Guest post by Norman Mogil

Ever since the 2008 financial crisis, there has been a persistent shortage of high-quality government debt. More than just a safe haven in times of financial stress—the so-called 'flight to quality'—the supply of high-quality sovereign debt has been steadily shrinking. This shortage became acutely apparent with the results of the Brexit referendum as investors worldwide bid up bond prices to the point where most long-term bond yields reached historic lows in the US, UK, Germany, and Japan. Brexit only exacerbated a shortage problem that bond investors have had to contend with for nearly a decade. The current squeeze in supply is just the latest manifestation of this wider issue in today's financial markets.

Read Shilling: World Facing High Probability of Panic Deflation

To claim that there is a shortage of government debt must seem counter-intuitive to many readers. After all, there is no end of studies demonstrating that major economies have record high government debt-to-GDP ratios, signifying that there is too much debt, not too little. Many critics call for governments everywhere to issue less debt, arguing that such high levels of debt ratios contribute to sluggish growth if not outright stagnation. European governments continue to exercise spending restraints and, in general, austerity is the byword throughout the industrialized world. Governments have been very reluctant to open up their coffers by issuing more debt to fund expenditures.

However, a case can be made for more government debt. In a recent article, The World Needs More US Government Debt former FOMC member Narayana Kocherlakota argued this case, succinctly, when he wrote:

But scarcity is not about supply alone. In the wake of the financial crisis, households and businesses are demanding more safe assets to protect themselves against sudden downturns. Similarly, regulators are requiring banks to hold more safe assets. Market prices tell us that the government needs to produce more safety in order to meet this increased demand. The inadequate provision of safe assets also has profound implications for financial stability. Without enough Treasury bonds to go around, investors “reach for yield” by buying apparently safe securities from the private sector—if such behavior becomes widespread, it can create systemic risks that tip the financial system into crisis.

To better understand how bonds became scarcer, we begin by looking at who is buying government debt and why.

The Expanding Role of Central Banks

As the Federal Reserve sought ways to stimulate the economy, it became the first major central bank to start a bond-purchase program—Quantitative Easing (QE)—soon after the Bank of England (BoE), the Bank of Japan (BoJ) and, most recently, the European Central Bank (ECB) developed their own versions of QE ( Chart 1). The US Fed holds nearly 20 percent of all Federal government debt; the BoJ owns over 30 percent; the BoE, 25 percent; and, the ECB has so far bought about 15 percent of German debt. The Fed is no longer purchasing debt, while the other central banks continue with their QE programs.

The Fed increased its balance sheet dramatically from about 0 billion to over .4 trillion under three QE programs. Although the Fed no longer actively purchases government bonds, it appears in no hurry to release those bonds into the marketplace, instead allowing the bonds to mature fully over time.

Read also Dr. Keith Barron on Helicopter Drops, Gold, and Brexit

Over 40 percent of outstanding US Treasuries are held by foreign central banks, sovereign wealth funds, and other institutions. China and Japan together account for about 12 percent. As the US runs current account deficits with its major trading partners, the excess in US dollars is recycled into purchases of US Treasuries. More importantly, many central banks, especially those in emerging countries, have purchased Treasuries in increasing amounts and holding them to shore up their balance sheets and to provide needed foreign exchange reserves. In sum, Treasuries are been soaked up by the US domestic and foreign entities as part of a worldwide push to strengthen balances in the private and public sectors in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis.

The ECB and the BoJ both continue with very aggressive bond purchasing programs. The BoE may be forced to expand its current program in response to the fallout from UK voters opting to leave the EU. The ECB came late to the game of bond purchases, starting in 2015, some six years after the US first implemented QE. Initially, the ECB embarked on a program of purchasing government debt at a rate of 50 billion euros per month. But as the supply of qualified government debt diminished, the ECB increased its bond purchasing program to included corporate. Overall, the ECB program now soaks up about 80 billion euros a month of high-quality debt. Speculation is ripe that the ECB will do more bond purchasing in the wake of the Brexit vote. Turning to Japan, the BoJ has long been a huge purchaser of domestic government bonds(JGBs). Over the next four years, the BoJ is expected to own over 60 percent of all outstanding JGBs, the highest of any country.

Growing Domestic Needs for Treasuries

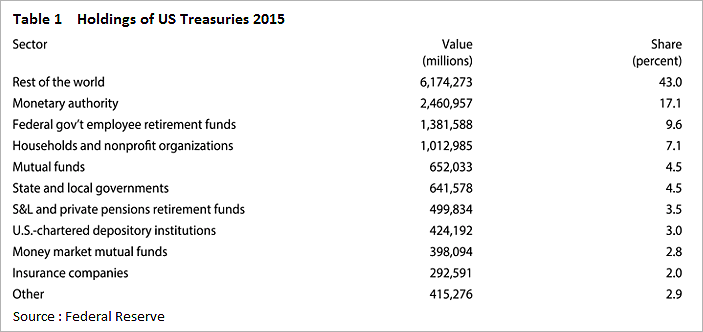

Domestically, major holders of Treasuries include the Federal government and state & local pension plans (Table 1). These plans will require additional risk-free Treasuries to meet longer term obligations. The US charted banks have significantly increased their holdings of Treasuries and Agency debt as a means of strengthening their balance sheets. From 2013 to the present, commercial banks increased holdings of Treasuries by 30 percent. Finally, private pension funds and the life insurance companies hold approximately 6 percent of their assets in Treasuries. Industry analysts argue that proportion is inadequate to meet future liabilities and it is expected that these institutions need to double their holdings to satisfy future income requirements. In short, government bonds will be a strong asset class from here on out as these institutions re-balance their portfolios to meet long run requirements.

The Phenomenon of Negative Interest Rates

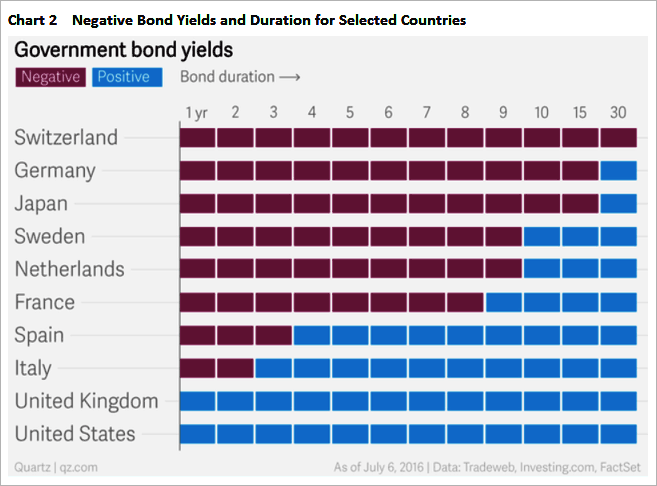

One does not have to look any further than the exploding market for negative interest rate bonds to find convincing proof of a bond shortage. Today, negative interest rate bonds total over 12 trillion USD in Europe and Japan (Chart 2). More importantly, the average duration of these bonds has increased remarkably just within the past year. Negative yields extend out to 10+ years in Germany, 15 years in Japan and even as far as 30 years in Switzerland (see Understanding Negative Interest Rates for more).

You may also like Bert Dohmen: China Still the Greatest Threat to Global Markets

Not surprisingly, central banks themselves are having trouble finding all the bonds they need. For example, the ECB is not permitted to buy bonds with a yield lower than its deposit rate of minus 0.4 percent, thus excluding many billions of euro-dominated bonds issued by Switzerland, Germany, France, Netherlands, and Sweden. In other words, there is a real squeeze on positive-yielding safe haven bonds.

Vanishing Credit Quality and Liquidity

Since the emergence of the debt crisis in Europe starting in 2012, there has been a wave of national debt downgrades. Bank of America Merrill Lynch estimates that the share of bonds with the three highest credit ratings has dropped to 51 percent of all debt tracked by the bank’s world sovereign bond index from 84 percent in 2011. With so many institutions restricted from purchasing anything less than high-quality bonds, managers are facing a smaller and smaller market in which to participate. Credit-worthiness comes into play in the very large repo loan market where high-quality debt is used as short-term collateral by hedge funds, money markets, private equity and other lending groups. It is estimated that the volume of repo loans using Treasury debt has nearly halved since the financial crisis of 2008.

On the issue of liquidity, there have been system-wide reductions, even in the case of the US Treasury market, considered to be the most liquid of all bond markets. Regulatory changes post-2008 have made bond dealers less willing to hold inventory and facilitate trades. Bond trading desks have slashed inventories in response to regulations such as Basel III and the Volcker Rule. Hence, primary dealers have reduced their US debt holdings by as much as 80 percent according to Bloomberg.com estimates.

These liquidity developments have prompted Barry Eichengreen of UC Berkeley to argue that “international liquidity has plummeted from nearly 60 percent of global GDP in 2009 to barely 30 percent today.” Recent auctions for US Treasuries feature large oversubscriptions, and this has driven yields lower. There is more than just a temporary flight to safety to the quality debt; there appears to be a major shift in asset preference in favor of high-quality debt issued by the US and other major countries at a time when the supply of that debt is not keeping with demand.

Outlook for Supply

In a recent report, Bank of America Merrill Lynch said that "the world is running out of positive-yielding safe-haven bonds.” The looming shortage has implications in many segments of the fixed income market. Every indication points to a worsening of the supply shortage of high-quality bonds. In the US, the 2016 Federal deficit is expected to be lower than the previous year by some 25 percent. To finance this lower deficit, the Treasury has opted to issue more bills instead of bonds as a means of lowering interest costs. This combination will exacerbate the shortage situation and will most likely keep long rates down at these current levels.

In Europe, the ECB is running out of qualified government bonds to purchase in the wake of a growing segment of the market having gone deep into negative territory. It has had to resort to buying corporate bonds to satisfy its purchasing objectives. There is no sign that Euroland will ease up on its austerity program and we can expect a tight supply of new government issuance in 2016-17. Japan continues to wallow in deflation and the BoJ continues to be under pressure to step up its bond purchasing program, driving longer dated yields ever lower. From a supply perspective alone, we can expect that long-term rates will be kept at these historic low levels.