Summary: It's true that corporations buying their own shares (buybacks) represents a large source of demand for equities and have helped push asset prices higher.

But much of what is believed about buybacks is a myth. There is much more to share appreciation than buybacks. EPS growth is overwhelmingly driven by higher profits, not share reduction. Buybacks are not a result of ZIRP or QE. Companies are not, as a whole, under investing in manufacturing or R&D or other sources of future growth because of buybacks.

Buybacks are widely vilified and greatly misunderstood. This post will try to separate the facts from the myths.

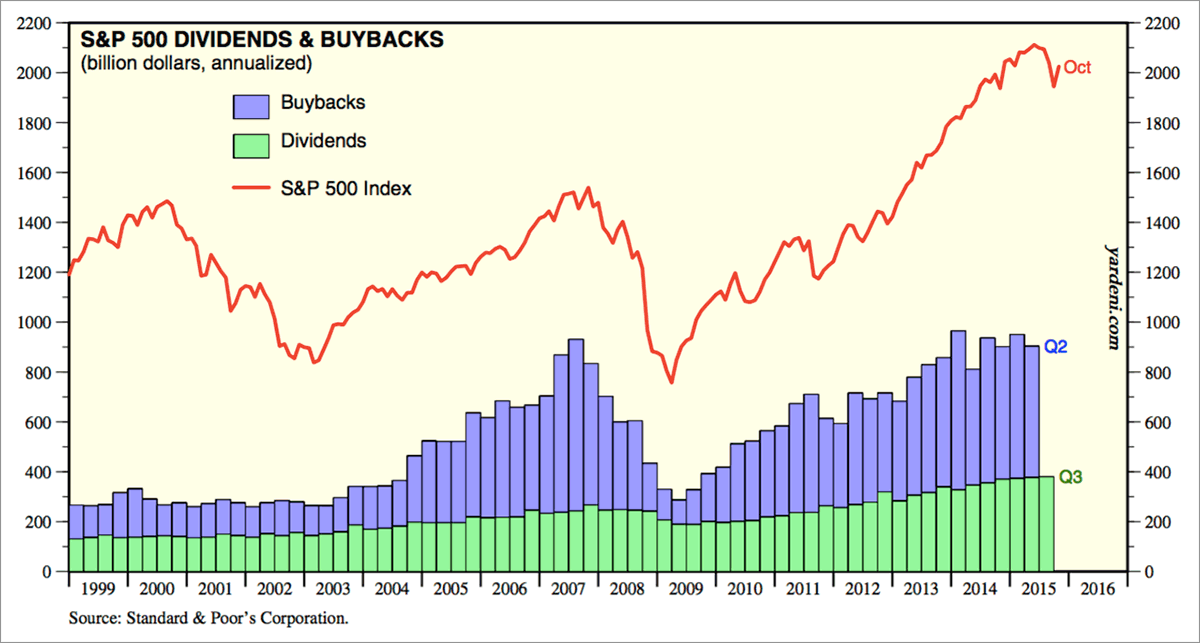

It's true that buybacks represent a large amount of money. In the past 12 months, companies have spent $555b on buybacks. Over the past 3 years, over $1.5t has been spent on buybacks. This is a lot of money (data below and elsewhere in this post from Yardeni).

It's also true that buybacks represent a large source of demand for equities, larger than the demand from equity mutual funds and ETFs. The data below is gross buybacks, not net buybacks, an important distinction we'll discuss below (data from FT).

These huge sums represent stock buying demand in excess of that from institutions and individuals. There is little doubt the stock indices have moved higher with the help of the money being spent on buybacks. This is not new: it was also a pattern in the previous bull market.

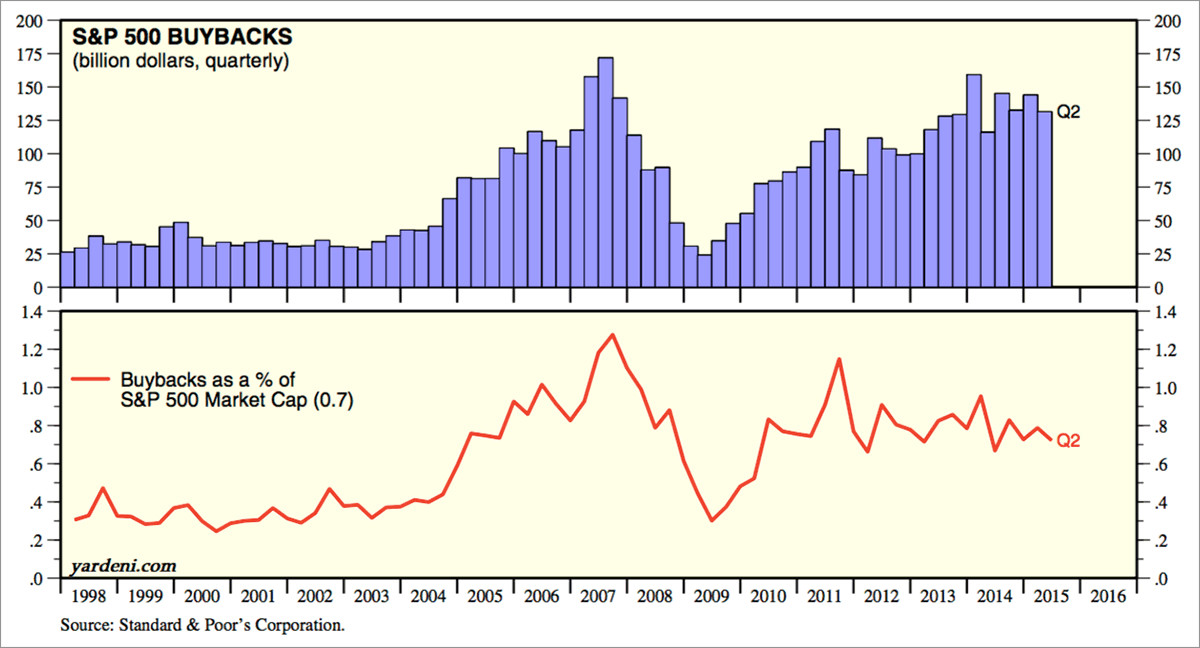

While the dollar amounts of buybacks are large, it is small relative to the size of the stock market. In the 2Q, gross buybacks were less than 1% of market capitalization. Buybacks are big; the stock market is really, really big.

What is often ignored when buybacks are discussed is that companies are also issuing shares. Most prominently, executives are often given compensation in the form of share options; buybacks have become a way for the company to mop up the resultant increase in shares. So, gross buybacks might be 0b but the net was closer to 0b. You can take the gross buyback amounts in the charts above and cut them in half to get a more accurate view of the affect of buybacks.

(Side note: other corporate finance activities, like M&A, also affect company share count. For simplicity, we're using buybacks as an umbrella phrase).

As you can see in the chart above, net buybacks were much bigger in 2007 than they are today. Also, buybacks have become less important over the past year and a half, during which the S&P has gained more than 20%. Buybacks urged in mid-2011 as the stock market fell. Buybacks are important, but they aren't the only thing driving the stock market, up or down (data below and elsewhere in this post from FactSet).

If all that mattered was buybacks, then those stocks with the most buybacks would consistently outperform the market. They don't. The red line is comprised of all the stocks with a net reduction in shares outstanding of 5% or more in the trailing 12 months. They have underperformed both the S&P (blue line) and the Nasdaq 100 (green line) during the past two years.

Only 4 of the stocks with the top 10 largest buyback programs beat the index in the past year (green shading); 5 stocks actually declined. Share price performance is about much more than 'financial engineering'.

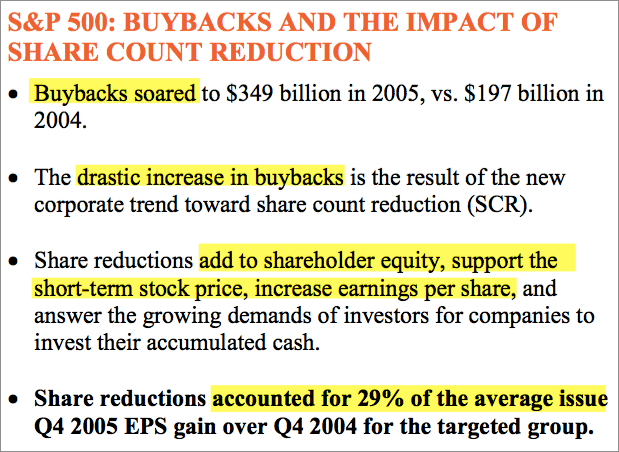

Buybacks are not the result of the Fed's zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) or quantitive easing policy (QE). Buybacks became prevalent more than 10 years ago. They were more significant as a proportion of the stock market in 2005-07 than they have been during most of the past 3 years. The trend towards buybacks was underway well before 2008 when ZIRP and QE entered the investment community vernacular.

Buybacks were often discussed and widely disliked 10 years ago. Skeptics used the same arguments then that are also used today. None of this is new. The excerpt below is from 2005.

The affect of share reduction on EPS was significant 10 years ago, as share count declined almost 10%. That hasn't been the case in the past several years, with the share count back unchanged since the end of 2009.

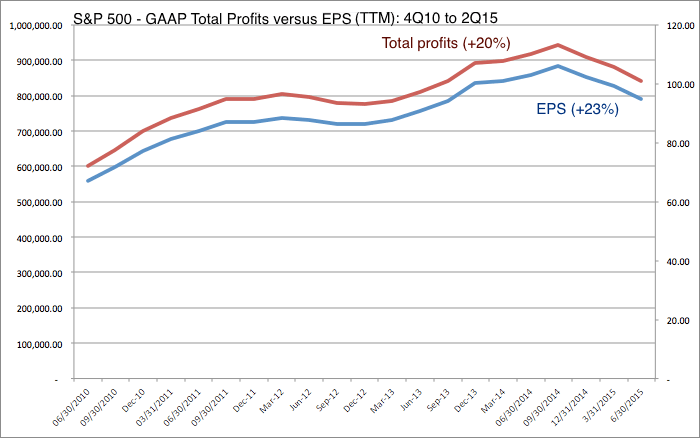

This brings up the biggest myth about buybacks: that they are responsible for most or all of the recent growth in corporate earnings per share (EPS).

Between 4Q 2010 and 2Q 2015, annualized EPS for the S&P rose 23%; profits rose 20%. In other words, higher profits accounted for nearly 90% of the growth in EPS; the remaining 10% was the affect of the reduction in share count (data from S&P).

Why is there so little difference between profits and EPS growth? The effect on shares outstanding of net buybacks has been minor: a reduction of about 2% since 2010 (TTM basis). That shouldn't be surprising: remember, the dollar amounts spent are small relative to market capitalization and almost half of the buybacks are offset with issuance.

You didn't need this data to reach the same conclusion; logic would have also told you that profits are primarily driving higher EPS. Employment growth is now the best since the 1990s; compensation growth is the highest in 6 years; consumption growth is the highest in 8 years. Why would anyone expect there to be no sales growth under these conditions?

Moreover, there has been a surge in profit margins to all-time highs. The combination of sales growth and an expansion in margins can only lead to higher profits (data from BBG).

Finally, buybacks are said to come at the expense of investments in growth that would be a better use of capital. There are several problems with this argument.

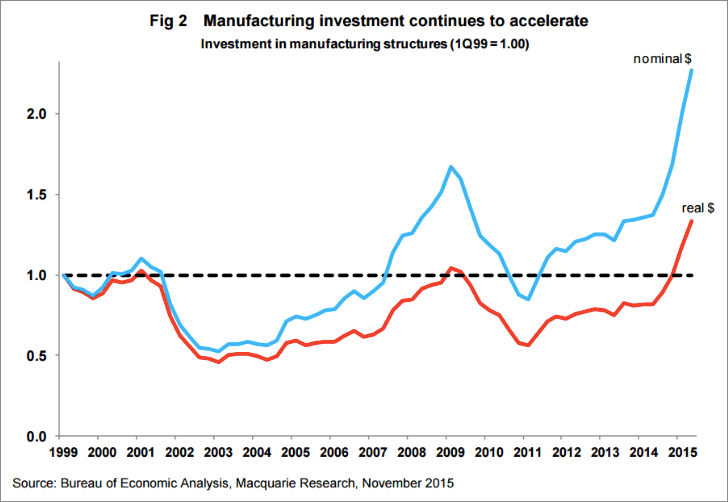

First, investment in manufacturing is in fact booming (data from BEA).

Second, the annual growth in R&D investment is 8%, matching the levels from expansions in the 1990s and 2000s.

It's hard to say companies are not investing in future growth. Should they be investing even more? Probably not.

Capacity utilization rates are below optimal. Were they higher, then greater investment would be warranted, but that's not the case at present. There is no shareholder benefit to over-investment.

Some of the recent reduction in capital spending is associated with the energy sector, which accounted for 39% of global capex in 2014 (article). This sector is certainly not in need of greater investment.

Which brings up a key point: the companies that are generating the most cash and engaging in the most buybacks are in industries that are less capital intensive, like technology. So there might well be a mismatch between companies accounting for most of the buybacks and those most in need of investment in their operations.

More generally, there is a good argument to be made that the rise in corporate buyback activity since the early 2000s has much to do with the continued shift in the economy away from lower profitability and more capital intensive industries to those like technology and healthcare that require less capital and generate high amounts of cash.

In summary, it's true that buybacks represent a large source of demand for equities and have helped push asset prices higher. But much of what else is believed about buybacks is a myth.

Interview with Urban Carmel on Market and Economic Outlook: