Originally posted at ExecSpec.net

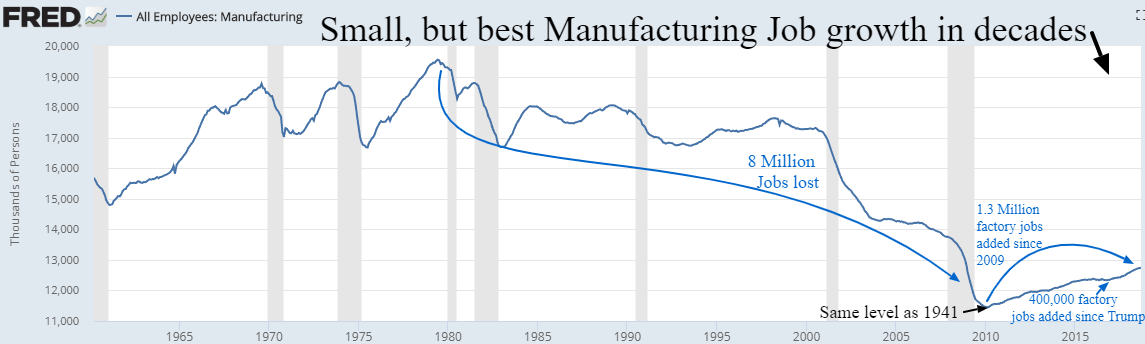

Trump’s claim of bringing back American manufacturing jobs is boastful but does have some truth. Since the manufacturing halcyon days of the 1970s, the US dollar was allowed to depreciate and cheap labor abroad sent US factory jobs into a multi-decade tailspin. Manufacturing output rose, but 8 million jobs were lost. In his first 20 months, Trump has added about 400,000 factory jobs with record unmet demand for more workers in a strong capacity starved growth phase since he was elected.

In measuring the factory employment growth rate, we are witnessing the fastest employment rate since 1984. More impressive is that employment growth always slows toward the end of an economic cycle, yet this time after 9 years we see acceleration. With record low jobless claims, the current worker additions in manufacturing and throughout this economy are impressive. With virtually full employment, we rely on new young adults entering the labor pool along with converting those not seeking work to return from the sidelines.

It is possible to speculate that there would be a significant boost to the current above normal GDP growth rate if we could fill a few million of the almost 7 million unfilled job openings (see below). With Boomers retiring in record numbers for years to come, it’s unlikely these openings will shrink much until the economy contracts. The avenues for increasing employment are challenging, yet obvious: more skilled immigration, job training, and automation.

It’s not just the US in need of more labor. The Western world needs help shrinking the large worker deficit. Germany’s Merkel has already compromised in limiting illegal immigrants, but has smartly pivoted to pushing for skilled German speaking immigrants from around the world to ameliorate the record job openings. German companies are moving abroad to locate factories where more skilled labor exists – a great opportunity for aggressive countries to hold out a neon welcome sign.

Even in the closed society of Japan, the worker shortage is acute. Immigration for Japan would be a novel idea and those countries that work hardest at inviting skilled labor will be able to gain a share of global output. Japanese demographics and a highly protected society create one of the greater challenges among aging rich nations.

Needing more workers is a better problem than the alternative, but most leaders focus on creating demand, when supply is the current long-term dilemma. As Trump’s trade war encourages rerouting supply chains away from China and elevating domestic production, leaders need to understand the win-win solutions of a more hospitable immigration policy and investment in automation with policies protecting the social fabric. Unfortunately, balanced productive economic and social policies seem unlikely in this hyper partisan world.