same time, international trade has begun to move away from the U.S. dollar, threatening its world reserve currency status. Given the history of the U.S. dollar, it seems likely that an eventual end of the U.S. dollar’s reign as the world reserve currency will be marked by war.

U.S. politicians are clamoring for war with Iran, the third largest oil exporter in the world. Iran refuses to sell its oil for U.S. dollars. If Iranian oil were traded in U.S. dollars, it would moderate the U.S. dollar price of crude oil and ease pressure on the U.S. economy, as well as extend the world reserve currency status of the U.S. dollar and give the U.S. economic leverage over consumers of Iranian oil, which include China and India.

The U.S. news media is preparing the American public for a war with Iran with reports about the dangers of Iran becoming a nuclear power. Television news reports have speculated that Iran would immediately wipe out Israel if it obtained a nuclear weapon, despite the fact that a thermonuclear exchange would wipe out Iran. It has also been reported that Iran might carry out nuclear strikes on U.S. soil using intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), although Iran possesses neither nuclear warheads nor ICBMs. In fact, there is no evidence that Iran is currently building a nuclear weapon. One concern that is valid, however, is that no nuclear power has ever been invaded in a conventional war.

Forged in the Fire of War

The approaching end of World War II led to the creation of the Bretton Woods system in July 1944, although fighting in Europe and in the Pacific continued into 1945. The U.S. dollar, which was convertible into gold, became the dominant mechanism for international trade settlement. The price of gold was set to the pre-war price of $35 per troy ounce, which was deflationary at the time. There was nothing in the Bretton Woods Accord, however, that prevented the U.S. from issuing more currency than was backed by gold other than the threat of a run on U.S. gold reserves.

The Bretton Woods system worked as intended for roughly 17 years. The London gold market, which had been closed during World War II, reopened in 1954. By 1961, upward pressure on the price of gold prompted the establishment of the London Gold Pool by the U.S. Federal Reserve and major European central banks (including the central banks of the United Kingdom, Belgium, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Switzerland and West Germany). The London Gold Pool defended the $35 per troy ounce price through interventions in the London gold market, but upward pressure on the price of gold grew. In July of 1962, Americans were forbidden by then president Kennedy to own gold abroad by Executive Order 11037. In a 1965 press conference, then president of France, Charles de Gaulle publicly denounced the U.S. for abusing the world reserve currency status of the U.S. dollar. The London Gold Pool collapsed in March of 1968 after France withdrew from the group setting off a surge in gold demand that caused the London gold market to shut down for a two week period.

By 1971, substantially due to the cost of the Vietnam War, the U.S. had leveraged its gold reserves to the breaking point. The expansion of the U.S. money supply caused the U.S. Consumer Price Index (CPI) to increase by more than 6% in 1970 and it remained above 4% in 1971. When U.S. President Nixon “closed the gold window” in August 1971 and instituted price controls, the Bretton Woods system ended and an ad hoc floating exchange system resulted. From their peak during World War II to 1971, U.S. gold holdings fell from approximately 20,205 tonnes to approximately 8,134 tonnes. In February 1973, the U.S. devalued the dollar and raised the official dollar price of gold to $42.22 per troy ounce. By June of the same year, the market price in London had skyrocketed to more than $120 per ounce.

Although CPI inflation was below 4% at the start of 1973, it rapidly accelerated, reaching 9% at the start of 1974. With the last vestiges of gold backing having been removed from the U.S. dollar, Americans were once again allowed to own gold as a hedge against inflation. Against a backdrop of runaway U.S. dollar inflation, Arab members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), along with Egypt, Syria and Tunisia proclaimed an oil embargo in October of 1974. Officially, U.S. support of Israel in the Yom Kippur War was the reason for the embargo, but it was also a challenge to the un-backed U.S. dollar’s position as the world reserve currency, i.e., as an exclusive medium for crude oil sales.

After the end of the Yom Kippur War in 1974, OPEC members, including Iran before the Iranian Revolution in 1979, began to accumulate hundreds of billions of devalued U.S. dollars due to current account surpluses linked to rising oil prices. Arab “petrodollars” were recycled into US Treasuries, invested in financial markets around the world and loaned to commercial banks.

By 1979, oil prices had roughly quadrupled and the price of gold was increasing rapidly. Then Federal Reserve Chairman, Paul Volcker raised the Federal Reserve’s funds rate to an average of 11.2% in 1979. Nonetheless, in 1980 CPI inflation soared to 13.5% and the stagnant U.S. economy also slipped into recession. The price of gold hit 0 per troy ounce and the price oil averaged .42 per barrel, more than ten times the average price of .60 per barrel less than a decade before in 1971.

In a desperate bid to save the U.S. dollar, Volcker increased the funds rate to an unprecedented 20% in mid 1981, pushing the prime interest rate to a usurious 21.5% by the middle of 1982. Finally, Volcker’s radical intervention slowed the rate of CPI inflation and restored confidence in the U.S. dollar. It also brought the price of crude oil down and smashed the prices of gold and silver.

The Committee to Flood the World

Post Volcker, the Federal Reserve’s dilemma was how to bring down interest rates while managing the CPI independent of increases in the money supply, e.g., to neutralize the Triffin Dilemma (a conflict between domestic monetary policy and the demands placed on a currency by international trade) and to support U.S. federal government borrowing during the Cold War. The first key to the solution was to look at inflation strictly in terms of its effects on prices and not as an increase in the money supply, which is a function of interest rates. When interest rates are low, prices tend to rise because the money supply expands more quickly, thus the second key was to de-couple prices and interest rates. The third and final key was to manage the psychology of the consumer in terms of inflation expectations. While altering the CPI to reflect relatively stable prices and managing consumer inflation expectations were easily accomplished, de-coupling prices and interest rates was a more difficult problem because the prices of global commodities were not entirely under U.S. control. Ultimately, managing the CPI required managing global commodity prices, especially the price of crude oil.

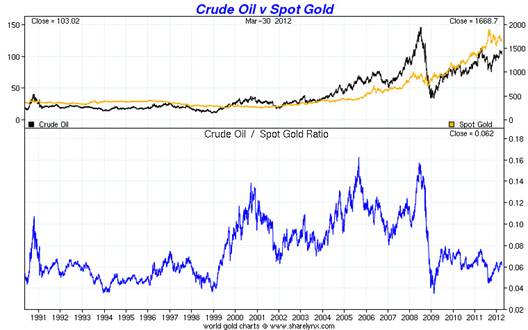

A crucial breakthrough came in 1988. The article, “Gibson’s Paradox and the Gold Standard” by Robert B. Barsky and Lawrence (“Larry”) H. Summers in the Journal of Political Economy, showed that the price of gold was inversely correlated to interest rates. Since gold is not industrially consumed in significant quantities, the price of gold changes relative to the value of major currencies. Specifically, the price of gold had proven to be a barometer of U.S. dollar inflation after 1971. What was more important was that the prices of gold and crude oil tended to correlate. The implication of Gibson’s Paradox was that interest rates could remain low as long as the price of gold did not rise. If interest rates could remain low without causing an accelerating increase in the CPI, as had happened in the 1970s, the money supply could be expanded indefinitely.

A few years after Alan Greenspan took the helm as Chairman of the Federal Reserve in 1987, interest rates were slashed and the resulting increase in the U.S. money supply began to pull away from the increase in the CPI. For roughly two decades, beginning with Volcker’s success in the early 1980s, the price of gold declined while oil prices remained relatively stable, despite the fact that interest rates had come down.

The innovations in U.S. monetary policy developed principally by Summers and Greenspan helped to make it possible for the United States to up the ante in the Cold War, which ended with the collapse of the U.S.S.R. in 1991. Setting aside all other issues, the U.S.S.R. had arguably been spent into oblivion by the U.S. The fall of the U.S.S.R. seemed to guarantee the hegemony of the U.S. dollar for decades to come.

During the 1990s, Greenspan, together with Larry Summers, who was Deputy Secretary of the U.S. Treasury under Robert Ruben at the time, championed financial deregulation. Confident in their ideas, the so-called “committee to save the world” prevented regulation of over the counter (OTC) derivatives and succeeded in effectively repealing the Banking Act of 1933 (the Glass–Steagall Act).

In hindsight, Greenspan held interest rates too low for too long in the 1990s resulting in the dot-com bubble. The bursting of the dot-com bubble was a shot across the bow of the “committee to save the world” but the warning went unheeded. The Federal Reserve moderated the downturn beginning in 2000 by lowering interest rates and they remained low. U.S. banks took advantage of deregulation and low interest rates to speculate and to increase their leverage, especially in the mortgage market, while hedging the additional risks in the fast growing OTC derivatives market. As the resulting real estate bubble grew, the notional value of OTC derivatives exceeded 0 trillion on a global basis (more than ten times world GDP) and financial services industry profits expanded to 40% of S&P 500 business profits.

The price of gold had begun to move up after having made a historic low in June of 2001 and, in 2006, the price of crude oil began to rise at an accelerating rate revealing a fundamental flaw of de-coupling interest rates from prices. The flaw was that the Federal Reserve had absolutely no control over the flow of increased liquidity resulting from its policies. The “committee to save the world” was flooding the world with cheap U.S. dollars. Increased liquidity linked to low interest rates was fueling unprecedented levels of financial speculation and increasing the risk and magnitude of asset price bubbles, such as the dot-com bubble and the real estate bubble. To make matters worse, excessive monetary expansion was weakening confidence in the U.S. dollar.

Pressured by rising oil prices, the U.S. economy began to roll over in 2007. As the U.S. housing bubble began to burst, beginning with sub-prime loans, the price of West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil hit an all-time high of 5 in June 2008. Roughly four months later, a financial crisis far larger than that of 1929 began to take place, i.e., the bursting of the largest credit bubble and monetary expansion in the history of the world. In October 2008 Greenspan testified before the U.S. Congress saying “…I found a flaw…in the model that I perceived is the critical functioning structure that defines how the world works…”

Quantifying the Crisis

The policy responses of the U.S. federal government and of the Federal Reserve (under Chairman Ben S. Bernanke since 2005) to the financial crisis and to the so-called Great Recession were radically inflationary. The Federal Reserve loaned trillion to financial institutions worldwide and .77 trillion to U.S. banks and corporations. The Federal Reserve also purchased roughly trillion worth of toxic mortgage backed securities (MBS) from banks and monetized a total of roughly 0 billion of U.S. federal debt, expanding its balance sheet from 0 billion before the crisis to .7 trillion.

In the face of the most severe economic decline since the Great Depression, the U.S. federal government embarked on a 0 billion economic stimulus plan, despite the fact that tax revenues were falling. In addition to an initial 0 billion bailout package, government sponsored entities Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were taken into receivership, making the U.S. federal government liable for roughly trillion of mortgage debt. In 2009, the total liabilities of the federal government were estimated to be as high as .7 trillion by then Special Inspector General for the Troubled Asset Relief Program (SIGTARP), Neil Barofsky. As a result, U.S. federal government debt increased sharply and, in 2011, the U.S. credit rating was downgraded for the first time in history.

Loss of value in the U.S. dollar, caused by radically inflationary monetary policies, set off a global currency war in 2009 and pushed global commodity prices higher than they would otherwise have been. Higher crude oil prices, despite lower demand, slowed economic recovery. At the same time, high debt levels, bank bailouts, soaring government budget deficits and falling tax revenues produced a sovereign debt crisis in Europe. Although the focus of the still developing sovereign debt crisis remains on Europe, the skyrocketing debt and unfunded Social Security and Medicare liabilities of the U.S. federal government, estimated to be more than trillion, foreshadow a similar crisis in America.

The Trap of Financial Warfare

One of the key reasons why the U.S. has yet to experience a sovereign debt crisis is that the world reserve currency status of the U.S. dollar supports demand for the U.S. dollar and for U.S. federal government debt. However, the U.S. dollar is in the process of gradually losing its world reserve currency status. Global trade is fragmenting into increasingly autonomous trading blocks defined by currencies and trade relations, such as the BRIC nations (Brazil, Russia, India and China), together with South Africa.

Demand from emerging economies, particularly China, is placing steady upward pressure on the price of crude oil. Higher oil prices resulting from a combination of a weaker U.S. dollar and increased global demand threaten to push the U.S. economy back into recession. Setting aside flat to declining supplies of sweet light crude oil (Peak Oil), the fact that the price of gold has risen roughly 500% in a single decade suggests much higher oil prices in the future.

Iran, which is the world’s third largest oil exporter and a major supplier of oil to China, lies outside of U.S. control. Iran refuses to sell oil for U.S. dollars, partly as a consequence of the overthrow of the democratically elected government of Iran in 1953, orchestrated by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, and partly as a consequence of current U.S. policies in the Middle East.

In March of 2012, the U.S. unilaterally removed Iran from the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) system, effectively cutting it off from world commerce. However, wielding the U.S. dollar’s world reserve currency status as a blunt instrument could be counterproductive in the current international climate. If the U.S. dollar were to lose its world reserve currency status over a short period of time, a U.S. sovereign debt crisis would be certain and a catastrophic collapse of the U.S. dollar, i.e., hyperinflation, would be possible.

Having taken a decision to act unilaterally against Iran, the U.S. may be forced to resort to more extreme measures if the world reserve currency status of the U.S. dollar begins to break down. Of course, the U.S. does not control the oil trade solely through financial means. With Israel as a close ally, Iraq and Afghanistan occupied by U.S. forces, close ties with Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar and other Middle Eastern countries, Iran is surrounded by more than 40 U.S. military installations.

A successful invasion of Iran would eliminate the largest non U.S. dollar oil exporter, delaying the breakdown of the U.S. dollar’s status as the world reserve currency. Although a war with Iran would cause a spike in oil prices, U.S. control of Iran’s oil would increase the supply of oil available for purchase in U.S. dollars, which would bring the U.S. dollar price of oil down and enhance the ability of the U.S. to manage the price of oil to meet the needs of the U.S. economy. Controlling a major supplier of crude oil to China and India would give the U.S. additional leverage to support the U.S. dollar and U.S. debt, as well as a means of influencing the policies and economic growth of the two largest nations. The option of invasion, however, may be time limited. If Iran were to eventually obtain nuclear weapons, the risks involved in a U.S. invasion would escalate.

As an alternative to invasion, a limited U.S. military action might involve surgical strikes on Iranian nuclear research and power facilities, as well as on Iranian military forces that pose a threat to the U.S. military. Destroying Iranian nuclear facilities and suppressing potential counterstrikes also suggests neutralizing Iran’s threat of disrupting the oil trade by closing the Straight of Hormuz. Thus, a limited U.S. military action would involve military operations on a scale not seen since the invasion of Iraq in 2003.

A limited U.S. military action might leave a weakened Iranian regime in place after the conflict and reignite the moderate, pro-democracy Green Movement that was brutally suppressed in 2009. Regime change from within might restore democracy to Iran after twenty six years of U.S.-imposed monarchy and more than three decades of quasi-democratic religious oligarchy. However, regime change is unlikely to result in the sale of Iranian oil in U.S. dollars or to extend the reign of the U.S. dollar as the world reserve currency. A preemptive strike by the U.S. could also strengthen political support for the current Iranian regime.

There seems to be no political will in Washington D.C. to change course from a U.S. military conflict with Iran, despite the fact that a U.S. attack on Iran will increase anti-U.S. sentiment in the region and amplify the Islamic extremist dimension of the U.S.-led War on Terror. The drumbeat to war in the U.S. news media is loud and clear and, if history is any guide, the U.S. will soon, e.g., after the 2012 presidential election, “cry havoc and let slip the dogs of war”.