“[I]f the game of order-versus-chance is to continue as a game, order must not win. As prediction and control increase, so, in proportion, the game ceases to be worth the candle. We look for a new game with an uncertain result.” —Alan Watts

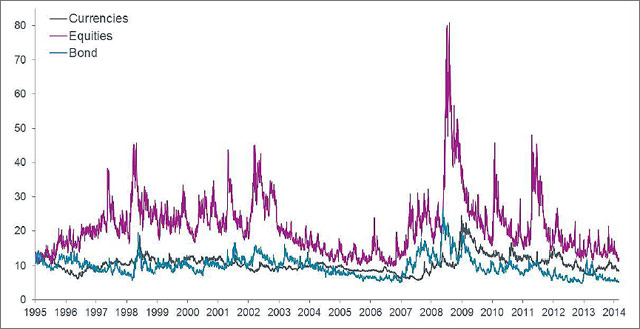

Accompanying the relentless rise in risk asset prices is the decreasing value for protection against their fall, as exhibited in the low option premiums highlighted in the chart below. Observers wonder whether it reflects complacency around market stability. Some (FT.com subscription required) suspect that central bank policies have contributed to this attitude.

The Implied Volatility of Assets Is Low

Source: Bloomberg

Admittedly, those policies have been unconventional to say the least, with the ECB recently moving from a zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) to a negative interest rate policy (NIRP).[1] As if admitting guilt, John Williams and William Dudley, the respective presidents of the San Francisco and New York Feds, recently expressed their worries about the potential risks of monetary policies to financial stability, albeit from different angles. Specifically, Williams criticizes the standard macro models used in economics. He advocates a revision of asset price modelling by relaxing “the assumption of rational expectations and allow people’s decisions to be driven by their perceptions of what the future may hold, whether grounded in reality or not”, adding that a “growing body of evidence in behavioral economics and finance shows that people’s expectations of future asset returns depend on their past experiences” (emphasis mine).

As I have explained in previous articles, I am in favor of such a shift in thinking and advocate more broadly, for example, a rebalance between the various sciences that can provide investment insights with more weight on biology and the humanities. However, I also must point to its inevitable destination, as well as highlight the main obstacle along the path that leads us there. In fact, making experiences inclusive in our research is the proverbial opening of a can of worms for those who can’t handle (the truth of) such slippery creatures. For starters, what do we mean by experiences? Are these only referring to the thoughts that led to the investment decisions, regardless whether they were rational or not? Do they include the memories that color those decisions? What about emotions? And if such experiences are ultimately “captured” in prices, what does this say about their discovery?

[Read: Jeffrey D Saut: Volatility?!]

Among the most significant implications of this shift is the change from a machine to a mind-body perspective on the economy in general and markets in particular. Specifically, we can translate individual mentality into the collective setting by formalizing the market’s mind, a term investors already casually refer to, often in the context of Benjamin Graham’s ‘Mr. Market’. In turn, it leads to what I have called the market’s version of the mind-body problem, which can be stated as a question: what role do inter-subjective sensations like exuberance or despair play in market states? In other words, why are market processes like calculations, transactions, and flows accompanied by such collectively shared feelings? Coming back to Williams’ criticism, we know one thing: leaving them out somehow fails to convey how markets feel to those who participate (and ultimately make the decisions). More broadly, this problem refers to the difficulty in understanding, let alone explaining, the dynamics between the physical ‘real’ economy and the psychic capital markets, e.g. the discrepancies between fundamental reality and the one imagined by the market. When the market makes up its mind, it not only employs cognitive expressions like signals from quantitative models and consensus expectations. The market is also infused by a mood which completes, as an overlay, its mental state. Specifically, it is the market’s mood that embeds and conveys investor experiences in the phenomenal sense. Let’s take the collapse of Lehman as an, admittedly extreme, example of financial instability. Previously, I expressed it as follows:

“Lehman was a reality check. We experienced a near fatal market stroke and escaped it more by luck than wisdom. Crucially, it didn’t feel like a machine breaking down at all. Instead, what came over us was the shared sensation of paralysis which accompanied the market seizing up. It was this overwhelming experience that impresses how it is like to collectively be in such an existential market state as humans.”

Traditional approaches, in particular those assuming equilibrium, fail to address this problem, exactly because they start from a machine perspective. They also cause much confusion around topics like the nature of money, the role of debt, and the discovery of prices. Instead, the mind-body perspective recognizes the fact that psycho-physical bridging takes place in our economic system and that price discovery plays a delicate, and often painful, role in that respect. Specifically, prices form the symbolic numerical building blocks with which we bridge the physical economy (e.g. of products) with our psychic one (e.g. of wants) and create ‘value’. Crucially, in a very concentrated format prices contain, indeed, all of our experiences that Williams refers to, not just the rational information content. Obviously this puts a different light on interest rate policies.

In the context of central banks we can interpret psycho-physical bridging in terms of their famous transition ‘mechanisms’. In Europe, for example, these are not working properly with animal spirits clearly muted. Unfortunately central bankers do not recognize that the problems start with the term ‘mechanism’ which incorrectly suggests we are dealing with a process that can be functionalized and controlled. Moreover, once we accept the mind-body perspective it becomes clear that they have taken one-sided measures to (quantitatively) ease the pain of uncertainty, taking it out of the equation of experiences. The problem is that moral hazard and other (unintended) consequences of these policies may not always be apparent on the cognitive surface which we explore with our analytical methods. In general, interference leads to the unhealthy over-reliance on such analysis: “The more one interferes, the more one must analyse an ever-growing volume of detailed information about the results of interference on a world whose infinite details are inextricably interwoven” (Watts, 1966).

A number of researchers (most recently Nassim Taleb with his anti-fragility thesis) have pointed out that repressing naturally occurring behavior, for example because it is unpleasant, will exactly cause it to build up, sometimes elsewhere in the system. Jung argued that this occurs in the unconscious domain as far as repressed emotions are concerned. On that note, the link between emotions and volatility is easily made (e.g. Howard, 2014). Hedge fund legend Kyle Bass’s observation that “if you suppress volatility long enough, then when the 'event' happens it is greater than the sum total of all the suppressed vol over time" is echoing Jung:

“[I]f it is repressed and isolated from consciousness, it never gets corrected and is liable to burst forth suddenly in a moment of unawareness. At all events, it forms an unconscious snag, thwarting our most well-meant intentions. (CW 11, par 131).”

To conclude, if anything, the mind-body perspective highlights the similarities between minds and markets. Both are complex adaptive systems where forces compete and cooperate to coordinate behavior. For the mind, on one side we have the subliminal forces of emotions and intuition, whereas on the other we have the cognitive ones of logic and rationality. In investment research we use analysis to support the latter.[2] However, what the market’s mind-body problem highlights first and foremost is the lack of a systematic approach to support the qualitative, often subliminal, forces with which we engage the collective market mind. This could help to balance our over-reliance on quantitative methods of research and policy, exactly in order to better understand the more elusive properties of the inter-subjective ‘experiences’ that complete market states for investors and inform their decisions. We need to see this in the context of the flawed consensus within behavioral finance that emotions, and the heuristics they trigger, are bad. Among the insights from consciousness research is the realization that a healthy mind is a balanced mind, allowing both emotions and rational thoughts to compete for its attention. It also requires a certain level of freedom to make discoveries which, among other things, also allows for surprises. In the words of the Spanish philosopher Jose Ortega y Gasset “To be surprised, to wonder, is to begin to understand.” Clearly these are crucial issues for our debate.

[Listen to: Tracie McMillion: Investors Beware Complacency – Low Volatility Does Not Mean Low Risk]

Finally, as far as discrepancies between the ‘real’ economic cycle and the imagined speculative one are concerned, volatility in macroeconomic surprises in the U.S., for example, is not confirming the recent lows in those of financial assets and has recently picked up (see chart below). Perhaps it is showing that not everything is as smooth as implied under the financial stability scenario of central bankers? Or in the words of Jung, “Through pride we are ever deceiving ourselves. But deep down below the surface of the average conscience a still, small voice says to us, something is out of tune — There is no coming to consciousness without pain.”

Volatility of U.S. Macroeconomic Surprises Has Picked Up

Source: Bloomberg

This document is not intended for retail distribution and is directed only at investment professionals. It should not be distributed to, or relied upon by, private investors. The information in this document is based on our understanding of the current and historical positions of the markets. The views expressed should not be interpreted as recommendations or advice. Past performance is not a guide to future performance. The value of investments and the income from them may go down as well as up and is not guaranteed. This document is accurate at the time of writing but can be subject to change without notification.

Kames Capital is an Aegon Asset Management company and includes Kames Capital plc (Company Number SC113505) and Kames Capital Management Limited (Company Number SC212159). Both are registered in Scotland and have their registered office at Kames House, 3 Lochside Crescent, Edinburgh, EH12 9SA. Kames Capital plc is authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA reference no: 144267). Kames Capital plc provides segregated and retail funds and is the Authorized Corporate Director of Kames Capital ICVC, an Open Ended Investment Company. Kames Capital Management Limited provides investment management services to Aegon, which provides pooled funds, life and pension contracts. Kames Capital Management Limited is an appointed representative of Scottish Equitable plc (Company Number SC144517), an Aegon company, whose registered office is 1 Lochside Crescent, Edinburgh Park, Edinburgh, EH12 9SE (PRA/FCA reference no: 165548).

Footnotes

[1] Zero, respectively Negative Interest Rate Policy.

[2] For example, one of my main models attempts to signal shifts in the market’s emotional state by analyzing various measures of volatility.