The following is an excerpt of Grant Williams' free weekly newsletter "Things That Make You Go Hmmm..." Click here to subscribe.

“We are the hollow men

We are the stuffed men

Leaning together

Headpiece filled with straw. Alas!

Our dried voices, when

We whisper together

Are quiet and meaningless

As wind in dry grass

Or rats’ feet over broken glass

In our dry cellar

Shape without form, shade without colour,

Paralysed force, gesture without motion;

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

Not with a bang but a whimper.”

– T.S. Eliot, The Hollow Men

“He did not know that a keeper is only a poacher turned outside in, and a poacher a keeper turned inside out.” – Charles Kingsley

The Government Pension Investment Fund, Japan (GPIF) does pretty much exactly what it says on the tin, i.e. it is the pension fund for Japanese public sector employees.

It is also the largest such institution in the world and has assets under management that total a truly staggering ¥108 trillion ($1.5 trillion). To put that sum in perspective, it is roughly the same as the GDP of Canada... or Russia.

The first three quarters of 2011 weren’t so kind to GPIF, unfortunately, and, as at December 31, 2011 (the Japanese fiscal year ends on March 31) their AUM had shrunk by a not insignificant ¥2.87 trillion or 2.54% (to continue the GDP comparison, that is like vaporizing the entire Lithuanian economy in nine months). Not good.

A look at the performance of the various investments held by the GPIF demonstrates just how hard it is to invest in the current environment as they showed losses in domestic stocks (-15%), international stocks (-16%) and international bonds (-4%). Fortunately, the one bright spot in their portfolio happened to be their single largest allocation; domestic bonds, which gained a comparatively whopping 2.5%.

A look at the breakdown of GPIF’s portfolio is highly illustrative:

As you can see, almost 70% of the ¥108 trillion in the GPIF’s coffers is sitting in domestic bonds.

That’s roughly ¥75 trillion or trillion in Japanese bonds which sat quietly on GPIF’s balance sheet.

Historically, GPIF has been one of the largest buyers of Japanese government debt and has done more than its fair share to confound those who have predicted Japan’s day of reckoning; including Kyle Bass who has been waiting an awfully long time for his view on Japan to play out as he expected.

In his letter to investors dated November 2011, Bass wrote:

We believe the debts of the following nations, among others, are not sustainable in the current economic environment: Greece, Italy, Japan, Ireland, Iceland, Japan, Spain, Belgium, Japan, Portugal, France and, have we mentioned Japan?

No mixed messages there.

As can be seen from the names on that list, despite Japan’s stubborn refusal to play ball, Kyle still has a pretty good batting average, but on Thursday, his chances of looking very good indeed increased significantly when one of Japan’s biggest poachers announced that they had turned gamekeeper, or, more accurately, one of Japan’s biggest buyers of government debt had rather troublingly, turned seller:

(Bloomberg): Japan’s public pension fund, the world’s largest, said it has been selling domestic government bonds as the number of people eligible for retirement payments increases.

“Payouts are getting bigger than insurance revenue, so we need to sell Japanese government bonds to raise cash,” said Takahiro Mitani, president of the Government Pension Investment Fund... “To boost returns, we may have to consider investing in new assets beyond conventional ones,” he said in an interview in Tokyo yesterday... The fund needs to raise about 8.87 trillion yen this fiscal year, Mitani said in an interview in April. As part of its effort to diversify assets and generate higher returns, GPIF recently started investing in emerging market stocks.

Japan’s demographic nightmare has always been the bedrock of the case outlining why the country’s massive debt—accumulated over twenty painful years—would eventually cripple it, but the problem with demographics as an investment case is that most people can’t even begin to think that far ahead and will readily assume that, because such events are decades in the future, they will be solved long before they become a real problem.

Let’s take a look at the dynamics (for want of a better word) of Japan’s population.

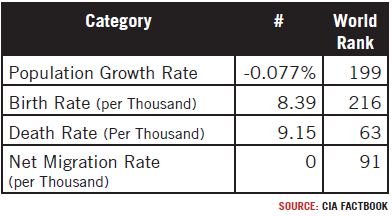

According to official figures published in July 2011, the population of Japan is 127,368,088 (quite an accurate estimate, I think you’ll agree) which makes it the 10th most populous nation on Earth and the table below gives the breakdown of the various components of that number:

So far, so good.

But when we dig a little deeper, Japan’s problems start to bubble to the surface as the numbers in this next table demonstrate:

Japan’s birth rate per thousand places it, interestingly enough, just ahead of Germany, Singapore and Hong Kong, but then the tailenders really kick in with Christmas Island, Niue (who knew?), Tokelau, Pitcairn Islands and Norfolk Island—all amazingly enough sporting a negative birth rate of exactly 9 per 1000—firmly bringing up the rear.

How far down the pecking order does Japan’s birth rate standing of 216th place it? Well the UN officially recognizes 192 countries while the US State Department includes 2 more in its 194.

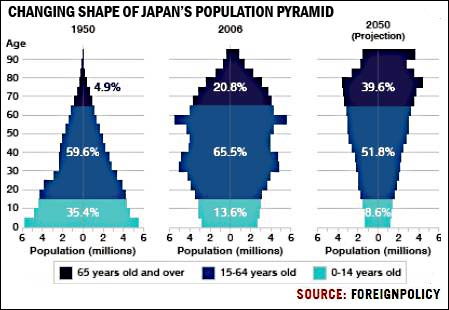

The change in the structure of Japan’s population over the past 50 years is starkly reflected in the country’s population pyramid which looks ever more shaky with each passing year while the forecasts for 2050 are, frankly, frightening (chart, above).

By 2050, Japan’s population is projected to fall to 90m. Incredibly, as recently as 1990, the number of working Japanese was three times that of both children AND the elderly.

In 2011, Japan’s budget for social welfare was ¥90 trillion but that was at least ¥1 trillion short of where it needed to be, precipitating further issuance of government bonds and that, on top of the increased strain caused by the Kansai tsunami has Japan’s bond market teetering on the edge of implosion—still.

A 2011 report from the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research (could that BE any more Japanese?) shed some light on just how fast things could deteriorate from here:

The proportion of children under 15 will shrink from 14.6% of the population in 2000 to 12% in 2021, 11% in 2036 and 10.8% in 2050.

Meanwhile, those of working age (15-64) amounted to 68.1% of the population in 2000, and their proportion is expected to decline to 60% in 2020, 58% in 2035 and 53.6% in 2050.

The only clear rising trend is the aged (65 and above), who will grow from 17.4% of the population in 2000 to 25% in 2014.

The number of elderly will continue to rise while the total population drops so that in 2050 the aged will account for a whopping 35.7% of a population estimated to number only 101 million.

Trouble, folks.