- The reported shortfall for the California Public Employees Retirement System (Calpers) is 9 billion - but that is based upon investment assumptions that may be unlikely in current markets.

- As developed using a 40 year financial model and recent actual results, the real present value shortfall could be in the 0 billion to trillion range, which is 4X to 7X as great as reported.

- Calpers is used as a real world example to explore nationwide issues that could change our financial futures - and our choices - as investors, taxpayers and pension beneficiaries.

The California Public Employees Retirement System is the largest public pension in the United States. It is considered to be the bellwether for pensions nationwide, and among the most sophisticated of long-term investors.

Read How a Public Pension Crisis Is Driving an Epic Credit Boom

Calpers also faces an extraordinary dilemma. It is drastically underfunded, even using relatively aggressive assumptions about future long-term investment returns. These assumptions do not take into account the current policies of the Federal Reserve and other central banks. As analyzed herein, when lower returns are taken into account, there can be a multiplying of the shortfalls - and a multiplying of taxpayer burdens.

Above are the most recent full year results for Calpers, for the fiscal year ending June 30th 2016. Calpers has a target return of 7.5%. For the most recent fiscal year, they had an actual total return of 0.6%, meaning they came up short by 6.9%.

Calpers ended the fiscal year with assets of 5 billion, but they needed 4 billion to be fully funded - assuming they can earn 7.5% on average for each year in the future. The difference between those two amounts is a shortfall of 9 billion.

Another way of looking at this is that if we say 4 billion is 100 cents on the dollar, and the amount they actually have on hand is 5 billion, then their funding percentage is 68 percent (292/434 = 0.68). This compares to a national average funding percentage of 72 percent, so Calpers is just a little bit below the national average.

Read also The Big Disconnect in the Pension Industry

To better understand the dilemma that Calpers is facing and why it's likely considerably worse than 9 billion, we need to understand the nature of a pension fund - which is also very similar to the requirements of a long-term individual investor.

As retirement investors, we invest today so that we can slowly draw down our savings over a period of many years as a retiree. What Calpers is doing is investing money today to cover anticipated payouts to their pensioners over a very long period of time. The calculations involved are complex and require three types of projections - economic, actuarial and investment (with those same factors also being quite relevant for individual retirement investors).

To isolate the importance of the investment assumptions without getting bogged down in the complexity of the economic and actuarial assumptions, we are going to use a round number illustration of the dilemma faced by Calpers and other pension funds.

We are going to assume that Calpers is investing to cover even annual payouts over the next 40 years. Using a bit of reverse financial engineering, if 4 billion is full funding, and 7.5% is the investment rate, then 40 annual payments of .5 billion can be supported.

So this means total payments of .378 trillion can be supported, which are consolidated in the graph above.

Pension funds share an assumption with individual financial planning as well as other forms of long term investment to support obligations, and that is the idea that we can estimate today what our earnings will be not only next year and the year after, but (on average) for decades into the future.

So we don't need to set aside almost .4 trillion, but 4 billion will suffice. Because 4 billion invested at 7.5% and evenly drawn down over 40 years will generate 4 billion in earnings. Every dollar available today (the purple bar) is assumed to generate another .18 in earnings (the green bar) over the next 40 years, and that is the rationale that enables governments and corporations to make much larger promises for the future than the cash that is actually being set aside today.

However, Calpers doesn't actually have 4 billion. Instead, they have 5 billion, as shown in the purple bar above. There is a gap between what they have and what they need, which is a present value shortfall of 9 billion, as represented by the red bar. Full funding would be 100% or 4 billion, actual funding is 5 billion, or 68%, and the deficit is 9 billion, which is 32%.

We know the size of the purple bar, the investments on hand. We know that the red bar, the present value shortfall, is the difference between the green bar and the purple bar. But what we don't actually know is the size of the green bar. It is all an assumption, in terms of being able to earn the average of a 7.5% annual rate of return into the indefinite future.

Check out Andrew Scott: How Increasing Lifespans Affect Our Investments

We also know Calpers only earned 0.6% in their previous fiscal year. Calpers earned a negative return of -3.4% on their equity portfolio last year. Interest rates in the United States are at near historic lows. Global interest rates are at the lowest levels in recorded history when we include the negative interest rates in Europe and Japan.

From that perspective, a 7.5% investment assumption seems outdated or even antiquated. So a reasonable question becomes: what happens to the present value shortfall if actual returns are less than 7.5%?

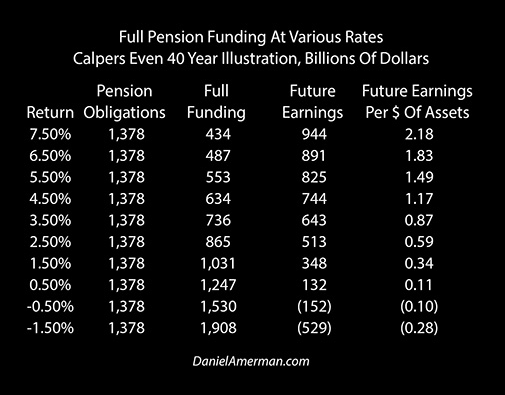

As the next step, we need to consider what our new full funding amount is at various possible future returns. Remember - full funding being 4 billion is only accurate if we get a 7.5% return, meaning .18 in future earnings for each dollar on hand today, as shown in the rightmost column above.

If we drop to a 6.5% average return over the next 40 years, then there is only .83 in future earnings for each dollar on hand today - and we therefore now need 7 billion to be fully funded.

Much more dramatic is what happens if returns average only 4.5%. In that case, there is only .17 in future earnings for each dollar on hand to today. So, to be able to make all promised pension payments, the State of California would need to have 4 billion set aside today.

Again, this is a very similar dilemma to that which is faced by many individual retirement investors. If we don't get the yields we assumed, then we either need to save a lot more money, or we may need to delay retirement, or we may need to reduce our retirement standard of living (or perhaps all three together). But yet, for many investors and savers today - a 4.5% rate of return would be highly desirable and quite difficult to achieve. What happens if we go much lower?

If Calpers were to roughly repeat last year's results and earn a 0.5% average return over and over again, then as shown with the purple bars, they would need to have .2 trillion set aside today to fully fund the promised pension payments.

At 1.5%, the State of California would still need to have over trillion set aside to invest and use to make future payments. By going up to an average 2.5% return over 40 years, the amount of future earnings (the green bars) would dramatically increase - from 8 billion to 3 billion - but 5 billion (the purple bar) would still need to be available to invest today.

The far left columns with returns of -0.5% and -1.5% may seem quite bizarre, but such is the world in which we live today. The concept of negative interest rates is I think hard for most of us to grasp, but that is exactly what is happening with government debt in Europe and Japan.

See End of Debt Supercycle Means Low Rates for Years to Come

Based on current interest rate levels, there has been a discussion that if the United States enters another recession, then negative interest rates may come here as well. And if that were to happen and if low or negative economic growth were to also bring stock yields into negative territory, then there is an inversion, and more money must be set aside today than what will be paid out in the future.

Meaning full funding could require .5 trillion, or even trillion. (The preceding is based on nominal interest rates, however, in real or inflation-adjusted terms the United States already has negative returns and an inversion for many investors has already occurred, as explored in this link.)

However, Calpers doesn't have trillion set aside today, or trillion, or 0 billion. It has 5 billion.

When we assume an average 6.5% return, the needed assets grow to 7 billion, but we still only actually have 5 billion, so then our present value shortfall grows to 2 billion, and the pension is only 61% funded.

At a 4.5% average return, then our shortfall shoots up to 9 billion, and Calpers is only 47% funded, or less than half.

The shortfalls grow to stunning amounts when we reach the lower returns, as can be seen above. The purple bars of what Calpers has on hand today is fixed in each possible investment return scenario. The green bars shrink with great speed as assumed future investment returns are brought down. And it is the red bars of the present value shortfall that must expand to cover the gap.

If Calpers were to repeat its investment results from last year, year after year, then the red bar of true PV shortfall is 2 billion. That is close to trillion and is almost 7X greater than the current official shortfall of 9 billion.

At a 1.5% average return, the green bars of future earnings would almost triple from 2 billion to 8 billion - but the present value shortfall is still 6 billion. With a 2.5% average annual return over 40 years the future interest earnings rise to 3 billion - but that still leaves a shortfall today of 0 billion, or more than 4X the official shortfall.

Now if interest rates or investment returns were more or less random, or following market norms, then this would hopefully not be a problem. The last fiscal year was very low, maybe the next fiscal year would be very high, and on average, over time, everything would work out.

The problem, however, is these are not normal times.

In the immediate aftermath of the financial crisis of 2008, the Federal Reserve pushed interest rates to some of the lowest levels seen in history. And despite frequent claims that rates are about to be raised, rates have hardly increased in the last eight years. In Europe and Japan, they have moved even lower over the last year.

What this creates is a toxic combination when it comes to Calpers, other public and private pension funds, and long term investing in general - including financial planning for retirement accounts.

Many government bodies, including states, cities and school districts, are all making binding promises about decades of payments to public employees which are based upon relatively high investment yields generating much of the cash. Simultaneously, another part of government - the Federal Reserve - is massively intervening in the markets, and pushing yields to all-time lows. These federal policies have a potentially catastrophic impact on public finances on a nationwide basis, yet are being generally ignored with current pension shortfall estimates of state & local governments.

These issues can directly impact individuals and particularly individual retirees in at least three ways. The first impact is that individuals and advisors routinely use long-term historical returns as reasonable assumptions - but those returns don't include the current market-dominating interventions by central banks on a global basis. Which means they could very easily be dead wrong, and individual plans could be as underfunded as pension plans.

The second impact is even as cash available from investing may be less than hoped for, the cash needed in retirement may be higher than expected because of higher tax rates.

The third impact is that impossible public promises will not necessarily be paid, and the new bail-in methodology that has been adopted by the United States and other G-20 nations could slash pension payouts as well as other sources of retirement security, as explored here. So for someone who is investing to supplement their pension, they could see the three-way combination of lower investment earnings, higher tax rates and reductions in their pension payments. And again, these issues are not restricted to California and Calpers but could impact any pensioner (or taxpayer) in just about any state.

These are not pleasant topics. But what needs to be recognized is that the Federal Reserve forcing extremely low returns on the nation as a matter of policy comes with high costs for pensions and taxpayers specifically, as well as all long term investors in general, including individual retirement investors. Yet, there is little public pushback, and arguably the reason is that the public doesn't have sufficient understanding of what is happening.

This analysis is intended to help close that knowledge gap, and it is also one piece of a much larger and interwoven body of work. Another key component, linked here, is understanding the financial conflict of interest between pensions (and other savers), and a heavily indebted federal government, where pensions and savers getting the higher returns they so badly need, could send the national debt spiraling out of control.