Originally posted at Briefing.com

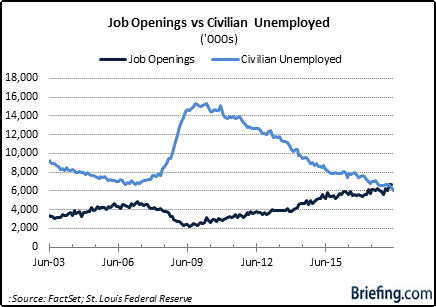

Market participants were literally and figuratively jolted this week when it became known by way of the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) that the number of job openings in April exceeded the total number of civilians officially counted as unemployed.

Specifically, there were 6,698,000 total job openings in April, which exceeded the number of unemployed civilians in both April (6,346,000) and May (6,065,000), as reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics in its Employment Situation Report.

That's a gap that caught everyone's attention for some notable reasons, not the least of which is the understanding that it has never been seen before.

"I Quit"

The JOLTS report, while lagging the Employment Situation Report by a month, was the latest reminder of the vast improvement in labor market conditions.

Other markers include:

- The lowest U-3 unemployment rate (3.75%) since 1969

- The lowest U-6 unemployment rate (7.6%), which counts part-time and underemployed workers, since 2001

- The Hispanic unemployment rate (4.9%) close to a historic low and the African-American unemployment rate (5.9%) at a record low

- The lowest four-week moving average for continuing claims since 1973

Another encouraging sign is that more workers are voluntarily quitting their job. The so-called "quits rate," which is also provided in the JOLTS Report, stood at 2.3% in April.

The quits rate is at its highest level since September 2005 and well above the cyclical low of 1.3% seen in the depths of the Great Recession in April 2009 when the unemployment rate stood at 9.00% before peaking ultimately at 10.0% in October 2009.

To be sure, it was a giant leap to quit one's job voluntarily in 2009, yet the understanding that more workers are doing that very thing today is a reflection of the increased confidence workers have in succeeding on their own or finding work at a different employer.

It is not a stretch to think either that employees voluntarily quitting their job are doing so because they see an opportunity to make more money and/or to have a better work-life balance in a different work arrangement.

It is impossible to have a concrete understanding of why more workers are voluntarily leaving their jobs these days, but make no mistake about it, the increased inclination to do so is what you see in a healthy job market.

Wage Growth Stalls

The missing component in the labor market recovery — and a very important one at that — is a sharper pickup in wage growth. That hasn't been seen, as wage growth has basically stalled the past few years.

There is a deep-seated assumption that wage growth will accelerate soon given the tightening labor market, which should convince employers to pay more to retain existing employees and/or to attract new workers.

The fact that wage growth hasn't accelerated is an oft-cited data point for making the argument that there is more slack in the labor market than one is led to believe by the official unemployment rate.

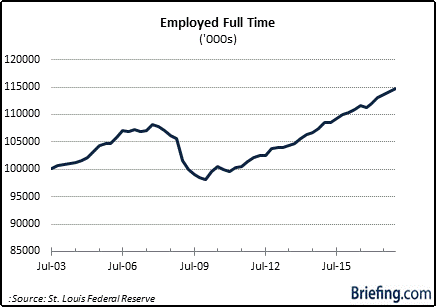

The latter point notwithstanding, there were far more wage and salary workers employed full time at the end of the first quarter than there were just before the start of the Great Recession. It can't be said, then, that there hasn't been a considerable improvement in the labor market, even if one maintains there is more slack in the labor force than today's statistics suggest.

What It All Means

The number of job openings today is the highest since record-keeping began in December 2000. The basis for why there are more job openings than currently unemployed workers is subject to debate.

Three factors we would offer as contributing to the JOLTS gap include: (1) a skills mismatch that is making it difficult for employers to find qualified workers (2) end demand picking up, such that employers need more employees to meet the demand and (3) the pickup in full-time employment has made it more challenging to fill part-time job openings.

Other factors could be at play, yet there is some seeming wage inflation pressure gestating in the three factors we have highlighted.

- If the number of job openings exceeds the number of unemployed due to a skills mismatch, then employers may find themselves in a position of having to pay their existing employees more to do the work or to raise their compensation to attract qualified workers

- If the number of job openings exceeds the number of unemployed due to more openings being created to meet increased demand, employers will need to ensure their compensation is competitive enough to fill those openings, lest they miss out on the added sales opportunities

- If the number of job openings exceeds the number of unemployed due to the pickup in full-time employment making it more challenging to find part-time workers, then the shrinking pool of available workers who would prefer full-time jobs might need to be incentivized more with higher hourly wages to fill part-time positions

The tightening labor market is both a good problem and a potentially bad problem to have.

It's a good problem because it bodes well for the consumer spending outlook — and consumer spending accounts for 70% of GDP. It's a potentially bad problem if wage inflation fuels a pickup in general price inflation that undercuts the bond market, driving up borrowing rates, and forces the Federal Reserve to be more aggressive raising its policy rate.

The Federal Reserve isn't at that point yet. In fact, the Federal Reserve — and every worker out there — would prefer right now to see an acceleration in wage inflation. They might get jolted by that development soon enough if the trends in the JOLTS report persist.