Originally posted at Briefing.com

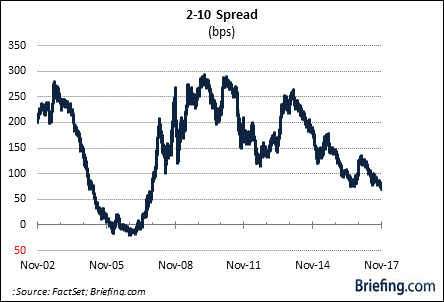

A few weeks ago, we highlighted the apparent contradiction of the reflation trade that has unfolded in the Treasury market. In brief, that contradiction is the flattening yield curve.

This week, we're returning to the yield curve — the 2-10 spread specifically — and we will be discussing what it means if it is indeed a harbinger of slower economic growth.

A Trade of Desperation?

First, we must posit that the narrowing spread between the 2-yr note yield and the 10-yr note yield might not be the telltale economic indicator some pundits think it is.

It could be, yet we can't dismiss the possibility that it's a byproduct of a desperate search for yield among foreign investors staring at such low rates at home.

Hear Russell Napier on Debt Deflation: Too Much Debt, Not Enough Money

Before inflation, the yield on the 10-yr Japanese Government Bond is 0.02%; the yield on the 10-yr German bund is 0.38%, and the yield on the UK's 10-yr gilt is 1.26%. The yield on the 10-yr Treasury note is 2.33%.

Interest-rate differential trades could quite possibly be distorting the yield curve by driving down yields at the back end of the curve at the same time the 2-yr note yield has risen to a nine-year high of 1.64%.

The spread between the 2-yr yield and the 10-yr yield is 69 basis points, which is a 10-year low. A few weeks ago, it was 85 basis points.

The narrowing spread is remarkable in that long-term rates to have dropped while economic growth has picked up and the GOP has embraced a tax reform effort that is being advertised as an expedient for stronger growth.

Something is amiss in that spread relationship. Typically, the spread would widen as growth picks up since stronger growth invites higher inflation expectations that pressure long-term Treasury prices.

That isn't happening here — not yet anyway. Why that remains a debatable point.

Seeing a Peak

David Kostin, the Chief US Equity Strategist at Goldman Sachs, published a note in late October that suggested the US economy might be hitting peak growth. His assertion was linked to the September ISM Manufacturing Index, which hit 60.8, marking its highest level since May 2004.

According to an article that appeared on Yahoo! Finance, Kostin noted that "...an ISM reading above 60 typically marks the peak of growth and presages economic and equity deceleration."

He went on to write that, "Investors buying the S&P 500 at ISM readings of 60 or higher have gone on to suffer negative three- and six-month returns on average as economic activity slowed."

Read Yield Curve Not Suggesting Imminent Market Peak, Recession

Accordingly, we would venture a guess that Mr. Kostin sees the flattening yield curve as an economic indicator more so than the manifestation of an interest-rate differential trade.

What matters more for our purposes here, though, is the tenor of his remarks. He seems to be expecting a growth slowdown, and if that proves to be the case, long-term rates should remain low.

What It All Means

There is a lot wrapped up in the possibility that economic growth disappoints, as some think the flattening yield curve is suggesting it will.

- It means the search for yield will persist, which would provide support for dividend-paying stocks

- It means the administration's contention that tax cuts will be paid for with economic growth will be compromised

- It means the Federal Reserve will be less aggressive with its projected rate-hike path, which would create a buying opportunity at the front end of the curve

- It means growth stocks are apt to retain their preferred investment status vis-a-vis value stocks

- It means earnings growth won't be as strong as expected

- It means commodity demand will be reduced

- It means the labor market will loosen up and wage growth will continue to be lackluster; and

- It means the dollar should weaken

Clearly, there is a lot riding on the yield curve and its propensity to flatten at a time when it should be steepening.

The yield curve is saying something about the future, yet the message is argumentative. The flattening is either a product of interest-rate opportunism or a trade of economic attrition.

The future will settle this argument, yet there is a lot to think about in the present because of the wide-reaching implications of the flattening curve for policymakers and capital markets.