Originally posted at ExecSpec.net

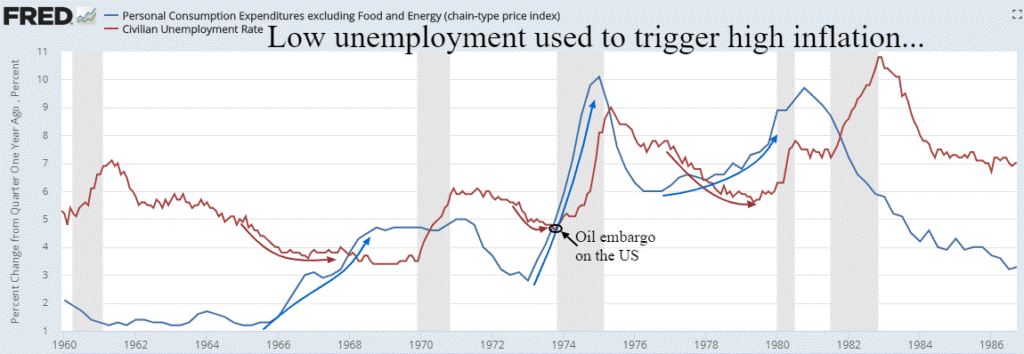

Milton Friedman promulgated the Phillips Curve interpretation that posits a tight labor market generates higher inflation. Since 1967 this has been the primary tool of central banks and economists in forecasting inflation. During the previous generation it appeared that falling unemployment during an economic recovery would always trigger a strong inflation response.

Today’s near record low unemployment should support a robust economic expansion but has confounded economists expecting worrisome inflation.

The inflation to unemployment sensitivity was strong in the 1960s and 1970s as boomers entered the workforce triggering abnormal rates of spending and inflation. Combined with the Vietnam War and Johnson’s 1964 War on Poverty, this inflationary baby boom phase caused the U.S. to close the gold window in 1973 and send the world to free floating currencies. Pent up pricing pressures devalued the US dollar and prompted the infamous Middle East oil embargo causing a vicious phase of stagflation until Paul Volker took charge of monetary policy in 1979.

Since Volker’s tight monetary policy of the 1980s, the unemployment to inflation correlation has been far less acute. The record surge in job seekers in the 1970s has been replaced by the record surge in job openings today which historically would trigger rapid wage inflation. Wages are accelerating at a modest 2.9 percent clip, but higher wages will not attract workers that don’t exist.

Record unfilled job openings have boosted job confidence (quit rate) to 17 year highs, as more workers are willing to quit their job for a better offer. With a very strong GDP and workers trading up for better paychecks, inflation is edging higher.

Interest rates are rising as expected, not because of inflation fears, but to provide the Fed with ammunition to ease credit when the next recession becomes evident.

The inflation metric using core Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) by Fed Chairman Jerome Powell may move above target temporarily to the 2.2 to 2.5 percent range as wages, tariffs, and a record labor shortage briefly move prices higher. However, we concur with the Fed that core PCE inflation will remain subdued longer term. Until we see the global economy accelerating in sync along with emerging markets and higher commodity prices, we would not be too concerned about an inflation induced credit tightening contraction.

As in the 1990s when inflation remained low throughout the long expansion, we will be watching credit spreads, delinquency rates, and banking surveys to provide clues for the end of this record economic expansion cycle. The metrics we watch are in excellent shape today and indications are that historical relationships of unemployment and inflation as well as inverted yield curves are less important to the economy than in past decades.