- Your Not So Bearish but Definitely Concerned Analyst

- A Quick Trip Around the World

- The Beginning of the Endgame

- The Attack of the Zombie Banks

- The Unmentionable Problem of Europe

- The New Religion of Europe

- Will All Europeans Become Germans?

"Come, Watson, come! The game is afoot. Not a word! Into your clothes and come!" – Sherlock Holmes

About this time two years ago I began to seriously work with Jonathan Tepper on our book Endgame: The End of the Debt Supercycle and How It Changed Everything. It came out the following March. I remember vividly that in November of that year, as crisis after crisis hit Europe, and the first of about 20 summit meetings which were supposed to solve the crisis was convened, that Jonathan and I worried that the book would not be out in time to actually catch the Endgame before it happened (at least in Europe).

Ah, such naiveté from your humble analysts. While we predicted (in general) pretty much everything that has happened so far, from Greece to Spain to Italy, the problems with "austerity" in times of crisis, the even larger eventual problems of postponing the day of reckoning, etc., we now must stand back and shake our heads in awe and wonder at the ability of European leaders to kick the can down the road. Given the serious nature of the problems, it is amazing (to us at least) that they have been able to keep the wheels from coming off. In the face of the powerful centrifugal forces that should have torn Europe apart, we must pause and give serious thought to why they have not done so already.

(In the book, we also discussed at length the problems in Japan and the US and looked at several other problematical countries, but we were not worried that those events would preempt our publishing deadline. Those problems are still in our future, but coming at us ever faster as times gallops on.)

For the last year I have been writing that it is not clear that Europe (with the probable exception of Greece) will in fact break up. The forces that would see a strong fiscal union are quite powerful. In today's letter, I will try to bring you up to date on some insights I have had in the 18 months since we did the final book edits.

Your Not So Bearish but Definitely Concerned Analyst

I want to start with a simple observation. I am described by most of my readers and certainly most of the press as "bearish." I am not. I am actually quite the optimist. I have a very positive outlook on the rise of the human condition and the accelerating pace of technology, and believe we are at the brink of an unimaginable era of abundance. My personal investment portfolio is weighted far too heavily on the venture capital end for someone of my (ahem) age. (I would be aghast if anyone I was consulting with had a portfolio that looked like mine!) My personal business is nothing if not based on an optimistic view of the world.

Yes, I have long made the case that we are in a secular bear market in the US (and much of the developed world). But that simply means that I think equities in general offer little upside potential at today's valuations. These periods run in very long cycles and to ignore them is simply, well, dumb. So we look for opportunities elsewhere than in index investing. What makes it particularly challenging today is that central banks are pushing interest rates down and forcing investors to work far harder for their returns. Simple bond investing will not give us the returns that most of us need for our retirement and desired lifestyles.

I prefer to think of myself as an optimistic realist. Rather than trying to force or vainly hoping for a return that is not there, I choose to look elsewhere. There are always opportunities somewhere. In preference to index investing, I look for specific targets. You might say that I prefer a rifle to a shotgun.

Of course, if your worldview is consumed by US equities, if you live and die by every move of the market, then I might seem like a bear to you. I would suggest that if that is the case, you might want to broaden your investment horizons.

What I am bearish on, however, is governments gone wild with ever-increasing taxes and spending, and especially governments that take on too much debt. When governments decide to spend today more than they can collect in taxes; when they borrow ever-greater amounts to live a national lifestyle that is beyond their means, obliging our children to pay in the future for our spending today to maintain that lifestyle; we know that there will eventually be a day of reckoning.

That day comes when the debt is growing faster than the economy. The final Bang! moment happens when the total interest on the debt overwhelms the nominal growth of the economy.

When that happens, whether to a family, a company, or a nation, either spending must be slashed or taxes raised (which will hurt overall growth), or there will be a default. There comes a moment when investors start to worry more about the return of their capital than the return on their capital. Rates begin to creep upward and the process turns into an ever-tightening spiral of rising taxes and falling spending (which we currently call austerity), which hampers the growth of the nation and makes it ever more difficult to escape the debt trap.

In the course of human experience we have watched this process unfold literally hundreds of times, yet we never seem to learn. Somehow, we always manage to tell ourselves that this time is different. Someone else can pay more taxes. We can grow our way out of the problem, just like we did the last time. Or we settle for the desperate, cynical belief that future generations will sacrifice their lifestyles so that we can get paid our unfunded pensions and health care.

Sidebar: my friend Mike Shedlock chronicled this week a rather sobering set of statistics. The US now has more people on government pensions than workers in the private workforce.

- As of 2012-06 there were 111,145,000 in the private workforce.

- As of 2012-06 there were 56,174,538 collecting some form of Social Security or disability benefit.

- The ratio of SS beneficiaries to private employees just passed the 50% mark (50.54%).

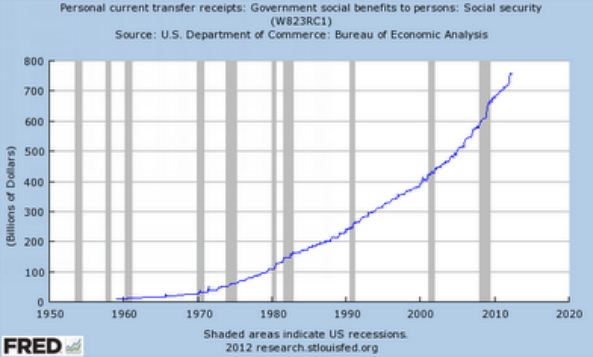

This next chart, from the St. Louis Fed, shows us that the problem is rapidly growing. The accelerating growth in recent years is just going to increase, because the Baby Boom generation is just starting to retire (sadly, I am now eligible for Social Security, if I want to "retire" early). Keep in mind, this is just Social Security; healthcare is far worse.

The same story can be told in many countries throughout the developed world. The US is in worse shape than Europe as a whole, though many countries in Europe are in much worse shape. And forget about Japan. But back to our original topic.

I am bearish on much of the developed world, because the majority of "developed-nation" governments have simply gone too far in debt creation. By "gone too far" I mean that the debt is now too large for them to grow their way out of it. Dealing with the debt is, at best, going to hurt growth and at worst will result in depressions.

A Quick Trip Around the World

Let's take a quick turn around the world. The eurozone part of Europe is well on its way to becoming an economic basket case. Much of the continent is on its way to a true (deflationary) depression. The United Kingdom is going to be growth-challenged at best for the rest of the decade; but given its control of its monetary system, it can try to slowly inflate its way out while allowing nominal growth in the economy and reining in spending. The process will not be without its difficult moments.

Scandinavia is by and large going to be OK, as their economies have either already dealt with the debt crisis (Sweden) or are in control of their own monetary destinies. That being said, Finland will be an interesting study. It is on solid financial ground and has a very low fiscal deficit (it has often run surpluses). The euro could be seen as an unwanted anchor by many Finns, especially if eurozone membership requires substantial taxes and guarantees from the government. Finns have made very clear their objection to bailouts, and it will be interesting to watch how this small and fairly conservative (in terms of budgets) nation deals with its less fastidious southern partners.

Canada dealt with its debt crisis in the early '90s. A quite-liberal government was elected on a fairly far-left platform and then proceeded to forget most of the platform in the midst of the crisis, and did what had to be done to get the budget deficit and debt back under control. And it worked quite well.

We wrote about Australia in a full chapter of Endgame. Their economy never really suffered in the recent debt crisis, in large part due to their growing housing market and their trade with China. If you talk to the average Aussie, they think that all is right with the world. They acknowledge a few issues but see nothing major like the rest of the world has experienced. Jonathan and I think otherwise. Their housing market is by recent standards in a clear bubble (which I know will get me a lot of email). Their banking system is dominated by foreign deposits (shades of Northern Rock, but not as bad as Iceland). They are vulnerable to a Chinese economic slowdown. I should note that Chinese GDP growth was "down" to 7.6% last quarter. That China might slow down should not come as a surprise. No country can grow at 10% forever. Eventually the laws of large numbers and compounding take over. All that being said, Australian government debt and deficits are unde r control. Any problems should be of the nature of "normal" business-cycle recessions and accompanying issues.

My views on Japan are well-known. For new readers, I am given to referring to Japan as a bug in search of a windshield. They can run such huge deficits and sustain the highest debt-to-GDP on record because they have taken their vast savings of the last 50 years to fund the government debt. But the country is aging and the savings rate will soon go negative. Couple that with recent trade deficits and the outlook is grim. They can either raise taxes and cut spending to close their 10% deficits, or print money. Or both. We can see from history how that turns out. Japan will be no different. There is no new math that will somehow enable them to avoid the fundamental consequences of too much debt. I think the yen is a massive short.

The US will have an election this fall, in part to determine how we deal with our own debt issues. If we get the deficit under control (on what I call a glide path to a balanced budget), and couple that with tax reform (see, I really am an optimist), we can avoid becoming eurozone Europe. That implies a much lower growth rate for much of the rest of the decade, for reasons I have written about at length (and that we cover in the book); but we should be able to avoid hitting the wall. If however we avoid the issue, we will turn into Spain faster than you can say spit. It will not be pretty. Ours will be a different type of depression than Europe's, but a depression nonetheless.

The rest of the developing world will have to adjust to that reality. The large engines of growth in the developed world are either going into reverse or sputtering along at lower speeds. I am not suggesting that trade will stop, but it will slow. All in all, we face a most challenging environment.

So with that backdrop, let's take a brief look at some new insights on Europe that have come about since the final edits of the book.

The Beginning of the Endgame

While the problems in the US, Japan, the United Kingdom, and Europe all stem from too much sovereign (government) debt, there are very real differences in how the Endgame plays out.

Europe has the basic problem of a being a monetary union without fiscal union. By that we mean that the eurozone nations have decided to use the same currency and central bank but have very different economies. Some countries need economic stimulus and the ability to lower the value of their currency (because of the relative value of their labor), and different countries have different inflation rates. One central bank size does not fit all.

There are three basic problems. All three must be dealt with or there can be no balanced outcome.

First, there is too much sovereign debt in the peripheral countries of Greece, Spain, Italy and Portugal. Ireland had a monster banking crisis (due to its housing bubble) and was forced to bail out its banks, and thus acquired too much debt.

Spain had a huge housing bubble that at its peak generated 17% of its economy in housing construction and real estate-related activities. Given the total collapse in that sector, is it any wonder that unemployment is 23%? This has wreaked havoc on the national budget, causing very large deficits. Plus, the Spanish banking system has been completely bankrupt for some time. We pointed all of this out in our book. And were told that we simply did not understand the problems of Spain. Some of the Spanish press was not kind. Up until a few months ago, the Spanish government fiercely denied there was any problem in its banking sector at all. Now they have had to ask for a €100-billion bailout.

Sidebar: Many thought German Chancellor Angela Merkel caved in to Italian and Spanish demands for relief. Spanish Prime Minister Rajoy said the money would come with no strings attached. He was mistaken. This week the agreement arrived, with 32 strings attached, some of which require serious austerity measures. Spain is supposed to cut its deficit to the 3% range. It is closer to 9% now. A 6% GDP cut in one year will reduce tax revenues more than forecast, so the deficit will be worse than forecast, therefore requiring more spending cuts and taxes to be raised. Merkel has been shown to be quite adamant in her demands, and her approval rate in Germany has gone up and is now at 66% for her handling of the eurozone crisis. She will not win any approval polls at all in Spain, Italy, or Greece; but those voters don't keep her in office.

Spain is now over the 7% level for its 10-year debt. Its two-year bond is now at 4.5%. Spain cannot even switch to short-term funding to relieve its debt pressure. It will soon lose access to the bond market at any price less than 10%, which is totally unsustainable. While Spain is not Greece, as the causes of its problems are very different, the result is the same. Too much debt means the loss of bond-market access. Spain will soon need a major bailout. And that will come – it MUST come – with defaults on at least a portion of the debt. The default may have another name, like "restructuring"; but bond holders will not get what they thought they were buying. Call it what you will, this will be default. Spain simply cannot service the debt it must take on.

Italy has run up over 120% debt-to-GDP and its 10-year bond is in the 6% range, which is unsustainable at current budget, tax, and spending levels. Six percent is clearly beyond the potential growth rate of Italy. Moody's just downgraded the country to only two notches above junk-bond level and left it with a negative outlook. Sean Egan had downgraded them already.

I have written about the problems of Belgium before. Too few analysts pay attention to Belgium, but there are real problems in the country.

The Attack of the Zombie Banks

The second European problem is that its banks were allowed, if not downright encouraged, to leverage their capital by as much as forty to one with sovereign debt. Banks had to post no reserves for government debt, whether Greek, Spanish or German, as everyone "knew" that developed countries could not default. Except now it turns out they can.

Greece was a European banking nightmare. Spain will be a nightmare on steroids. When Italy starts to have problems, it will look like some B-grade horror movie where zombies keep coming and coming at the poor victims. Slash and hack at them as you will, they just seem to keep popping up around every corner.

The problem with Spanish banks was not too much sovereign debt but too many bad real estate loans. But that has morphed into national economic woes. And what did Spanish banks do with their round of ECB money (the recent LTRO)? They were able to borrow from the ECB at 1% and bought Spanish sovereign debt at 4-6%. Which is the only way that Spain was able to fund its recent bond offerings.

A dysfunctional banking sector is a major drag on any nation. And European companies are about twice as dependent as US companies on the banking system. As an aside, I would not be surprised if ECB President Mario Draghi cut the rate at which the ECB takes deposits from banks to zero or even negative interest, to try and force banks to do something with their money. That will be interesting to watch.

The Unmentionable Problem of Europe

And then there is the third problem: the trade imbalances between northern Europe (Germany, et al.) and the south are not being dealt with. Since the creation of the euro, German workers have become significantly more productive than Greek, Spanish, Italian, or Portuguese workers, to varying degrees. But these trade deficits must be addressed if budgets are to be balanced. And that means lower relative wages in the peripheral countries or higher wages in Germany and the rest of the more-productive north.

If, somehow, some magic is found to deal with the sovereign-debt and banking crisis, the trade imbalances will still be there. And the only realistic way to deal with them is for wages to come down in peripheral Europe. And that will not happen overnight. There will be lingering recessions or depressions in those countries as wages are adjusted. All while governments are forced to cut spending.

Normally, such imbalances are dealt with by currency adjustments. A nation like Italy regularly devalued its currency. But now the peripheral nations have no control over the value of their currency (the euro), so it is wages that must be adjusted. And since no one gets elected on a platform that says all workers must take a 20% pay cut, they're in for a long adjustment period.

For the eurozone not to break up and Europe to form a true fiscal unionfor, all three problems must be addressed and solved. There is no halfway measure that will suffice. Or at least there are no examples in history that I can find.

Austerity measures mean slower growth and an increasingly poor economy, until such time as that magical rebalancing has been achieved. And that takes time. But, as we shall see, time is not on the side of European leaders.

The New Religion of Europe

It is not news that Europe has become increasingly less religious. Church attendance is down, and polls show that there are fewer adherents in Europe than ever.

But there is a new religion that has risen almost without notice. And that is the tent meeting, featuring the revival-like fervor of those who wish for a united Europe, not only monetarily but as a true fiscal whole.

This would be the triumph of hope over history. The problems of creating a monetary union without fiscal union were ignored at the founding of the eurozone. The founders explicitly said that it would be for the next generation to deal with fiscal union. They made it as expensive as possible for a nation to withdraw and left no legal means to do so. Breaking apart the eurozone would be a disaster of the first order. Think at least 7 or 8 of the biblical plagues.

Thus, European government leaders and business elites, especially the financial-system elites, are almost religious in their insistence that there can be no outcome but fiscal union. And they include Angela Merkel. She wants fiscal union on her terms, but she is hell-bent on achieving it, even if it means Germany must give up a significant part of its sovereignty and lose control of the eurozone after such a union is achieved. And while Germany will be the largest part of the union, by economic power and the sheer number of voters, they will not be in the majority. They will lose their ability to dictate how the EU is run by withholding their checkbook.

Even Angela Merkel knows that a fiscal union will eventually mean eurobonds and the mutualization of debt. And that means some mechanism must be created to pay for those bonds. Which in turn requires a de facto taxing authority for the EU parliament. Germany will become just one state among many. Important, powerful, but just one state. And subject to eurozone-wide taxes to pay for those eurobonds, no matter how the terms are couched.

Merkel and other European leaders have not really prepared their voters to deal with the coming changes in sovereignty. But the day is going to dawn when the leaders must come clean and tell their populations what they are planning. And for that matter, the rest of us would like to know, too.

And it is not just Germany. How is France going to react? I think a strong fiscal union and giving up significant sovereignty might be a much harder sell to the French than to the Germans.

Will All Europeans Become Germans?

And finally, let's close with this thought. Does Germany really think that in some future nirvana-like fiscal union, the Greeks, Spanish, and Italians are going to pay their taxes like the Germans do? Really? If their respective governments can't collect taxes now, what makes one think that a eurozone fiscal authority will do any better? Or do they think it will become acceptable for Germans to start behaving like Greeks or Italians, when it comes to taxes?

Do you really think that Germans (or the Dutch or Finns or Irish) will pay their taxes and be unconcerned that citizens of other states are not?

That is the question that must be dealt with, and Merkel and the other northern-tier leaders know it. The issue of trust is huge if you are going to enter into a union with willing populations.

There is considerable momentum being built in Italy among those who would like to leave the euro and return to the lira. Berlusconi has spoken such thoughts, as has the Lega Nord, a significant political party in northern Italy. And so have other, smaller parties. There is also supposedly some serious corporate backing for such a movement, as they hanker for the good old days of devaluation and easier competition.

The Finns have their euro-skeptics, as well as the Dutch. Those being asked to write the checks are leery of signing them and leaving the amounts to be filled in later. And that is where the economic rubber meets the road.

Europe is now faced with a choice between Disaster A and Disaster B. Disaster A breaks up the euro. Disaster B keeps the eurozone together. Both are horrifically expensive, just in different ways. If Germany were to leave the euro it would mean an almost immediate appreciation of the new deutschmark – and a serious hit to their export machine, which is 40% of their economy. Half of those exports are to their European partners. If even 5% of their exports were lost, it would mean a deep recession. And that is a very low estimate of what would be lost, from what I have read. Merkel and other German leaders know the huge price Germany will pay if they leave the eurozone. And the same goes for the other northern countries.

But staying in the eurozone will also entail huge costs. Germany will be forced to help Spain and Italy. Or allow the ECB to monetize their debts, in some form, for a long time. Which will have a significant impact on the value of the euro and lead to inflation, something the Germans greatly fear. German Finance Minister Schauble now allows that 2% inflation would be OK. Privately, he admits it will be at least 4-5%. IF they can hold it to that once the peripheral nations have started to take the drug of monetized debt that others pay for. That is a very difficult habit to shake.

Let's close with part of a piece from this weekend's Financial Times, which speaks to the angst in Germany. This is no trivial matter. It is not clear, at least to me, whether the eurozone will break up or there will be fiscal union. I think, on balance, that the eurozone should break up, due to the immense problems that must be faced in trying to hold it together.

But these real-world considerations do not take account of the religious fervor of Europhile leaders and elites. They are totally committed to making it work. And maybe they can find a way to convert a majority of European citizens to their European Union religion. To that we must say amen and offer a fervent prayer that, whatever they do, it is orderly and does not spread contagion to the rest of the world.

The Piece from the Financial Times is headlined:

"German economists slug it out over euro future

"The gloves are finally coming off among Germany's normally sober and scrupulously polite community of economists in a bitter battle over the future of the euro.

"Serious lecturers in the higher flights of public finance and monetary economics have been trading accusations of stirring up nationalist fears in a 'bar-room debate', according to one faction, and deliberately falsifying the facts, according to their opponents.

"At the heart of the confrontation is a distinguished and media-savvy professor, head of one of Germany's most renowned economic institutes. His emotive language and stark warnings of vast European debts guaranteed by Germany have provoked angry counter-charges of populism from his fellow academics.

"Hans-Werner Sinn, professor at Munich university and head of the Ifo economics research institute, was a leading signatory on a doom-laden open letter, published by the conservative Frankfurter Allgemeine newspaper last week, denouncing the government's moves towards a 'banking union' in the eurozone.

" 'The taxpayers, pensioners and savers of those European countries that are still [financially] sound' should not be expected to guarantee the bank debts of the rest, they declared. The scheme would not save the euro or the European idea, they insisted, but simply benefit the finance houses of Wall Street and London, plus a few rash German investors.

"More than 200 academics have now signed the letter, its authors say. But it has infuriated Wolfgang Schäuble, finance minister, who denounced the writers as 'irresponsible'. Privately he refers to Prof Sinn – whose name means 'sense' – as Prof Unsinn, or 'Nonsense'.

"It has also stirred up the universities. Some 220 academics have signed a counterblast declaring that a banking union is an essential step in managing the eurozone crisis that 'in no way endorses' the collectivisation of bank liabilities.

"A third missive, published in Handelsblatt, the business newspaper, from such luminaries as Bert Rürup, long-serving former chairman of the government's 'five wise men' – its panel of economic advisers – condemns the 'questionable arguments' and 'national clichés' of the original letter. They accuse its authors of 'stirring up fears and emotions' without providing facts to prove their case.

" 'They are like doctors in the emergency ward who say "switch off the oxygen" without having any other solution to offer', says Peter Bofinger, economics professor at Göttingen university and one the 'five wise men'. He challenges Prof Sinn to say precisely where he wants to go.

" 'If they believe Germany would be better off with the Deutschmark again, that is fair enough. But they set off all these fears and anger without providing any other suggestions.' "

(You can read the rest of the piece here.)