Back in mid-December 2016, the Fed started raising the federal funds rate by 0.25 of a percentage point per quarter. So, the federal funds rate has risen a cumulative 1.50 percentage points since then. When the Fed began these quarterly federal funds hikes back in mid-December 2016, the difference, or spread, between the yield on the Treasury 10-year security and the federal funds rate was 2.13 percentage points. In the week ended August 31, 2018, this spread had narrowed to 0.96 of a percentage point. Thus, since mid-December 2016 through the week ended August 31, 2018, the federal funds rate has risen by 1.50 percentage points as the yield on the Treasury 10-year security has fallen by 0.33 of a percentage point. The yield curve has flattened as a result of the combination of a rise in short-maturity interest rates and a decline in long-maturity interest rates. Unless the economic landscape changes radically in the interim, the Fed is likely to raise the federal funds rate another 0.25 of a percentage point on this coming September 26. If the recent past is prologue, the spread between the Treasury 10-year security and the federal funds rate will narrow further.

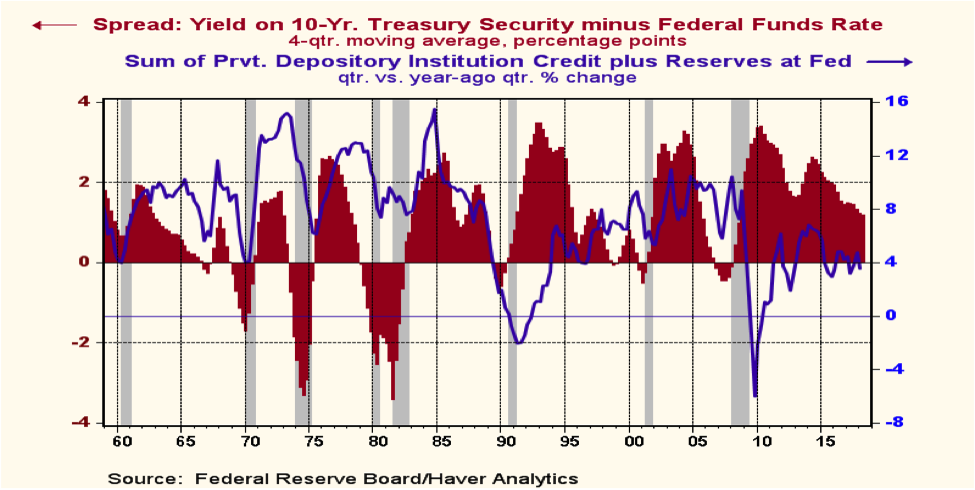

I mention this narrowing in the spread between the yield on the Treasury 10-year security and the federal funds rate, or the flattening in the yield curve because the behavior of the yield curve has the uncanny characteristic of presaging the pace of real domestic demand for goods and services. That is, as the yield curve flattens, growth in real domestic demand slows with a lag. Conversely, as the yield curve steepens (the yield on the Treasury 10-year security rises relative to the federal funds rate), growth in real domestic demand increases with a lag. This leading relationship between the flattening/steepening behavior of the yield curve and the decreasing/increasing growth rate of real domestic purchases is shown in Chart 1 where the red bars represent the observations of the four-quarter moving average of the yield spread in percentage points and the blue line represents the year-over-year percentage changes in quarterly observations of the real gross domestic purchases (real gross domestic product plus imports and minus exports). The vertical shaded areas in the chart represent periods of business-cycle recessions. Notice that the spread between the yield on the Treasury 10-year security and the federal funds rate typically becomes negative prior to the onset of a recession. The exception to this was the recession that commenced in Q2:1960. Although the yield spread narrowed prior to the onset of this recession, it did not turn negative. In late 1966, the yield spread turned negative, but a recession did not occur. Although real gross domestic purchases did not contract, growth did slow precipitously. As I mentioned in a previous commentary, my former colleague at the Chicago Fed, Robert D. Laurent, did seminal research on the leading-indicator characteristic of the behavior of the yield curve. Rest in peace, Bob.

There is a reason to believe that there is causality between the behavior of the yield spread and the behavior of real domestic demand. The federal funds rate is the overnight interest rate on cash reserves traded among depository institutions (banks). The Fed controls the supply of these reserves. To paraphrase the poet Joyce Kilmer, only the Fed can make reserves. Like any other price, the federal funds rate is determined by the interaction of the demand for reserves by banks and the supply of reserves controlled by the Fed. The Fed determines the level of the federal funds rate by altering the supply of reserves relative to the demand for reserves. If the demand for reserves should fall, all else the same, the federal funds rate would also fall. But if the Fed is targeting a particular level of the federal funds rate, the Fed would then reduce the supply of reserves to prevent the federal funds rate from continuing to trade at the lower level. (It is left as an exercise for the reader to explain what the Fed would do if the demand for reserves were to increase such that the federal funds rate were to rise above the Fed’s target level.)

Although the federal funds rate is determined by the Fed, the Fed’s influence on the levels of other interest rates free from credit risk is inversely related to the maturity of the interest-bearing security. The Fed attempts to signal its near-term intentions with regard to the level of the federal funds rate. For example, since its hike in the federal funds rate on June 13, 2018, the Fed has made known its intention to raise the federal funds an additional 0.25 of a percentage point on September 26, 2018. With less certainty, the Fed also has indicated that it will raise the federal funds another 0.25 of a percentage point on December 19, 2018. So, back in mid-June 2018, the yield on six-month maturity Treasury securities reflected expectations of an approximate cumulative increase in the federal funds rate of 0.50 of a percentage point by the end of 2018. But the Fed’s certainty as to how it will move the level of the federal funds rate wanes the farther into the future it peers. Financial market participants implicitly understand the Fed’s uncertainty as to how it intends to move the federal funds rate farther in the future and incorporate this uncertainty in their federal funds rate expectations. Therefore, future Fed intentions with regard to the level of the federal funds rate have minimal influence on the level of the yield on the Treasury 10-year security.

Check out Unless the Fed Changes Course, a 2019 Recession Collision Is the Most Likely Outcome

Suppose the Fed starts raising the federal funds rate. In order to effect (spell check tried to change the “e” to an “a”) the increase in the federal funds rate, the Fed would have to slowdown the rate of increase in bank reserves. Because their marginal cost of funds has increased, banks would raise their loan rates. All else the same, the increase in bank loan rates would cause the quantity of bank credit demanded to slow. But suppose all else is not the same. Suppose that after a series of increases in the federal funds rate, businesses get more pessimistic about the demand for their product. This would induce them to slow down their demand for funds for the purchase of capital equipment. That is, the demand curve for credit would shift back. The fall in the demand for credit would put downward pressure on the structure of interest rates. Although the levels of interest rates on longer-maturity securities would fall, the federal funds rate is prohibited from falling because the Fed is assumed to have not lowered its federal funds target yet. So, a narrower spread between the yield on the Treasury 10-year security and the federal funds rate would result in a slowing in the growth of real domestic demand from a slowing in the quantity demanded of bank credit as a result of the increase in bank loan rates and an outright shift back in the demand for credit in general.

The slowing in the growth of real domestic demand following a narrowing in the yield spread was shown in Chart 1. Chart 2 shows the tendency for the growth in the sum of depository institution credit and depository institution reserves at the Fed, a variant of, you guessed it, thin-air credit, to also slow after the yield spread has narrowed.

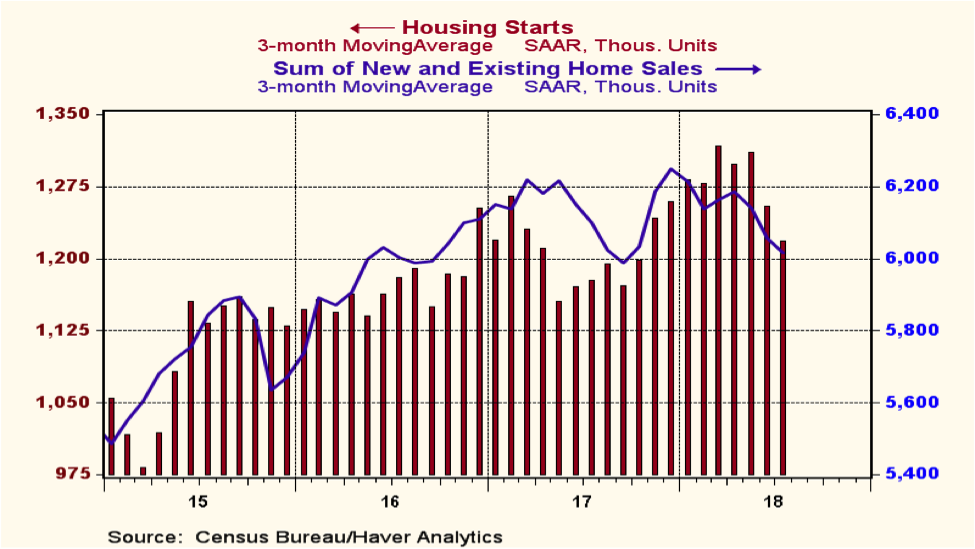

Back to the present. Although the yield curve is flattening, the U.S. economy in the aggregate shows no sign of flagging. But remember, the behavior of the yield curve is a leading indicator. There is one sector of the economy that typically begins to weaken before the aggregate economy does – housing. The data in Chart 3 illustrate that real residential investment (the red line) tends to lead the overall economy (the blue bars) into and out of recession. The data in Chart 4 suggest that currently both home sales and housing starts have begun to weaken.

The stock market also is thought to be a leading indicator. Currently, the U.S. stock market is at or near a cycle and all-time high. This phenomenon is not inconsistent with a flattening yield curve. Although the relationship between the behavior of the yield spread and the behavior of the stock market leaves a lot to be desired, the data in Chart 5 show that a narrowing yield spread tends to lead the decline in the stock market.

Discussions about the flattening yield curve abound of late. As a congenital contrarian, my primal instinct is to say that it is different this time. But from about 45 years of experience, I have come to realize that the phrase “it is different this time” represents the five most dangerous words in an economic forecaster’s lexicon. Perhaps a better guide for an economic forecaster is the translated French expression “the more things change, the more they stay the same”. Bob Laurent and I, mostly Bob, began doing research on the behavior of the yield curve in 1985 when I still was an economist at the Chicago Fed. In August 1986, I took a walk north on LaSalle Street to become an economist at The Northern Trust Company. Bob continued to do research on the yield curve and I continued to believe that he had found the Holy Grail of economic forecasting. The yield spread began to narrow with a vengeance in the second half of 1988, turning negative in Q1:1989 and remaining negative throughout the remainder of the year. As I recall, early in 1989 I started sounding the recession alarm. But the economy remained strong, much as it appears to be currently. Even though the Fed stopped raising the federal funds rate in mid 1989 and started cutting it in the second half of 1989, the yield on the Treasury 10-year security continued to decline and the yield spread remained negative. At the same time that the spread was narrowing and turning negative back then, the Treasury was cutting back on its issuance of longer-maturity securities. With no signs of a weakening economy and thinking that the lack of supply of longer-maturity Treasury securities might be the explanation for the continued decline in the yield on the Treasury 10-year security and the negative yield spread, I concluded that the signal being sent by the behavior of the yield spread was different this time. The recession started around midyear 1990! As I said, the five most dangerous words in an economic forecaster’s lexicon are “it is different this time”.

See Death by Higher Rates? Not so Fast, Says Ralph Acampora

Unless the U.S. economy slows abruptly between now and the end of 2018 and/or unless some external economic or geopolitical crisis erupts that destabilizes financial markets, the Fed is likely to raise the federal funds rate a cumulative 0.50 of a percentage point by yearend. In all likelihood, the spread between the yield on the Treasury 10-year security and the federal funds rate will narrow further from its week-ended August 31 level of 0.96 of a percentage point. Unless it is different this time, the Fed will have set the U.S. economy on a course for, at least, significantly slower real economic growth in 2019 and, at worst, a recession. In addition, the U.S. stock market is likely to perform considerably worse in 2019 than it has in 2018.

One of my former Chicago Fed colleagues, not Bob Laurent, used to joke that it was not too difficult to get paid two times your marginal revenue product, but three times was pushing it. Well, in my case, 3x0, 2x0, 1x0 – the answer is the same. It finally caught up with me. As much as I have enjoyed writing economic commentaries laced with data analysis, I have lost my access to the database of Haver Analytics unless I am willing to work for my marginal revenue product of zero. There are sources of free data, but nothing compares to Haver’s database in terms of user-friendliness, timeliness, and accuracy. So, this will be my final commentary. In the few sentient years I have left, I want to dedicate my time to my wonderful wife of 51 years, my children, my grandchildren, my friends, my community, music and sailing my 51-year old Pearson Commander sailboat on the sparkling waters of Green Bay.

I want to thank all of you that have read my economic rants through the years. I want to especially thank one of my readers and former Northern Trust colleague, Nick Shukas. I first met Nick when he was a back office trade checker with Northern Futures. Back office workers are the unsung heroes of financial institutions. Without them, the show cannot go on. I suppose that just because Nick is an intellectually curious person with broad interests, he started reading the daily comments I wrote for Northern Futures. When Northern Futures closed its doors and Nick transferred to another back office position within Northern, he still read my commentaries. I guess Nick’s a fool for punishment, but he continued to read my commentaries after I retired from Northern and would call me to discuss economic developments. So Nick, thank you and I hope you still call.

Lastly, I am indebted to the management of Legacy Private Trust Company of Neenah, Wisconsin for giving me the opportunity to keep engaging in economic research since my retirement from Northern Trust in the spring of 2012. It has been my privilege to work with the Legacy people whom I hold in the highest esteem for their ethical standards and their trust company expertise. I believe that Legacy’s portfolio management team has a sound and unique approach to investing and I would not hesitate to recommend their services to anyone. Econtrarian out.