I was reading through some J.P. Morgan research over the weekend, and came across a number of key charts that I thought I would share with you today. But first, let’s take another look at the stark contrast between U.S. and international stock performance that has developed this year.

While the U.S. economy and markets continue to chug along just fine, the rest of the world is having trouble keeping up. Like a bull market riding on narrow leadership, when only a handful of countries’ stock markets are moving higher, it can be a sign of problems ahead.

I don’t believe the situation is dire just yet, but it’s important to recognize that significant wealth has been destroyed this year in many areas of the world. Should this continue, it’s not difficult to imagine some spillover into U.S. markets.

Furthermore, even those who don’t believe in the wealth effect have to acknowledge that the value of companies’ and governments’ balance sheets does have an impact on spending and investment decisions. There is a subtle feedback loop in place between markets and their underlying economies.

The good part (from the U.S.’s standpoint) is that due to our high reliance on domestic consumption, our economy is somewhat insulated from gyrations abroad. Not only that, our stock market has already de-risked in a way that could mute future downside potential.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the multiple investors are willing to place on future earnings. In the chart below, courtesy of J.P. Morgan, we can see the large correction that occurred with regard to valuations this year. After reaching a forward P/E of nearly 19 in January, that multiple has fallen by roughly two handles to below 17 (data is as of the end of Q2).

So while the price correction that we experienced this year has largely resolved itself (the vast majority of major averages are back to where they were), it has created a lasting effect on overall valuation levels. During the last eight months, stocks have treaded water while the economy and corporate profits have grown considerably.

One interesting way to look at the effects of this is through the lens of earnings yield. Recall that the earnings yield is the inverse of the PE ratio, and tells us the percentage a company (or group of companies) earns on each dollar invested in the stock.

With a PE of 19, that earnings yield is 5.26%. At a PE of 17, the earnings yield rises to 5.88%. This means that stock investors are getting a bit more of that earnings stream ( ~11%) when they buy a share of stock now, as opposed to the beginning the year.

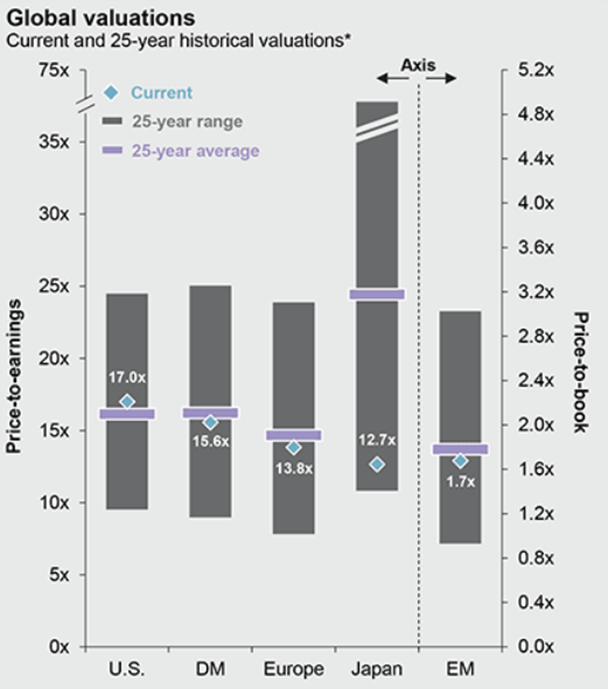

While I’m generally not a big fan of historical comparisons (because they often forgo important considerations such as what the cost of money was back then vs. today), you may find the following chart a bit calming (all charts with a gray background are courtesy of J.P. Morgan).

On the left side of this chart we can see that the current PE is just a smidge (technical term) higher than its 25-year average. In other words, even at today’s near-record prices, stocks are trading at roughly the same valuation levels they have over the past two and a half decades.

That may not make you want to go out and buy stocks hand over fist, but I do think it forces you to question some of the claims being made about this market being outrageously expensive and overvalued. It’s also worth noting that across the rest of the world, stock valuations remain near the middle of their 25-year range.

Moving on, we know that valuations have no role as a market timing indicator, but they do influence future long-term returns. It’s important to understand this concept because it will help to govern and control your expectations moving forward. If you know, for example, that returns moving forward are likely to be lower than average, you may be less inclined to load up on risk.

We can see the relationship between PEs and subsequent returns in the chart below. The yellow line is a simple regression line, or line of best fit. Now that market’s PE has come back down to earth, expected future returns have bumped up a bit.

But of course this chart assumes that you’re buying and holding those shares, which there is a good chance we will NOT be doing here at DTL. Even though the economy is performing well now, we know that the economy moves in cycles, and that we are likely in the latter innings of this expansion. That’s why we place so much emphasis on price action and other leading economic indicators that will give us a leg up when the next inflection point is upon us.

Switching gears, this next chart shows us the relationship between earnings growth and capital expenditures (capex), and provides some basis for optimism. In this chart, the gray line represents S&P 500 earnings per share (left axis) and the green line shows capex with a one year lag.

The fact that the two follow each other quite closely suggests that the current earnings boom we’re seeing should be followed by a continued rise in business investment over the next few quarters. That should help to bolster the above-trend (my opinion) GDP growth that we’ve seen lately, and could help to keep our markets humming.

Next, I’ve heard some fuss lately about expanding debt levels at the corporate level, and while that’s certainly the case, it appears that companies’ ability to service that debt remains adequate. The chart below shows the S&P 500 coverage ratio, which is calculated by dividing a firm’s EBIT (Earnings before Interest and Taxes) by its interest expense. The higher the number, the more easily the firm (or group of companies) can manage their current debt loads.

While the S&P 500 interest coverage ratio has come down from where it was between 2012-2015, it remains at a healthy level and has been creeping higher since the beginning of 2017.

Finally, switching gears once more, this next chart shows the interest rate differential between our 10-year Treasury note and other 10-year government bonds around the world. Notice that this differential is at the highest level in decades.

To me, this signals two things: upward pressure on the dollar, and downward pressure on long-term interest rates. The upward pressure on the dollar comes from foreign investors demanding dollars to invest in U.S. bonds and other assets, and the downward pressure on yields comes from those same investors buying Treasury bonds to get more (safe) yield than they can in their respective countries.

While a stronger dollar is not necessarily great for the economy, it often applies downward pressure to commodity prices and inflation in general. And lower inflation would help to keep long-term yields in check. So … that’s a long way of saying that I believe long-term yields will continue to remain anchored here in the U.S., and that should help to promote continued gains in both the economy and stock market.

Okay, one last chart just because I can’t help myself. September has been the worst month in history for the S&P 500, but as we all know, the fourth quarter, which is just ahead, is usually a good one for equity prices.

Could we perhaps be given an early Christmas gift in the form of reduced trade tensions? Probably not, but just think what that could do if it did happen. We’re entering a seasonally strong period of the year with modest valuation levels and a strong economy. If you add in a tailwind from reduced trade friction, we could be in for a strong few months.

The preceding content was an excerpt from Dow Theory Letters. To receive their daily updates and research, click here to subscribe. Matt is also the Chief Investment Strategist at Model Investing. For more information about algorithmic based portfolio management, click here.