The essence of ultimate decision remains impenetrable to the observer — often, indeed, to the decider himself.

― John F. Kennedy (1917 – 1963)

Yet each man kills the thing he loves

By each let this be heard

Some do it with a bitter look

Some with a flattering word

The coward does it with a kiss

The brave man with a sword

― Oscar Wilde, “The Ballad of Reading Gaol” (1898)

We’ll get the kiss, not the sword. Don’t know when, but it’s going to kill this market that the Fed loves.

In 1969, Graham Allison published an academic paper about the Cuban Missile Crisis, which he turned into a 1971 book called Essence of Decision. That book made Allison’s career. More than that, the book provided a raison d’être for the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard, which — combined with Allison’s fundraising prowess — transformed a sleepy research institute into the most prominent public policy school in the world.

The central idea of Essence of Decision is this: the dominant academic theory to explain the world’s events is a high-level, rational expectations model based on formal economics, a theory that ignores the impact of bureaucratic imperatives and institutional politics. If you look at the Cuban Missile Crisis through all three lenses, however, you get a much better picture of what actually happened in October 1962. In fact, the more you dig into the Cuban Missile Crisis, the more it seems that the actual people involved (on both sides … Allison wrote a follow-up edition in 1999 when Russian archives opened up post-Gorbachev) made their actual decisions based on where they sat (bureaucracy) and where they stood (internal politics), not on some bloodless economic model. Publicly and after the fact, JFK and RFK and all the others mouthed the right words about geopolitical this and macroeconomic that, but when you look at the transcripts of the meetings (Nixon wasn’t the first to tape Oval Office conversations), it’s a totally different story.

Allison’s conclusion: the economic Rational Actor model is a tautology — meaning it is impossible to disprove — but that’s exactly why it doesn’t do you much good if you want to explain what happened or predict what’s next. It’s not that the formal economic models are wrong. By definition and by design, they can never be wrong! It’s that the models are used principally as ex-post rationalizations for decisions that are actually made under far more human, far more social inputs. Any big policy decision — whether it’s to order a naval blockade or an air strike on Cuba, or whether it’s to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima AND Nagasaki, or whether it’s to raise interest rates in September or December or not at all — is a combination of all three of these perspectives. But for Allison’s money, we’d do better if we focused more on the bureaucratic and political perspectives, less on the rational expectations perspective.

Allison is writing this in 1969! And here we are, almost 50 years later, still consumed by a theology of formal economic models, still convinced that Fed decision-making can be explained or predicted by our armchair analysis of Taylor Rule inputs. From an anthropological perspective, it’s pretty impressive how the high priests of academic economics have expanded their rule. From a human perspective, it’s awfully depressing.

What follows is my analysis of the Fed’s forthcoming decision on interest rates from a bureaucratic and an internal politics perspective. Seen through these lenses, I think they hike. Maybe I’m wrong. These things are always probabilistic shades of gray, never black and white. But what I’m certain about is that the bureaucratic and internal politics perspectives give a different, higher probability of hiking than the rational expectations/modeling perspective. So heads up.

First the bureaucratic perspective.

What I’m calling the bureaucratic perspective, Allison calls the “Organizational Behavior” perspective. His phrase is better. It’s better because entities like the Federal Reserve are, of course, large bureaucracies, but what we’re trying to analyze here is not the level of do-nothing inertia that we usually associate with the word “bureaucracy”. What we’re trying to analyze is the spirit or culture of the organization in question. What is the institutional memory of the Fed? What do personnel, not just the Fed governors but also the rank-and-file staffers, believe is the proper role of the institution? Most importantly, how do these personnel seek to protect their organization and grow its influence within the jungle of other organizations seeking to grow their influence?

The spirit, culture, and personnel composition of the modern Federal Reserve is almost identical to that of a large research university. That’s not a novel observation on my part, but a 30-year evolution commonly noted by Fed watchers. Why is this important? It’s important because it means that the current marriage between Fed and markets is a marriage of convenience. As an organization, the Fed doesn’t really care whether or not markets go up or down, and as an institution it’s not motivated by making money (or whether or not anyone else makes money). Like all research universities, the Fed at the organizational level is motivated almost entirely by reputation. Not results. Reputation. A choice between “markets up but reputation fraying” and “markets down but reputation preserved” is no choice at all. The Fed will choose the latter 100% of the time. I can’t emphasize this point strongly enough. From a bureaucratic perspective, the Fed absolutely Does. Not. Care. whether or not the market goes up, down, or sideways. When they talk about “risk” associated with their policy choices, they mean risk to their institutional reputation, not risk to financial asset prices. And today, after more than two years of a “tightening bias” and “data dependency”, there’s more reputational risk associated with staying pat than with raising rates in a one-and-done manner.

Why? Because the public Narrative around extraordinary monetary policy and quantitative easing has steadily become more and more negative over the past three years, and the public Narrative around negative rates in particular is now overwhelmingly in opposition. When I did my Narrative analysis of financial press sentiment surrounding Brexit prior to that vote, I always thought that would be the most hated thing I’d ever see. Nope. I’ll append the Quid maps and analysis at the end of this note for those who are interested in digging in, but here’s the skinny: the negative sentiment around negative rates is now greater than the negative sentiment around Brexit. The public Narrative around ever more accommodative monetary policy has completely turned against the Fed. And they know it.

It’s not only the overall Narrative network that has turned with a vengeance against the Fed, but also some of the most prominent Missionaries, to use the game theoretic term. Over the last few weeks we’ve seen Larry Summers take Janet Yellen directly to task, as the runner-up in the Obama Administration Fed Chair sweepstakes has apparently taken to heart the old adage that revenge is a dish best served cold. More cuttingly, if you’re Yellen, is the heel turn by Fed confidante and WSJ writer Jon Hilsenrath. His August 26th hit piece on the Yellen Fed feature article — “The Great Unraveling: Years of Missteps Fueled Disillusion with the Economy and Washington” — is the unkindest cut of them all.

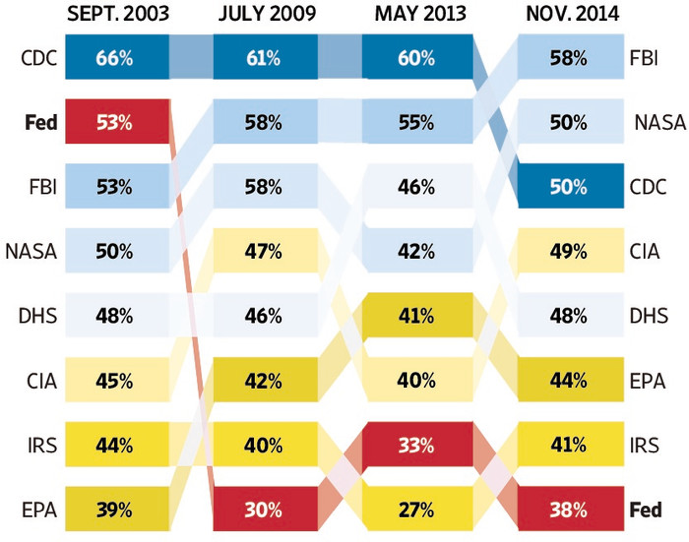

I think that Summers has been emboldened and Hilsenrath has been turned because they’re picking up on the same sea change in public opinion that the Quid analysis is identifying with more precision. For Hilsenrath, here’s the centerpiece of his j’accuse: a long-running Gallup poll asking Americans to rate the relative competence of federal agencies. Yep, that’s right, the Fed — which used to have a better reputation than the FBI and NASA — is now at the absolute bottom of the heap, dragging behind (by a significant margin) even the IRS! It’s one thing to bring up the rear in 2009 polls, what with the immediate aftermath of the deepest recession in 70+ years. But to still be at the bottom in 2014 after a stock market triples (!) and The Longest Expansion In Modern American History™? Incredible. And the most recent poll was in 2014. If anything, the Fed’s reputation is even lower today. I mean … this is really striking, and I can promise you that none of this is lost on the current custodians of the Fed’s prestige and reputation. Or, like Summers, the wannabe custodians. If you’re a professional academic politician like Summers, you can smell the blood in the water.

How Americans Rate Federal Agencies

Share of respondents who said each agency was doing either a ‘good’ or ‘excellent’ job, for the eight agencies for which consistent numbers were available.

Source: Gallup telephone polls, most recently 1,020 U.S. adults conducted Nov. 11—12, 2014, with a margin of error of +/-4 percentage points. As reported by the Wall Street Journal.

So what does all this mean for the September FOMC meeting?

Look … does “the market” want more and more supportive policy? Of course it does. We’re addicts. But if the Fed takes a dovish stance now — and anything less than a hike is going to be perceived as a dovish stance — from an organizational perspective the Fed is risking a lot more than a market sell-off from a rate hike. It risks being blamed for anything bad that happens in the economy going forward. This is the risk of being an unpopular political actor. This is the risk of losing your reputation for competence. The Golden Rule of organizational behavior is quite simple: there must ALWAYS be plausible deniability for culpability if something goes wrong. There must ALWAYS be some other political actor to blame. Unless the Fed takes steps now to stem the erosion in their reputation and their position in the public Narrative, they will own this economy and the downturn that everyone (including the Fed) suspects is coming.

By raising rates now, on the other hand, the Fed can declare victory. We achieved our dual mandates of price stability and full employment! Mission accomplished! And unlike George Bush and his infamously premature declaration of same, the Fed has someone to blame when the “mission” unravels (which of course it will) — those dastardly fiscal policymakers who didn’t follow up with structural reforms or pro-growth policies or whatever when they were elected this November. While the consensus view is that the Fed loathes to do anything to rock the market boat before the November election, in truth this meeting is the perfect time to act if your political goal is to declare victory and pass the buck. Hey, we did our part, says the Fed. Prudent stewards of monetary policy and all that. Now, about that consulting gig at Citadel …

That’s the bureaucratic or organizational perspective. Here’s the internal political dynamic as I see it.

An internal politics perspective is similarly driven by questions of reputation, but at the individual level rather than the organizational level. In an academic organization like the modern Fed, your internal reputation is based entirely on how smart you are, as evidenced by the research you do and the papers you write and the talks you give, not on how effective you are in any practical implementation of organizational aims. It’s not that the Fed or major research universities are intentionally ignoring or trying to put down practical implementations like teaching or outreach to commercial bank staffers, but every hour you spend doing that is an hour you’re not spending impressing your colleagues and bosses with how smart you are. It’s just how the internal political game is played, and anyone who has achieved any measure of success in an organization like this knows exactly what I’m talking about.

What this means in practice is that FOMC meetings are driven by a desire to form a consensus with the other smart people around the table, so that each of you is recognized by the other members of the consensus as being smart enough to be a member of the consensus. It’s the precise opposite of the old Groucho Marx joke: “I don’t want to be a member of any club that would have me as a member.” Every FOMC member desperately wants to be a member of the club that would have him or her as a member, because it means that you’ve been recognized as one of the smart kids. The internal political dynamic of academic cultures like the Fed, at least at the highest levels of Governor to Governor interaction, is NOT antagonistic or divisive. On the contrary, it’s cooperative and consensus-forming.

Not sure what I’m talking about? Read this Jon Hilsenrath interview of St. Louis Fed Governor Jim Bullard again (I say again because I published it for other reasons in the last Epsilon Theory note, Magical Thinking), where Bullard describes this consensus building dynamic.

Mr. Hilsenrath: What kind of compromise would it take to get the FOMC to move in September? I mean, so the tradition is there’s some kind of — like you say, some kind of agreement. What would it take to get them there?

Mr. Bullard: Well, I have no idea, so — and it’s really — it’s really the chair’s job to fashion that. But I will say that — I’ll talk historically about the FOMC, the kinds of things that the FOMC would do. You would trade off. You would say, OK, we could hike today, but then we’ll not plan to do anything in the future. That would be one way to — one way to go about a consensus. So that often happens on the FOMC. Or vice versa. If you read the Greenspan-era transcripts, he’ll do things like, OK, we won’t go today, but we’ll kind of hint that we’re pretty sure we’re going to go next time.

Mr. Hilsenrath: Right.

Mr. Bullard: And so you get this inter-tempo kind of trade-off, and that often — that often is enough to get people to sign up.

Mr. Hilsenrath: So, hike today and then delay.

Mr. Bullard: Yeah. (Laughs.)

Mr. Hilsenrath: Or, no hike today and then no more delay.

Mr. Bullard: Yeah, yeah.

Mr. Hilsenrath: Something like that.

Mr. Bullard: Yeah, those kinds of trade-offs are, historically speaking — I’m not saying I know what Janet’s doing, because I don’t. But, historically speaking, those are the kinds of things that the FOMC has done.

Mr. Hilsenrath: I came up with my catchphrase for the — for the month. (Laughter.)

Mr. Bullard: Those are great. That’s worthy of a T-shirt. (Laughs, laughter.) You could have one on the front and one on the back.

Ms. Torry: Or a headline.

Mr. Hilsenrath: Well, that’s the St. Louis framework now, right?

Mr. Bullard: Yeah.

Mr. Hilsenrath: Hike today and then delay.

Mr. Bullard: Yeah. That’s what it would be, yeah.

― Wall Street Journal, “Transcript: St. Louis Fed’s James Bullard’s Interview from Jackson Hole, Wyo.” (August 27, 2016)

What Bullard is describing from a game theoretic perspective is a dual-equilibrium coordination game. Either it’s “Hike today and then delay” (Bullard’s preferred equilibrium outcome) or “No hike today and then no more delay”. Those are the two possible consensus outcomes. Both are stable equilibria, meaning that once you get a consensus at either phrase, there is no incentive for anyone to change his or her mind and leave the consensus. Importantly, both are robust equilibria in their gameplay, meaning that it only takes one or two high-reputation players in the group to commit to one outcome or the other in order to start attracting more and more reputation-seeking players to that same outcome. You can think of individual reputation as a gravitational pull, so that even a proto-consensus of a few will start to draw others into their orbit.

It’s always really tough to predict one equilibrium over another as the outcome in a multi-equilibrium game, because the decision-making dynamic is solely driven by characteristics internal to the group, meaning that there is ZERO predictive value in our evaluations of external characteristics like Taylor Rule inputs in 2016 or US/Soviet nuclear arsenals in 1962. (I wrote about this at length in the context of games of Chicken, like Germany vs. Greece or the Fed vs. the PBOC, in the note Inherent Vice). But my sense — and it’s only a sense — is that the “Hike today and then delay” equilibrium is a more likely outcome of the September meeting than “No hike today and then no more delay”. Why? Because it’s the position both a hawk like Fischer and a dove like Bullard, both of whom are high-reputation members, would clearly prefer. If one of these guys stakes out this position early in the meeting, such that “Hike today and then delay” is the first mover in establishing a “gravitational pull” on other members, I think it sticks. Or at least that’s how I would play the game, if I were Fischer or Bullard.

Okay, Ben, fair enough. If you’re right, though, what do we do about it? How are markets likely to react to the shock of a largely unanticipated rate hike?

In the short term, I don’t think there’s much doubt that it would be a negative shock, because as I write this the implied “market odds” of a rate hike here in September are not even 20%. My analysis suggests that the true odds are about three times that, as I give a slight edge to the “Hike today and then delay” equilibrium over “No hike today and then no more delay”. Do I think it’s a sure thing that they hike next week? Give me a break. Of course I don’t. But if I can be dealt enough hands where the true odds of something occurring are three times the market odds of something occurring …

The medium-to-long term market reaction to whatever the Fed decides next week is going to be driven less by the hike-or-no-hike decision and more by the Fed-directed Narrative that accompanies that rates decision. That is, if they hike next week and start talking about how this is the next step of a “normalization” process where the Fed will try to get rates back up to 3% or 4% in a couple of years … well, that’s a disaster for markets. That’s a repeat of the December rate hike fiasco, and you’ll see a repeat of the January-February horror show, where the dollar is way up, commodities and emerging markets are way down, and everyone starts freaking out over China and systemic risk again. But if they hike next week and start talking about how they’re rethinking the whole idea of normalization, that maybe rates will be super-low on a semi-permanent basis, or at least until productivity magically starts to improve … well, that’s maybe not such a disaster for markets. Ditto if they don’t hike next week. If the jawboning associated with a no-hike in September sets up a yes-hike in December as a foregone conclusion, that’s probably just as bad (if not worse) for markets than a shock today.

Of course, the Fed is well aware of the power of their “communication policy” and the control it exerts over market behavior. Which means that whenever the Fed hikes — whether it’s next week or next month or next meeting or next year — they’re going to sugarcoat the decision for markets. They’re going to fall all over themselves saying that they’re still oh-so supportive of markets. They’re going to proclaim their undying love for markets even as they take actions to distance themselves.

But here’s the thing. The Fed is now revealing its one True Love — its own reputation and its own political standing — and that’s going to be a bombshell revelation to investors who think that the Fed loves them. Investors are like Tom Buchanan in The Great Gatsby. We’re married to this really swell girl, and we get invited to these really great parties, but then we see that Daisy is truly in love with Jay Gatsby, not us. And everything changes. Maybe not on the surface, but deep down, where it really matters. I’m not saying that the Fed abandons the markets. After all, Daisy stays married to Tom. But everything changes in that moment of realization that she truly loves someone else, not you, and that’s what the next Fed hike will mean to markets.

That’s when the party stops.

Appendix: Quid Narrative Analysis

For a recap of how I’m using the Quid tool kit to analyze financial media narrative formation and evolution, please refer to the Epsilon Theory note The Narrative Machine. Below are two slides from Quid providing a quick background on the process.