During times of uncertainty, such as the prelude to the Brexit vote, investors tend to gravitate toward the Japanese yen. This causes the yen to appreciate and has led to the common perception of the yen as a safe-haven currency.

This strengthening of the Japanese currency during periods of risk aversion has become so repetitive and ingrained that it is rarely questioned. But why is it that global investors flock to the currency of the world’s most indebted nation whenever trouble arises?

The yen’s role as a safe-haven currency has been well documented. Aside from the many white papers and research studies demonstrating that conclusion, a quick review of recent events shows this to be the case.

During the financial crisis and its aftermath, the yen appreciated by more than 20 percent. Later, in 2010, worries about peripheral European debt led to a 10 percent appreciation against the euro. A similar phenomenon occurred again in 2013 when uncertainty around Italian elections caused the yen to rise over 5% against the euro and 4% against the dollar … in a single day.

Even when Japan was leveled by the Great East Japan earthquake in 2011, the currency somehow managed to rise.

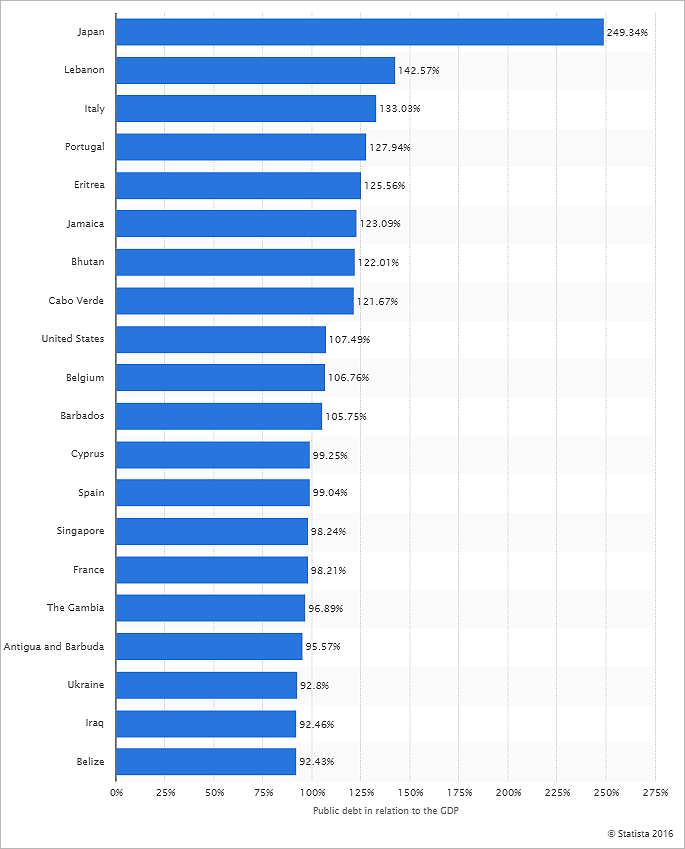

The perplexing status of the yen as a safe-haven currency is driven in part by Japan’s record debt levels. In terms of debt-to-GDP, Japan is blazing the trail. In fact, they’re so far ahead of the pack it’s difficult to see them.

Then consider that Japan is constantly flirting with recession, doing everything in their power to battle deflation, and interest rates are so low nearly two-thirds of the country’s debt trades at negative yields.

So then why, in times of economic uncertainty, does everyone want to own the yen?

The answer to this question is multifaceted. But before getting into the details, we need to accept that yen strength is simply not a function of domestic economic performance. As counterintuitive as that may sound, it’s the reality of the situation.

Current Account Surpluses

Japan has always been a large exporter and has continually exported significantly more goods and services than it imports. The result has been decades of current account surpluses that have positioned Japan as a net creditor to the world.

This is a distinction also shared by the Swiss franc, often considered another haven currency.

The value of foreign assets held by Japanese investors is substantially higher than the value of Japanese assets owned by foreign investors. These so-called “net foreign assets” stood at 339 trillion yen at the end of 2015, based on data from the Finance Ministry.

This places Japan as the largest creditor nation, a title it’s held for the last 25 years.

Read Lessons from Japan: Decades of Decay, Endless Monetary Expansion

The behavioral ramifications of this are simple: when markets become risk-averse, that money tends to move back home. This repatriation of capital coincides with a flow out of other currencies and into the Japanese yen, causing it to strengthen.

It may sound odd that the world’s most indebted nation (based on debt-to-GDP) is also the world’s largest creditor nation. This dichotomy stems from the fact that Japan’s massive debt is held almost entirely by the Japanese public.

As the New York Times said, “The Japanese government is in deep debt, but the rest of Japan has ample money to spare.”

The Carry Trade

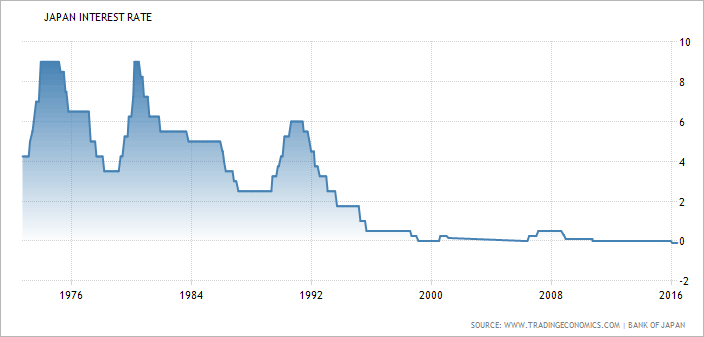

In addition to blazing the trail in terms of debt-to-GDP ratios, Japan has also been a leader in terms of low-interest rates. Attempting to stave off deflation and spur economic growth, Japan has held interest rates at rock-bottom levels for nearly 20 years.

The chart below shows that Japan’s discount rate has been at or near zero for the last two decades.

In what’s known as a carry trade, investors will borrow money in a low-interest rate environment and then invest that money in higher yielding assets from other countries. Japan’s long-standing policy of near-zero interest rates has caused it to become a major source of capital for these types of trades.

When uncertainty subsequently hits global markets, it can cause investors to unwind these trades, which then results in additional demand for the yen.

Perception and Self-Fulfilling Prophecies

With technical analysis and the reading of chart patterns, investors are often taught to ignore the fundamentals, and instead, simply follow the price action.

Don't miss Global Liquidity Update - Japan, Euro Area, and Emerging Markets All Negative

Similarly, in other situations we often feel comfortable ignoring the “why” when we notice a repetitive pattern of cause and effect. Sure, it’s more comforting to understand why a certain relationship exists, but that’s not a prerequisite for profiting from the relationship.

Part of the reason the yen continues to act as a safe-haven currency is simply because everyone acknowledges that it is. Investors around the world have come to embrace the yen as a reliable place to go for safety, and by attempting to take advantage of this, they actually create the intended effect.

If you know that whenever the world panics, the yen is going to rise, then it makes it a no-brainer to buy the yen even if you’re unsure exactly why everyone else is.

Conclusion

A number of factors are responsible for creating the dynamic in which investors flock to the Japanese yen during periods of global risk aversion. While some of these factors make sense from a fundamental perspective, others are simply the result of our ability to identify and exploit patterns.

Regardless of the exact reasons why investors view the yen as a safe-haven currency, the fact is that they do. And because the dynamics underlying this behavior are unlikely to change drastically in the near future, there’s a good chance the yen will remain a safe-haven currency for some time.

The preceding content was an excerpt from Dow Theory Letters. To receive their daily updates and research, click here to subscribe.