Are lower oil prices good news? Not really, if it means the world is sinking into recession.

We know from recent past experience and from common sense that higher oil prices are a drag oil importing economies, since if more $$$ are spent on the same amount of oil, there is less to spend on discretionary goods and services. In addition, oil money sent to oil exporting countries is likely to be spent within those economies, rather than being reinvested in the oil importing company that the funds came from.

Figure 1. A rough calculation of revenue (in 2011$) associated with oil imports and exports, based on 2012 BP Statistical Review data, for three areas of the world: the Former Soviet Union (FSU), the sum of EU-27, United States, and Japan, and the Remainder of the World.

A rough calculation based on 2012 BP Statistical Review data indicates that the combination of the EU-27, the United States, and Japan spent a little over trillion dollars in oil imports in 2011–roughly the same amount as in 2008. Governments have been running up huge deficits and have been keeping interest rates very low to cover up this damage, but it is hard to make this strategy work. The deficit soon becomes unmanageable, as the PIIGS (Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, and Spain) countries in Europe have recently been recently been discovering. The US government is facing automatic spending cuts, as of January 2, 2013, because of its continuing deficits.

Furthermore, lower interest rates aren’t entirely beneficial. With low interest rates, pension funds need much larger employer contributions, if they are to make good on their promises. Retirees who depend on interest income to supplement their Social Security checks find themselves with less income. The lower interest rates don’t necessarily have a huge stimulatory impact on the economy, either, if buyers don’t have sufficient discretionary income to buy the additional services that new investment might provide.

Below the fold, we will discuss what is really happening with oil prices, and consider reasons why lower oil prices may be a signal that the world is again headed for deep recession.

Oil Supply is Not Rising Enough

The big issue is that oil supply is not rising enough–and hasn’t been for a long time.

Figure 2. Actual and fitted oil consumption, based on BP 2012 Statistical Review. Fitted trend value of 2.0% is based on 1983 to 1989 actual data; fitted trend value of 1.6% is based on 1993 to 2005 actual data.

When oil supply doesn’t rise fast enough, there are two opposite effects that can take place:

Figure 3. West Texas Intermediate (WTI) and Brent oil prices, in US dollars, based on weekly average spot prices from the US Energy Information Administration.

(1) The most common effect is that prices will go higher. This can be seen in the upward trend in prices in the last eight years.

(2) The other effect is that prices can drop quite sharply, as they did in late 2008. This happens when parts of the world are entering recession, and their demand is decreasing.

It seems to me that this second effect may be happening this time around, as well. The down-leg we are seeing in the prices may have farther to go, as the recession plays out.

One Problem Area: PIIGS Oil Consumption is Declining

If we look at three-year average growth rates for the PIIGS, we find that there is a close correlation between oil growth, energy growth, and GDP growth. Furthermore, in recent years, a growth (or drop) in energy use seems to proceed a growth (or drop) in GDP. Not all of this energy is oil, but for the PIIGS countries, even natural gas is a relatively high-priced import. Recently, oil consumption has been declining sharply, which could imply further economic contraction.

Figure 4. A comparison of average three-year growth rates on three bases: GDP, oil consumption, and total energy consumption. GDP from USDA Research Real GDP database; oil and energy consumption from BP’s 2012 Statistical Review.

Furthermore, data from the Joint Organizations Data Initiative (JODI) shows that recent PIIGS oil demand is down even more. Comparing oil demand for February-April 2012 with February-April 2011, demand is down by 10% for the five PIIGS countries combined. This would suggest that these countries are sliding more deeply into recession.

US Oil Consumption Is Also Shrinking

US oil consumption is also shrinking.

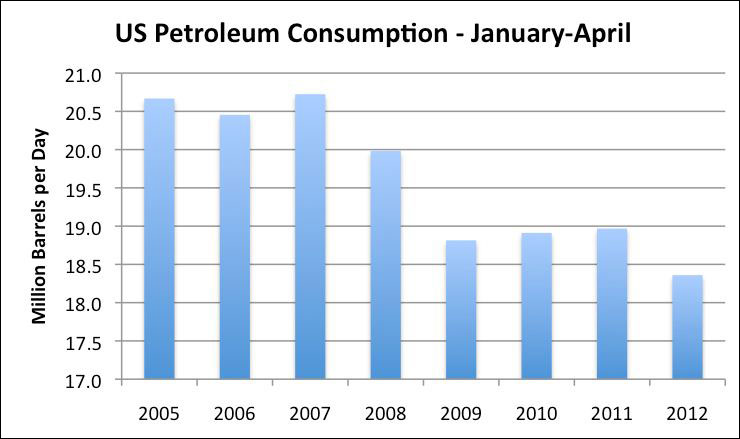

Figure 5. US average consumption of petroleum products, during the months January to April, based on data of the US Energy Information Administration.

US oil consumption shrank by 3.2%, comparing the first four months of 2012 with a similar period of 2011. This is concerning, because based on Figure 5, it looks much like a repeat of the pattern that took place in the 2005 to 2009 time period. Oil consumption was stable during the period 2005 through 2007, then dropped in early 2008 by an amount not too different from the decrease in oil consumption from 2011 to 2012. The bigger step-down in oil consumption came in 2009, after oil prices dropped, and the follow-on effects (reduced credit availability, layoffs) had started. Now oil consumption has been relatively stable in 2009 to 2011, but there has been a step down in consumption in 2012, similar to the step-down in early 2008.

If Oil Prices Stay Down, or Drop Further, Not All Oil is Economic

Oil prices make a difference in a company’s willingness to drill new wells. For example, oil sands production in Canada is quoted as being not economic below barrel, and the West Texas Intermediate price is below that level today. In most instances, existing production will be continued, but new production will be stopped. There are quite a few other types of oil extraction elsewhere (for example, arctic extraction, new very small fields, very deep oil wells, steam extraction outside Canada) that may not be economic at lower prices.

Saudi Arabia makes frequent statements about offering its production to keep prices down, but if a person looks at production patterns in the past few years, they have been highest when oil prices have been highest. Production has dropped as oil prices drop. So a rational person might conclude that oil wells which cannot be operated continuously (of which there are some in Saudi Arabia) tend to be operated when prices are highest, and turned off when prices are lower, thus maximizing profits. As oil prices drop this time around, we can expect Saudi Arabia and others to find excuses to save production until prices are higher.

Countries exporting oil depend on the revenue from the sale of oil, plus taxes on this revenue, to help support country budgets. As oil prices drop, governments find themselves with less money to fund promised public welfare programs. This dynamic can cause lower oil prices to lead to political instability in some oil exporting nations.

Thus, any drop in oil prices tends to be self-correcting, but not until oil production drops, prices of other commodities drop, and many workers have been laid off from work. We saw in 2008-2009 that this kind of recession can be very disruptive.

What’s Ahead?

We can’t know for certain, but the big issue is chain reactions, as one problem causes other problems around the globe. We are dealing with an interconnected international economy. If countries are in financial difficulty, their banks are likely to be downgraded as well. Other banks hold debt of the bank, or of the country in difficulty, or derivates relating to a possible default of the country or bank. If default occurs, these other banks may be affected as well. Thus one default may start a chain of defaults.

Banks that are facing difficulty (inadequate capital, poor ratings), are likely to become more selective in their lending. This makes it even more difficult for small businesses to obtain loans, and may lead to layoffs.

A country which appears to be near default is likely to face higher interest rates, making its cost of borrowing higher. The higher interest costs, by themselves, push the country closer to default.

One of the issues with high oil prices is that the higher prices, especially among oil importers, give rise to a kind of systemic risk that affects many kinds of businesses simultaneously. High oil prices tend to do several things at once: lower the real growth rate, make it more difficult to repay loans, and increase the unemployment rate. All of these issues make it more difficult for governments to function, because governments play a back up role. If workers are laid off from work, governments are expected to compensate laid-off workers at the same time they are collecting less in taxes and bailing out distressed banks. This type of systemic risk leads to the possibility of multiple government failures.

Promises of Future Oil Capacity Growth Aren’t Very Helpful

We keep reading articles claiming that world oil production will grow by some large amount by some future date. One of the latest of these is by Harvard Kennedy School researcher (and former oil company executive) Leonardo Maugeri, called Oil: The Next Revolution. According to the report, “Oil production capacity is surging in the United States and several other countries at such a fast pace that global oil output capacity is likely to grow by nearly 20 percent by 2020, which could prompt a plunge or even a collapse in oil prices”.

Even if the forecast were true (which I am doubtful), the problem is that this is simply too late. We have been having oil supply problems for quite some time–since the 1970s. The rate of oil supply growth keeps ratcheting downward, and the world keeps trying to adapt, with recessions to show for its efforts. (James Hamilton has shown that 10 out of 11 recent recessions were associated with oil price spikes.)

We don’t have time to wait until 2020 to see whether the supposed additional capacity (and production) will actually materialize. We have a problem right now. The downturn in oil prices and the reduction in demand in the US and PIIGS is looking more and more like the current oil price spike (of 2011 and early 2012) may give rise to yet another recession. Based on our experience in 2008-2009, and our difficulties since then, this recession may be severe.

Source: Our Finite World