When Jim Chanos called China Dubai times 1000 in 2010 many chuckled. Now that opinion has slowly become the consensus or at least a matter of serious debate. What is perhaps most interesting about Nomura’s September 14 report, “China: Solving the debt problem,” is the fact the solutions involve a China default. It is rare – if not a historic first – for a major bank to say the world’s second-largest economy is likely to default on its debt.

With total debt-to-GDP at 309%, something is likely to give

Discussing government and corporate debt peril in public forums is typically muted if not outright censored. Although hedge funds have addressed the China default debt topic, for a major establishment-bound bank to actually discuss the grotesque details and predict a default in a major economy is something unusual.

But that’s just what Nomura’s research team, led by Yang Zhao, did.

Nomura estimates China’s total debt – government and corporate – is RMB211.8 trillion or 309% of GDP. The vast majority of this debt is corporate, which from a leverage perspective looks better. The non-financial sector accounted for RMB158.5trn (231% of GDP, up by 92pp from 2007) and the financial sector for RMB53.3trn (78% of GDP, up by 49pp).

Don't miss Richard Duncan: China Slamming Into a Brick Wall

The debt is up nearly 141% since 2007, which leads Nomura to conclude “a rising default rate is inevitable.”

“There is essentially only one practical way to reduce the stock of outstanding debts: defaults,” the report concluded. “As the debt-to-GDP ratio reaches a tipping point, it becomes harder for borrowers to meet the interest payments on their debt. A high debt-to-GDP ratio makes the economy more vulnerable to volatility in asset prices…”

Unrealistic to either inflate or “grow” its way out of debt

The almost reflexive response to debt is that an economy can either grow its way out of debt or inflate its way out of debt, thus avoiding default.

At the most basic level there are two ways to lower a debt-to-GDP ratio – either reduce the numerator, which means lowering the growth of debt to below GDP growth, or increase the denominator, which means promoting GDP growth to above the growth of debt. However, raising the denominator is only a theoretical option because in practice there is no sustainable way to boost GDP growth to a pace that outstrips the immensely fast pace of debt growth.

Nomura says in China’s case, these two options are not feasible.

Unless the financial system and economic structure are fundamentally reformed – which we believe is a goal beyond a practical macroeconomic discussion for the next five to 10 years – “growing out of debt” is not an option. The math is simple: To contain or even reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio, we need the gap between debt growth and nominal GDP growth to shrink, or better still, turn negative. However, reducing the gap requires disinflationary, or even deflationary, pressures that are not favorable for GDP growth, hence lowering the ratio has to be premised on the acceptance of a slower rate of GDP growth (Figure 22). In other words, policymakers need to accept a lower GDP growth rate if they are serious about wanting to reduce the debt ratio, otherwise they have to concede that the debt ratio will continue to rise.

With growing out of debt unrealistic, there is also inflating out of the problem. That, too, is fraught with peril, the report noted:

Inflating the economy out of the debt problem, by lowering the debt-to-GDP ratio via a high enough level of inflation so that nominal GDP growth outpaces debt growth is, in our opinion, just as unlikely to succeed. And the reason why is similar: The only way to generate inflation is to print more money than needed, which would lead debt to outgrow the general price level. To generate a quick spike in inflation, policymakers would need to create sufficiently rapid M2 growth, which in turn requires rapid loan and/or debt growth. Currently, M2 growth is around 12% and loan growth is around 14%, both exceeding nominal GDP growth by some margin – yet inflation remains low. Put simply, there is no practical way to increase the denominator sharply without increasing the numerator even faster.

One must be careful with default, because after it occurs few are typically winners. Nomura notes that it will likely be the State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) that will be allowed to partake in the default party more so than private corporate enterprises:

A large-scale debt default would mean a debt crisis, likely then leading to a financial crisis, which is obviously not a policy option. An orderly default process will involve delicate policy management. In the end, the debt default ratio in terms of the outstanding volume of debt must rise – NPLs and bond default rates must be much higher than their current levels. Only a very privileged few will be able to default on their debt and survive, and we believe it is far more likely that those survivors would be SOEs rather than private companies. We expect to see more defaults from the SOEs than the private sector, as well as some creative ways – with debt-to-equity swaps being just one example – to manage the unwind.

What this all means is that interest rates are likely to head near zero — the place at which such defaults can find their most advantageous environments. And of course, when interest rates fall, so, too, does the currency value. In the end, it is likely to become one big mess that might have global implications.

See Bert Dohmen: China Still the Greatest Threat to Global Markets

Nomura is far from alone – besides for many others including hedge funds warning about Chinese debt load. The BIS’ latest report is sounding the alarm (full PDF from BIS here). Below is a brief quote:

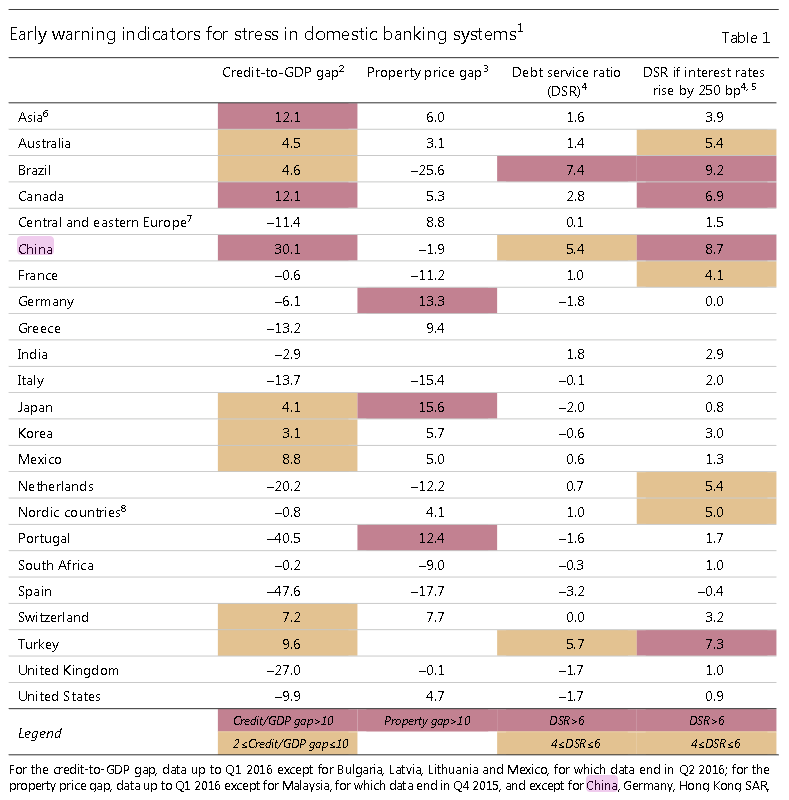

Estimated debt service ratios, which attempt to capture principal and interest payments relative to income, appear to be at manageable levels at current interest rates for most countries, although they point to potential concerns in Brazil, Canada, China and Turkey (third and fourth columns).

And:

Cross-border bank credit to emerging market economies declined by billion during the first quarter of 2016. This latest fall pushed the total outstanding down to .2 trillion, while further accelerating the annual pace of decline to –9%. As in the preceding two quarters, diminishing claims on China drove the aggregate quarterly change in lending to EMEs (and to emerging Asia in particular). The billion drop in cross-border bank credit to residents of China was smaller than those seen during previous quarters, but it still took the annual growth rate down to –27% (Graph 4, bottom panels). The outstanding total came to 8 billion as of end-March 2016. Since hitting its all-time high at end-September 2014, cross-border bank credit to China had contracted by a cumulative 7 billion (–33%) by end-March 2016, with interbank and inter-office activity leading the decline.

As Ambrose Evans-Pritchard of The Telegraph notes:

China has failed to curb excesses in its credit system and faces mounting risks of a full-blown banking crisis, according to early warning indicators released by the world’s top financial watchdog.

A key gauge of credit vulnerability is now three times over the danger threshold and has continued to deteriorate, despite pledges by Chinese premier Li Keqiang to wean the economy off debt-driven growth before it is too late.

The Bank for International Settlements warned in its quarterly report that China’s “credit to GDP gap” has reached 30.1, the highest to date and in a different league altogether from any other major country tracked by the institution. It is also significantly higher than the scores in East Asia’s speculative boom on 1997 or in the US subprime bubble before the Lehman crisis.

By Mark Melin

Related podcast interview:

Book Interview With Worth Wray: A Great Leap Forward?