Unsustainable debt. Depression-era fiscal policy. Monetary madness. Welcome to Japan. You may not live or invest in Japan, but your investments may well be affected by what is unfolding in the Land of the Rising Sun. Be prepared.

Japan’s government has vowed to end deflation by pursuing both depression-era fiscal policy and aggressive monetary policy. We recently analyzed implications of Japan’s planned fiscal policies for the yen (see “How Low Will the Yen Go: Depression-Era Policies”). Since then, Bank of Japan’s (BOJ) new governor Haruhiko Kuroda has warned Japan’s debt is not sustainable. Indeed, the only reason why Japan’s debt has been sustainable may be because deficits have historically been financed domestically. However, Japan’s current account balance has been deteriorating: in our assessment, dynamics will be radically different once foreigners are expected to help finance the budget deficit. Already we can see that the yen no longer fulfills the role as a safe haven; that is, whereas the yen was a great beneficiary of the “flight to safety” in 2008, the currency’s status has been eroding in tandem with the country’s current account balance (for more on the yen as a safe haven, see our analysis “Is the Yen Doomed?”)

As domestic investors may not be able to support the country’s deficit any further, and international investors may be unwilling to, the BOJ could step in and buy bonds to help finance the deficit. The valve then, in our assessment, has to be the currency. As the debt is monetized, there could be grave consequences for the yen.

While the yen has weakened of late, we may not have seen anything yet. That’s because unlike the BOJ’s reputation, the central bank there has actually been rather modest in its “quantitative easing” programs in recent years. Here is a chart comparing the amount of money select central banks have been “printing” (the colloquial term for monetary easing, even if no banknotes are physically printed):

Even the open-ended asset purchase program recently announced by the outgoing BOJ governor is modest in comparison to the program of the Federal Reserve (Fed). The BOJ’s program to buy more than trillion1 a year worth of assets is stated on a gross basis, rather than a net basis. Removing reinvestment of maturing securities from the gross amount announced, the net purchases end up being relatively tame2. At the Fed, in contrast, assets are currently being bought at a net rate of approximately trillion a year, reinvestment of maturing securities is left out of the stated size of the program.

That’s the past. There’s a new leadership at the BOJ; a new governor and two deputies have been installed by Prime Minister Abe’s government. The first meeting of the new team is Wednesday and Thursday this week. BOJ’s new governor Haruhiko Kuroda has made it clear he wants Japan to have 2% inflation within two years. One of his deputies has since come out and suggested that this goal might be over-ambitious. But monetary policy is as much about perception as it is about reality: if the market believes a 2% inflation target is achievable, if consumers believe 2% inflation might come, it might become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Trouble is, we do not see how it is possible for the government to finance the debt and ongoing deficits should government bond yields reflect a 2% inflation premium. And because the government might not be able to finance the debt and deficits, the BOJ may step in to do so, very much accepting, possibly even fostering, the negative feedback loop that might ensue for the yen.

With a greater unity within the top leadership and strong support from the Japanese government, there is not much to hold the new BOJ back from unleashing its printing press. To put into context the rather dramatic overhaul at the top of the Bank of Japan, consider the profiles of the retired and new leadership:

What does the new governor Kuroda have in his toolbox? He has long been floating three ideas for Japan’s monetary policy: 1) an ambitious inflation target; 2) an explicit time framework to achieve the inflation target; and 3) a focus on buying long-term Japanese government bonds (JGBs) to boost the monetary base.

Unlike the Fed who pays most attention to core inflation that excludes both food and energy, the BOJ’s inflation target is currently focused on a CPI measure that excludes fresh food but includes energy costs. Note that Japan is one of the world’s most energy-import dependent countries. Fuel imports accounted for roughly a third of Japan’s import bills in 2012. With the shutdown of nuclear power plants, the demand for energy imports, especially LNG, will continue to rise, and energy prices will increasingly weigh on import prices. That means, the CPI measure closely watched by the BOJ that contains an energy price portion will be increasingly associated with the yen exchange rate. In other words, by targeting a CPI measure including energy costs that are largely affected by the exchange rate, the BOJ is implicitly targeting the yen. Kuroda has also made it clear that, going forward, he does not intend to target the core inflation that excludes food and energy. Therefore, a weaker yen will naturally be in the BOJ’s interest in achieving its ambitious inflation target.

The yen has depreciated more than 17% versus the U.S. dollar in the past six months ending March 31, 2013; Japanese stocks have rallied, with the Japanese government bond (JGB) market recently joining the party. Yields on long JGB maturities fell to their lowest levels in a decade, in response to Kuroda’s calling for incorporating long-term JGBs in the QE program. Under the current Asset Purchase Program since 2010, the BOJ can only purchase short-term JGBs with a remaining maturity up to 3 years. The central bank also purchases and holds long-term JGBs, but only through regular market operations separated from the Asset Purchase Program. In addition, under the existing plan, the 2014 open-ended QE will be heavily concentrated on Japanese Treasury bills, with an anticipated monthly purchase of 10 trillion yen, compared to 2 trillion yen of JGBs per month.

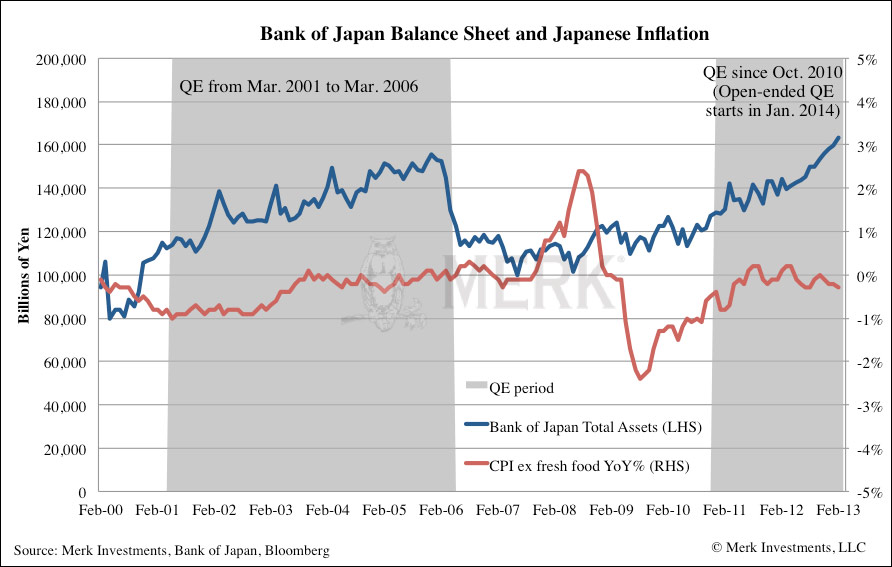

Kuroda’s idea of buying long-term JGBs is not new to the BOJ. The central bank had a half-hearted quantitative easing during 2001-2006, under which it bought long-term Japanese government bonds (JGBs). But it took five years for the BOJ to turn the CPI (excluding fresh food) growth rate positive. Below find the BOJ’s balance sheet size and Japan’s CPI (excluding fresh food) change during two QE periods.

Kuroda does not seem to want to wait for five years. Kuroda’s aim appears to be to achieve the 2% inflation target in two stages: 1% inflation within the first year, and 2% within in the following year. We expect the BOJ under his leadership to aggressively pursue "innovative, non-traditional anti-deflationary policies" that he has advocated for more than a decade, including:

- Pulling forward the open-ended asset purchase program, currently scheduled to start in January 2014

- Beginning outright purchases of longer-dated JGBs in the asset purchase program, or consolidating regular market operations with the asset purchase program

- The purchase of other “risky” (non-government) assets.

- Enhanced attempts to convince the markets through words of the BOJ’s determination to achieve its target

In fact, some of the abovementioned measures had already been discussed in the BOJ’s February 13-14 meeting, when retired governor Shirakawa was still in office. With new leadership in place, we expect the Kuroda-led BOJ to act swiftly.

Some point out that Japanese inflation expectations already picked up, reflected by the higher spreads between nominal yields and yields on inflation protected securities. But this measure is not very reliable in Japan, as Japan hasn't issued inflation-indexed bonds since Oct 2008 and the market lacks liquidity. Having said that, in the monthly households survey conducted by the Japanese Cabinet Office, the share of respondents that expected prices to go higher increased to 70% in February. However, actual consumer inflation measured by CPI ex fresh food year-on-year growth has not made it above zero.

BOJ governor Kuroda will unveil which tools from his toolbox he may deploy. We refer to it as monetary madness because we don’t see how this can have a good ending for Japan, the yen, or the world. Japan has a $6 trillion economy, more than 200 times that of Cyprus. Should the market express its discomfort with Japan’s policies, there will be ripple effects to global markets. For now, the most direct implication is that we are rather negative on the yen. But don’t kid yourself: there may not be a place to hide, there may not be such a thing anymore as a safe asset. We have long argued that investors may want to take a diversified approach to something as mundane as cash. Conversely, there may be opportunities: just as our central bankers have their toolbox, you may want to check the tools deployed in your portfolio.

Co-authored with Yuan Fang

Source: Merk Funds