"In particular, the Committee decided today to keep the target range for the federal funds rate at 0 to 1/4 percent and currently anticipates that economic conditions–including low rates of resource utilization and a subdued outlook for inflation over the medium run–are likely to warrant exceptionally low levels for the federal funds rate at least through late 2014."

(Press Release, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 25 January 2012)

Something is wrong with our economy. Given the recent pronouncements by the Fed, it is unlikely to improve in the short or intermediate term. America is drowning in debt and our financial experts keep advocating larger doses of "debt heroin" to fix the problem. In the last decade, total outstanding debt has increased from $28 trillion in 2000 to approximately $54 trillion in 2010. During that same period of time U.S. GDP has grown from $9.9 trillion in 2000 to $14.6 trillion in 2010. It is now taking close to $6 of debt to produce $1 in GDP. This is clearly unsustainable. America's economy is now beginning to malfunction.

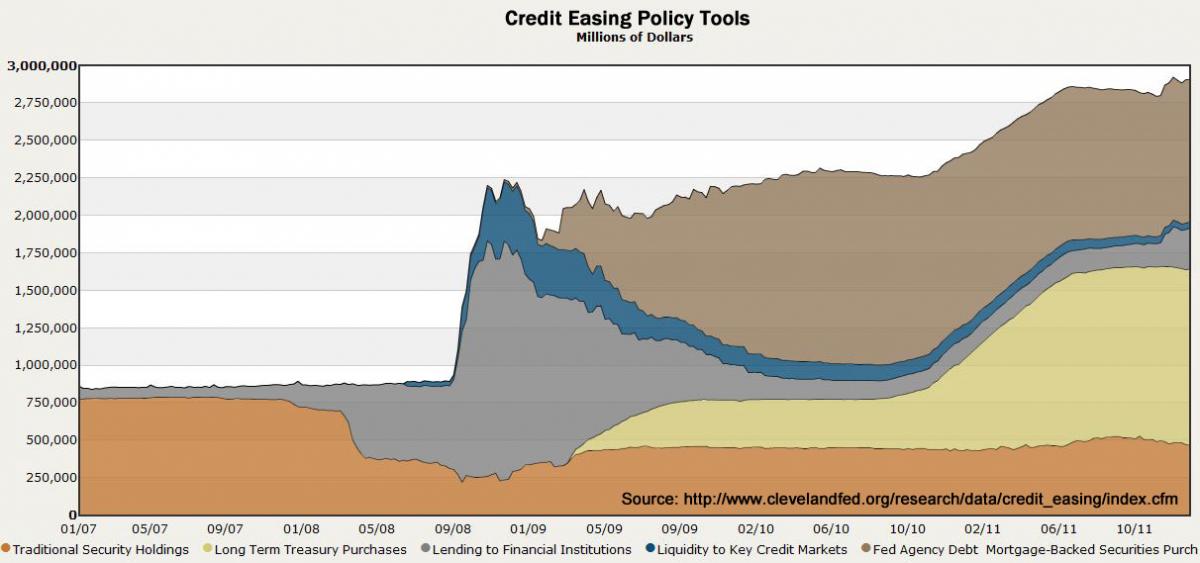

Since 2008 the Fed's balance sheet has also grown from $900 billion to $2.9 trillion, an increase of $2 trillion in a period of four years. During that same period U.S. federal debt has expanded from $10.0 trillion to $15.5 in 2011, and will increase by another $1.2 trillion in 2012.

Source: U.S. Government Spending

The Fed has expanded its balance sheet by trillion and the U.S. government has increased its outstanding debt by .7 trillion over the last four years. It has taken nearly trillion in monetary and fiscal stimulus to grow our economy from .2 trillion in 2008 to an estimated .3 trillion in 2011.

At the most recent Federal Open Market Committee meeting, the Fed lowered its growth targets for both 2012 and 2013. GDP growth for 2012 was lowered from expanding 2.5% to 2.9% down to an expansion of 2.2% to 2.7%. The 2013 forecast was reduced from 3.0% to 3.5% to a lower rate of growth of between 2.8% to 3.2%.

In addition, the unemployment rate is expected to edge down to between 8.2% and 8.5%. (See "Economic Projections" from the January 2012 FOMC meeting.) These anemic economic statistics have led the Fed to extend its zero-interest-rate policy from mid-2013 to late 2014. Clearly something is not working and it is becoming apparent that the problem is structural.

Uses of Debt: Produce, Innovate, Consume, or Speculate

As I wrote in my last article, "The Debt Supercycle Reaches Its Final Chapter," the problem with the U.S. is that the Debt Supercycle is heading into its final phase—a critical point at which debt becomes highly destructive to an economy.

For example, debt can be used to finance four different financial transactions:

1. productive investment

2. innovation

3. consumption

4. speculation

The first two add to the productive capacity of an economy. When the government builds roads, dams that produce hydro-electric power, or other infrastructure projects, debt is being used productively. Similarly, when debt is used by companies for research and development or new ventures, it may lead to the production of new goods or services, which then can lead to an expansion of GDP.

Debt that is used for consumption, however, is considered a dissipation of capital. Nothing is produced; rather, something is consumed. After something is consumed—such as a basic necessity like food—the debt remains even though the item consumed no longer exists. When debt is added for consumption purposes it enables the debtor to pull tomorrow's demand forward into the present. As debt is used to expand consumption in the present period, it is in essence borrowing from the future therefore reducing future demand.

Debt taken on for speculative purposes is also unproductive as it can lead to asset bubbles or overinflated prices for assets. Eventually all asset bubbles go bust. The overinflated asset values decline but the debt still remains. Think of the recent housing bust and the technology bubble as an example of speculative bubbles financed by debt for unproductive purposes.

Consumption: A Problematic Use of Debt

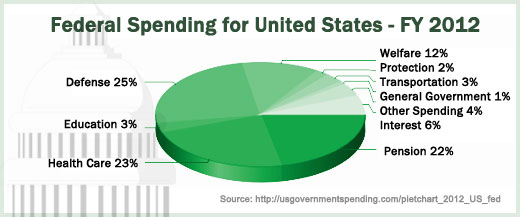

One of the main structural problems of the U.S. economy is that a larger portion of debt is being used to finance consumption. The biggest example of this is government transfer payments. For 2012 the Federal Government will spend 12% for welfare, 23% for health care, 22% on pensions, and 6% on interest on the debt.

Source: U.S. Government Spending

At the beginning of the last century total government spending equaled 6.9% of GDP. During the Great Depression spending rose to 20% of GDP, then to 53% in 1945 as a result of World War II. It would eventually drop and stabilize around 34–35% throughout most of the last three decades. Following the aftermath of the bursting of the housing and credit bubble, which led to massive bailouts of the financial and auto industry, spending surged to wartime levels of 45%. The bailouts are now behind us, but they have been replaced by transfer payments, with future spending pegged at around 40% of GDP. Total estimated spending by government (federal, state, & local) for 2012 is estimated to run over .2 trillion.

Transfer Payments a "Net Zero" Use of Debt

The majority of this spending will be made in the form of transfer payments to Social Security, Medicare & Medicaid, welfare, unemployment, and interest on debt. These transfer payments are one-way transactions. No goods or services will be produced in exchange for these payments. They are all one-sided. In his book Stabilizing an Unstable Economy, the late American economist Hyman Minsky warned of the danger of big government spending and the consequence of transfer payments in their impact on GDP.

"A transfer payment is a one-sided transaction, in contrast to an exchange, which is two-sided. In a transfer payment, a unit receives cash or goods and services in kind without being required to offer anything in exchange. A transfer payment recipient conforms exactly to the economic status of a dependent child. A unit receiving a transfer payment does not provide inputs into the production process. Because the recipient produces no outputs, transfer payment receipts are not part of the GDP, although they are part of a consumer's disposable (after-tax) income."1

Minsky elaborated further the impact of these transactions on income and employment within our economy:

"…when the government transfers income to people, there is no direct effect on employment and output. Nothing that is presumably useful is exchanged for the income, and the economic impact comes only as the recipient spends the funds that are transferred…

"In the standard view of how government affects the economy, government spending on goods and services is considered a component of aggregate demand, along with consumption and investment, but government transfer payments are not. The rules governing consumption spending are expressed as a function of disposable income, various measures of wealth or net worth, and the payoff from using income to acquire financial assets…

"Because of the way matters are measured, the impact on GDP of a dollar spent to hire leaf rakers in the public parks is greater than a dollar given in welfare or unemployment benefits. Minsky was alarmed at the transformation taking place within the U.S. economy as a result of the changing nature of government expenditures from the purchase of goods and services to one of transfer payments. The 1970s witnessed a trend change in government expenditures away from goods and services to what we refer to as "entitlement spending." This trend accelerated in the last decade and continues on an upward trajectory under the Obama presidency."2

The U.S. Economy Is an Economy of Consumption

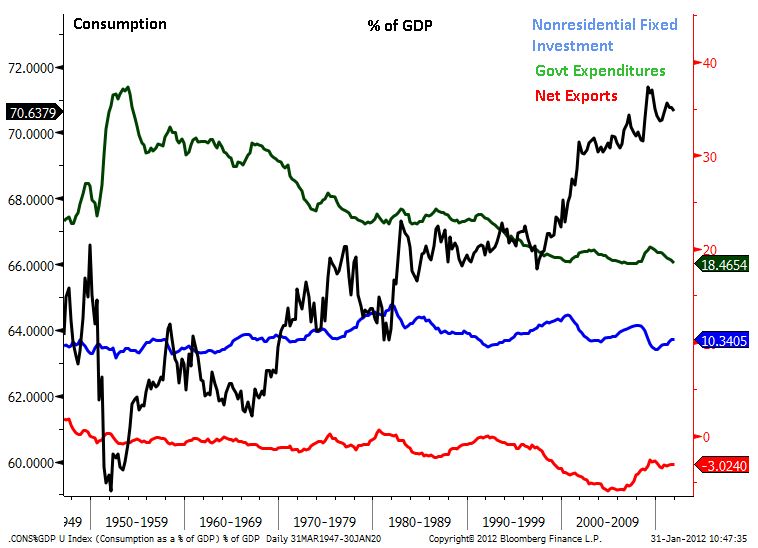

This leads to another major structural problem with the U.S. economy. In the 1950s the U.S. economy began to shift away from a manufacturing, investment, and a savings economy toward more of a consumption economy as shown in the graph below.

This trend began to stabilize during the 1980s and '90s. As a result of the exploding debt binge of the last and current decade it has once again begun to accelerate.

Today, consumption represents close to 71% of GDP, an increase of 10 percentage points over the last half-century. The U.S. economy has transformed from an economy that saves and invests to an economy that spends, borrows, and prints money: a lethal combination that can only lead to higher rates of inflation and a collapse of the currency, something Minsky both warned against and predicted.

As I argued in Part I of this essay, as the government moved from printing money to finance its deficits to a policy of financing debt through the bond markets, more of American savings and capital was diverted away from productive investment towards government debt. Economists refer to this as the "crowding out effect." This alarming trend can be viewed in the next graph which shows nonresidential fixed investment as a percentage of GDP.

As shown in the graph above, productive investment has been in decline after peaking in the late '70s—a period of time when more of American manufacturing began to be outsourced. There have been brief periods of time—as in the '90s and more recently—when investment has increased. However, the downward trend in investing is clearly obvious.

Government Debt and Spending Replacing Consumer Debt and Spending

The Debt Supercycle reached its apex in 2008 when consumer debt expansion came to a clear end. It has been superseded by an expansion of government debt. The problem the U.S. now faces is that its burgeoning deficits and growing debt balances have become so large that domestic savings and the bond markets are no longer capable of financing them. In order to do so, the U.S. now relies on foreign investors and foreign central banks to supply capital to the U.S. What cannot be financed through the debt markets is monetized by the Federal Reserve. This disquieting trend can be viewed in the following charts that show gross Federal debt, foreign ownership of U.S. treasuries, and the Fed's balance sheet.

Source: https://peakoil.com/forums

Source: Credit Writedowns

Source: CFR

Source: CFR

Fed Balance Sheet

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland

There are those who would argue that our growing debt is irrelevant; they point to the rush to buy treasuries by foreign investors in the third and fourth quarters of last year. As Europe's debt woes began to unravel, money poured into U.S. treasury markets. The money flowing into U.S. treasuries drove both the value of the U.S. dollar higher and the yield on U.S. treasuries even lower, despite a downgrading of our debt.

The U.S financial markets are the largest capital markets in the world. They are one of the few markets in the world that are capable of absorbing a large influx of capital. Because of their size and scope, especially our government debt market, U.S. Treasuries are considered a safe haven whenever financial turbulence resurfaces around the globe. The onslaught of foreign capital along with outflows in the global equity markets into U.S. treasuries enabled the Fed to forego quantitative easing as the economy slowed down mid-year. Yields fell, mortgage rates came down, and growing budget deficits were able to be financed.

This has enabled American politicians to continue their policy of tax, spend and borrow. The President has asked Congress to extend the debt ceiling by another .2 trillion so the government can pay its bills this fiscal year. Yet, our growing deficits will not be used and spent on productive investments that would grow GDP or bring the unemployment rate down. Most of this spending will be in the form of transfer payments.

This pattern of tax, spend, and borrow will not continue indefinitely. In its 2013 forecast the Fed cited higher taxes and government layoffs next year, as well as repercussions from Europe's debt crisis, as reasons why growth next year will be less than expected. The Fed is also setting the stage for some sort of additional monetary easing. Fed Chairman Ben S. Bernanke, speaking at a news conference after the statements, said that the option of further large-scale bond purchases is still "on the table."

Round III Quantitative Easing on the Way

If inflation is going to remain below target for an extended period and employment progress is very slow, then there is a case for additional monetary stimulus.

Prepare yourself. The next round of QE is baking in the oven. U.S. deficits and debt balances have grown too large and are no longer capable of being funded through the bond markets alone. Large quantities of money printing are now necessary to pay our bills.

As I have explained on the show, this deficit is structural. Furthermore, our debt levels are now growing exponentially. The U.S. government debt, which now stands at .3 trillion, could not withstand a surge in interest rates. At .3 trillion, a 1% increase in interest rates would add 0-0 billion to annual interest expense. As sobering as this statistic is, it becomes worse when you consider the U.S. is adding over trillion of fresh debt each and every year. The simple fact is we are dead broke but not quite bankrupt due to our ability to print money. We also enjoy the privilege of the U.S. dollar's role as the world's reserve currency. This allows the U.S. to finance its debt in its own currency.

This is a privilege that many nations believe is being abused by our monetary and fiscal largesse. Many major powers are now conducting bi-lateral trade in currencies other than the U.S. dollar. These are major economies from China, Japan, India, OPEC nations, to the emerging economies of Latin America. It may be a while longer before the dollar is replaced by a global currency, perhaps some time in this decade. But its days as the world's reserve currency are numbered. The U.S. is living on borrowed time.

[1] Stabilizing an Unstable Economy, Hyman P Minsky, p 22

[2] Ibid, pp 25–26