Last week’s market moves triggered by angst over the decision by Chinese authorities to depreciate their currency have been painted by some as a disaster for the US. The focus is typically on those firms doing business with or in China that have been hurt by China’s recent downturn and by the depreciation in its currency. Add to that the speculation concerning the negative consequences for the US real economy and the likelihood that the recent developments might derail the Fed’s expected rate move back towards a more normal policy stance. Interestingly, this past week both Atlanta Fed President Lockhart and New York Fed President Dudley suggested that the problems in China were unlikely to be a major factor, barring other incoming data, to cause the FOMC to postpone a possible September rate move.

Do markets know something the policy makers don’t, or are markets focusing too much on individual firms with ties to China and not looking at the bigger picture and how those firms fit into the broader economy? We think the problem is the latter, when it comes to policy, and will attempt to elucidate why that is so. Putting aside the recent financial market turmoil, there are reasons to believe that neither the problems in China nor the appreciation of the dollar will have serious implications for real economic activity in the US. To see why we need to consider both the export and import situation of the US.

[Read: Global Deflation Trends to Intensify?]

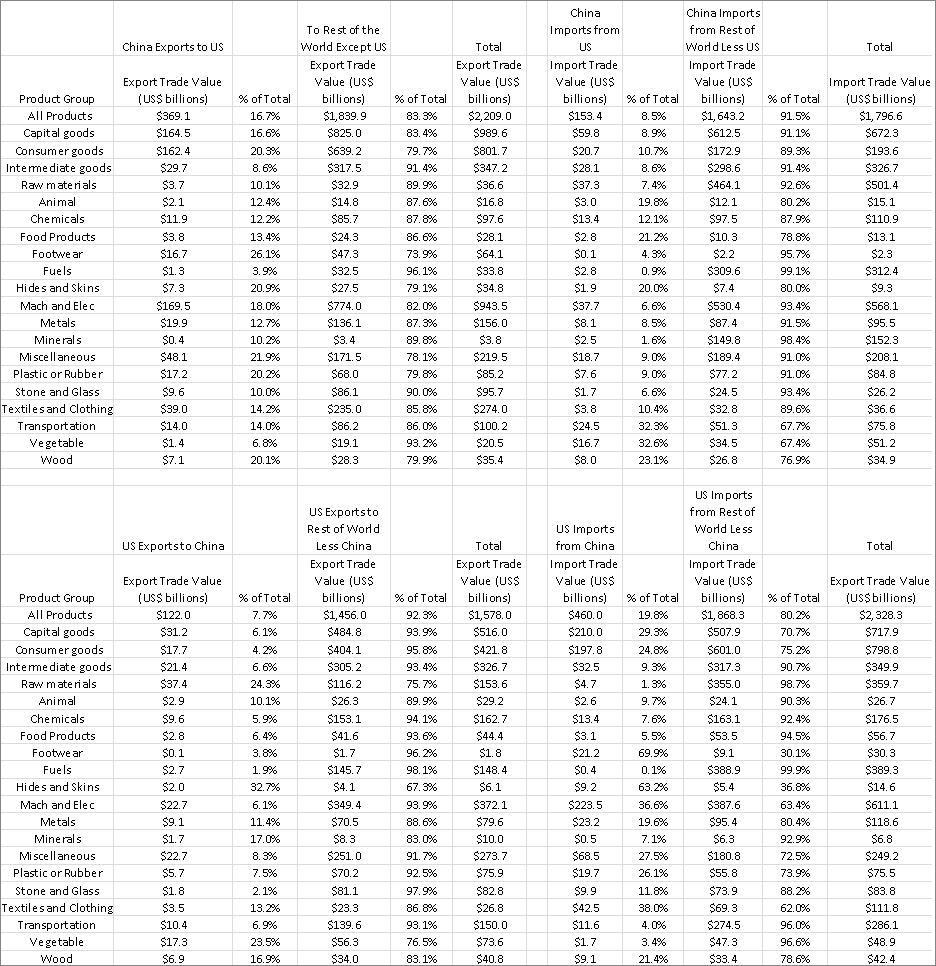

The table below details World Bank import/export data as of the most recently available date (2013) for both the US and China (note that because of data differences, exports from the US do not necessarily match one for one with China’s imports from the US). The US imports about $460 billion of goods from China; 29% of that total is capital goods and 23% is consumer products. To put those numbers in perspective, overall we import about 98% of the clothing purchased in the US from all import sources, of which about 34% is from China. However, total spending in the US on clothing only amounts to about 3.5% of consumer expenditures. The depreciation of the yuan is a price cut on these imported products, which benefits both consumers and users of capital goods. In total, however, our China imports accounted for only 3% of nominal GDP in 2013. So, realistically, U.S consumers and businesses experienced about a 3% drop in the price of what amounts to a very small proportion of GDP.

China’s other trade partners, which are huge suppliers of raw materials, capital goods, and intermediate goods to China, will bear the brunt of the change in the value of the yuan. It seems unreasonable, given the importance of China’s export sector, to expect that the Chinese will cut back on imports. This is because those imports are critical inputs in many cases to the goods that China exports, since China’s trade is based upon relatively low-value-added products. So China will pay more for its inputs and will likely have to absorb the cost difference internally.

For the same reason, it is also unlikely that our exports to China will lessen significantly just because of the change in the exchange rate. The table shows that we export only about $122–$150 billion to China, out of $1.6 trillion in terms of total US exports. Put another way, our exports to China are less than 8% of our total trade with the world, and in 2013 we had a trade deficit overall of approximately 6% of GDP. Our major exports are in the form of capital goods, consumer products, intermediate goods, and raw materials. Again, none of these export categories represent large components of total US GDP.

To put the trade picture in perspective, while the situation in China and depreciation of its currency are important, on balance they benefit more segments of the US real economy than they hurt. The distributional effects across the rest of the world will be different, hurting some and benefiting others. But we suggest that the main effect, given the composition of China’s trade, will be a narrowing of margins on Chinese goods, with little net impact upon the world or US economies. It is these considerations that are likely behind the recent Fed policy makers’ suggestions that September is still a viable time to consider a rate move.

Related: