Highlights

- 5G communications networks will enhance the performance of the internet of things, autonomous vehicles and other technological advancements in the 2020s.

- Having lagged behind its rivals in developing 5G’s predecessors, China will exert greater effort to set the parameters for the development of the new network.

- The United States will consider various precautions to prevent China from gaining too much ground in the race to develop 5G.

The race has well and truly begun. China, the United States, South Korea and a handful of telecommunications companies are rolling up their sleeves to develop, test and deploy the technology that will drive the world’s economy in the decade to come: 5G mobile communications networks. With 5G representing a great leap forward over its relatively pedestrian predecessors, countries and companies with ambitions in the field are well aware of the need to stay ahead of the pack for what is certain to be a strategic resource. And few countries have been as bullish on pursuing 5G as China – an ambition that has stoked more than a few fears in Washington.

The Big Picture

Stratfor is closely following the fourth industrial revolution, which will usher in robotics, 3-D printing, automation, the "internet of things" and other related technologies that will radically change the way economies behave in the decades to come. The 5G communications networks that will underpin numerous applications of these technologies could, like many other areas, become an arena for battles between the United States and China.

See The Fourth Industrial Revolution

The 5G Difference

Roughly every decade over the past 30 years, a new global mobile communications network has emerged to replace a previous generation. The first generation of mobile networks that debuted in the 1980s had the capacity to carry voice phone calls only, while their second-generation successors in the mid-1990s allowed users to send basic data packages consisting of text messages and partial internet services. As the new millennium began, 3G networks became ubiquitous; voice remained paramount, but the technology offered users the first mobile broadband access for multimedia and the internet. In the most recent decade, 4G or 4G LTE networks – whose overriding focus has been data to the extent that voice has become an afterthought – have put smartphones in the hands of much of the world’s population.

The latest stage in the evolution of mobile communications networks, 5G, will go further than any of the previous generations of networks with its handling of three different communications types: enhanced mobile broadband, massive machine-type communications, and ultra-reliable and low latency communications.

The enhanced mobile broadband platform is the latest in the natural evolution of 4G/LTE technologies that facilitate mobile broadband – except that the latest generation is much faster. Already, San Diego-based Qualcomm has been testing simulations of 5G's real-world performance in certain cities using the location of existing cell sites and the spectrum allocation for mobile networks. According to Qualcomm’s simulation for San Francisco, users could enjoy a significant increase in browsing speeds (rising from 71 megabits per second (Mbps) for 4G to 1.4 gigabits per second for 5G) and download speeds (from 10 Mbps to 186 Mbps). But there’s more: Video streaming will reach an average quality level of 8K resolution, 120 frames per second and 10-bit color. The figures do not portend a mere improvement in the streaming of media but will unlock real-world applications on a massive scale. Augmented and virtual reality will also benefit from the emergence of the mobile broadband improvements.

Massive machine-type communications will aid in the development of the "internet of things," the network of interconnected devices embedded in everyday objects that share data, as well as smart devices, sensors and industrial equipment that uses the mobile network. Many of these devices do not require ultra-low latency (the amount of time it takes to send a message through the system and for the receiving machine to follow instructions) since a sensor might only send data every hour. However, the 5G network will improve the functions of such devices, especially if many of them are located close to each other physically.

Ultra-reliable and low-latency communications will form the backbone of new applications. The goal of 5G networks will be to increase reliability and reduce latency to less than 1 millisecond, which is far more rapid than the comparatively sluggish figure of 25 milliseconds – even in ideal conditions – for existing 4G technology. Accordingly, ultra-reliable connections could become instrumental for “mission critical” applications due to the effective elimination of any element of risk. Low-latency connections will lead to the greater usage of self-driving cars, as well as the tactile internet, which will enable people to control objects remotely as never before. The tactile internet, for instance, could soon allow surgeons to perform operations from thousands of miles away in real-time.

China Goes From Strength to Strength

On a wider scale, 5G networks will hold together many of the technological innovations that will define the world in the decade to come, including the internet of things, outdoor autonomous robots for agriculture and industry, the smart utility grid, and autonomous vehicles and drones. And with the significance of 5G far outweighing that of any of its predecessors, nation-states are taking notice as they race to roll out their own networks to establish a first-mover advantage.

Unsurprisingly on account of its internal imperatives and grand strategy, China has made 5G a central plank of its overall industrial plans, including Made in China 2025 and its 13th Five-Year Plan, amid its desire to commercially deploy 5G technologies by 2020. Several Chinese companies have taken a leadership role in developing some of the technologies – a development that has not escaped Washington's attention.

Beijing has opted for an international approach to development and deployment of 5G. China has assumed a pioneering role in various international organizations that are developing the standards to underpin 5G technology, such as the 3rd Generation Partnership Project – the organization that facilitates collaboration by industry participants on telecommunications standards – and the International Telecommunication Union. Carriers whose operations are restricted to a handful of countries often operate the world’s current mobile telecommunications networks, unlike the basic equipment that is central to the telecommunications industry. Radio access network technologies, such as antenna base stations, core chipsets, and mobile handset/smartphone devices, are produced in a globalized market, ensuring a high degree of standardization and interoperability on a worldwide level.

Previously, China attempted to develop its own indigenous standards for technology, especially 3G, even though it was not a market leader – producing scant success. China tried to force a global standard upon 3G mobile networks, but its proposed parameters failed to catch on even in at home, let alone globally. In the end, 3G technology did not arrive in that country until six years after it had commercially emerged around the globe. Accordingly, China remained largely dependent on foreign intellectual property. In rolling out standards for 4G, China played a more active role, although it trailed well behind its Western peers in terms of base technology.

This time, Beijing appears to have learned from the past. China is hoping to lead from the outset on 5G by helping set standards that are better-suited to Beijing’s desires for the network, thereby allowing it to leap ahead of its many global competitors. China could push for parameters that emphasize the industrial applications of massive machine communications and ultra-reliable low-latency communications over the media applications of enhanced mobile broadband, which means focusing less on the millimeter wave band – part of the spectrum above 24 gigahertz – and more on a system called Massive Multiple In Multiple Out, under which there could be hundreds of antennas and receivers operating from the same base station, instead of the current two to four antennas.

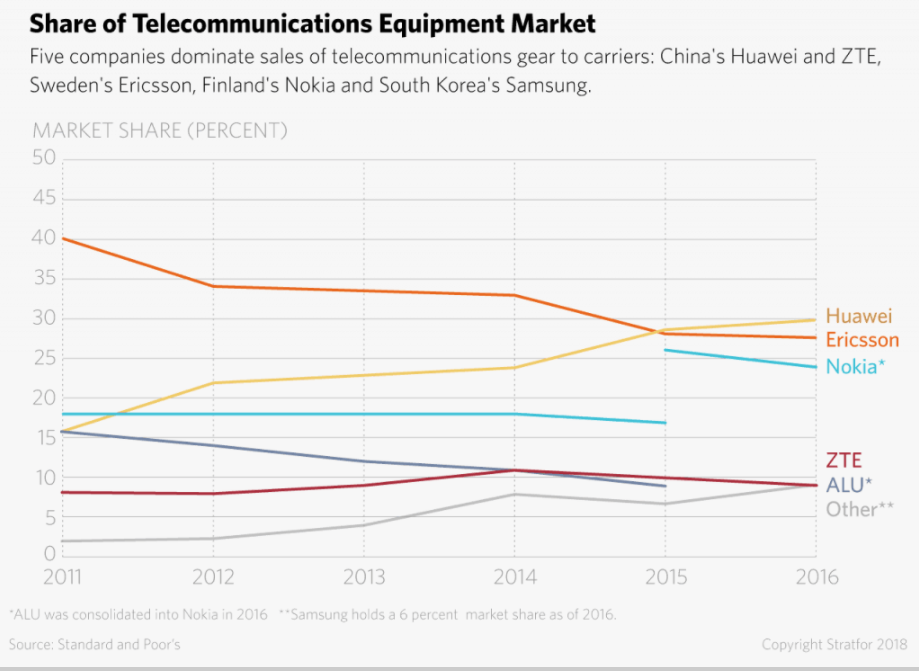

China is already a leader in antenna and base station architecture with Huawei and ZTE, whose only global competitors are South Korea’s Samsung, Finland’s Nokia and Sweden’s Ericsson. Although the Scandinavian equipment vendors have a small lead when it comes to memorandums of understanding on 5G and pilot tests with global carriers, Huawei surpassed Ericsson in 2016 to become the world’s biggest producer in mobile equipment, gaining a global market share of roughly 30 percent.

Wariness in Washington

Huawei has provoked particular concern in Washington due to its leadership in 5G trials and its status as a leading radio access network vendor. Since 2012, U.S. politicians have expressed worries about using ZTE and Huawei equipment on U.S. networks out of concerns about the potential security risk. As a result, a de facto ban on Huawei and ZTE’s equipment in the United States could become more permanent in the country amid growing U.S. nationalism that seeks to close the door to Chinese technology – even though the two companies have inked global partnerships and business deals in Canada, Japan and Europe for 5G. The White House has even reportedly considered nationalizing the United States' 5G network and is also considering invoking emergency powers to restrict further Chinese investment in such sensitive sectors.

But Huawei and ZTE are not Washington’s sole concern. While U.S. firms like Intel and Qualcomm are critical players in the 5G system overall, the United States does not have a major domestic manufacturer of 5G radio access network hardware. Accordingly, the United States is voluntarily walling itself off on 5G by eschewing Huawei and ZTE, since there are only three other companies, Samsung, Nokia, and Ericsson, that are currently exploring end-to-end solutions for 5G.

The United States will seek to protect what remains of the 5G industry in the country, even if the manufacturing process is not always based there. This is one reason Washington has focused so strongly on China’s intellectual property strategy and technology transfer, especially when companies like Qualcomm do not always manufacture the semiconductors that they design, instead outsourcing them to pureplay foundry companies (which produce semiconductors using someone else’s designs), some of which are based in China.

Corporation vs. Corporation

But it is not just nations that are battling over technology like 5G; many global giants in the industry – some hailing from the same country – are fighting each other for the chance to develop the new networks. Intel and Qualcomm, which have been rivals for decades, are now both important competitors for 5G technology, especially in the design of computer chips for various devices and base wireless technologies, like waveforms. Both will also earn lucrative royalties from patents, with Qualcomm frequently earning royalties even when its chips are absent from a product because it holds the patents in the corresponding wireless technology. In the end, Qualcomm wishes to earn as much as .25 per 5G smartphone as a result of its patents.

The company, however, has become a political hot potato since it mired itself in a number of disputes with rivals over its royalty-dependent business model. In February, Qualcomm announced that 19 global carriers and 18 original equipment manufacturers had agreed to select the Qualcomm Snapdragon X50 5G modem for their first rollout of 5G devices in 2019. Apple, Samsung, and Huawei, however, were not among any of the 18 manufacturers, even though the three firms accounted for 45.3 percent of the worldwide market share for smartphones last year.

Apple and Qualcomm, whom the latter uses as one of its suppliers of modems for iPhone devices, have been embroiled in a protracted legal fight since January 2017 over royalties. Qualcomm has argued that it should receive royalties based on the overall value of the smartphone or device, not the value of the individual components, as Apple desires. The legal battle has gone global as Qualcomm has filed lawsuits in China in an attempt to ban iPhone sales. In a separate case, the European Union fined Qualcomm .2 billion in October 2017 for a rebate program partnership with Apple that would have ceased payments to the latter if it began selling products with other companies’ chips.

If Apple discontinues its partnership with Qualcomm, it is not clear who would provide modems for its 5G devices. A partnership with Intel might make the most sense (the two have been exploring a deal, according to speculation), and it is politically impossible to collaborate with Huawei on 5G technology. The South Korean and Chinese giants have also locked horns with Qualcomm, leading them to forego Qualcomm-based technology and develop their own 5G modems – something that Apple could also do.

Qualcomm’s challenges prompted a hostile takeover attempt by Broadcom earlier this year for 1 billion. Broadcom’s move, however, raised immediate concerns in Washington regarding the implications for U.S. national security and technological leadership following suggestions that it would cease funding for Qualcomm’s 5G research and development, thereby allowing a Chinese competitor like Huawei to potentially emerge and supplant Qualcomm as an industry leader. Broadcom, a Singapore-based company, had promised to move its headquarters to the United States and continue investing in 5G to help facilitate the deal, but the pledges failed to persuade U.S. President Donald Trump, who nixed the deal with an executive order in March. The decision also relieved Intel, which had even toyed with the idea of acquiring Broadcom just so it could scuttle the deal and prevent the emergence of a new colossus in its midst.

A select group of states and firms in different parts of the world have an opportunity to lead the development of the communications network that will power the world of tomorrow. At present, integrated Chinese companies like Huawei – a competitor to Nokia, Ericsson and Samsung in network gear, a rival to Qualcomm and Intel on chip design and an emerging challenger to Apple and Samsung in end-user devices – are entertaining some of the biggest ambitions of developing new technology like 5G, much like U.S. companies did in previous generations. Given the extent of the Chinese challenge, it’s no wonder that Washington is taking a long look at 5G in the context of its broader battle with Beijing over trade and technology.

The U.S., China, and Others Race to Develop 5G Mobile Networks is republished with permission from Stratfor.com.