Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen made clear two things this week. First, that her and her colleagues are somewhat confounded by the inflation data. And second, that confusion does not yet deter them from their plan for gradual rate hikes. December is still on.

The basic operating framework in Yellen’s speech Tuesday follows that of her speech of September 2015 (where, ironically, she defended the beginning of this tightening cycle that was subsequently put on hold by a slower economy). She decomposes inflation into a function of food and energy prices, inflation expectations, labor market slack, import prices, and “other factors”. Under this decomposition, the “other factors” term this year is unusually large and negative, as illustrated by Yellen’s chart 3.

With this type of framework in hand:

… my colleagues and I currently think that this year’s low inflation is probably temporary, so we continue to anticipate that inflation is likely to stabilize around 2 percent over the next few years.

Hence the conclusion that the Fed should look to the current period of weak inflation to the more optimistic inflation forecast, and use that forecast as the basis for setting policy.

Listen to Interview: Louise Yamada on Stocks, Tech, and Interest Rates

Yellen dedicates the remainder of the speech to discussing the reasons why inflation weakness might prove more persistent:

My colleagues and I may have misjudged the strength of the labor market, the degree to which longer-run inflation expectations are consistent with our inflation objective, or even the fundamental forces driving inflation.

Much of this is not new ground. Indeed, Yellen notes that the Fed has already adjusted policy in light of some of these issues. For instance:

…FOMC participants--like private forecasters--have reduced their estimates of the sustainable unemployment rate appreciably over the past few years… And the direction of potential policy changes is fairly straightforward. If estimates of the sustainable rate of unemployment or inflation expectations fall: Under those conditions, continuing to revise our assessments in response to incoming data would naturally result in a policy path that is somewhat easier than that now anticipated—an appropriate course correction that would reflect our commitment to maximum employment and price stability.

Sounds dovish, correct? And it is – if these factors become more important and the current inflation weakness proves to be more persistent than temporary. But Yellen’s near view term remains hawkish:

How should policy be formulated in the face of such significant uncertainties? In my view, it strengthens the case for a gradual pace of adjustments. Moving too quickly risks overadjusting policy to head off projected developments that may not come to pass… But we should also be wary of moving too gradually. Job gains continue to run well ahead of the longer-run pace we estimate would be sufficient, on average, to provide jobs for new entrants to the labor force. Thus, without further modest increases in the federal funds rate over time, there is a risk that the labor market could eventually become overheated, potentially creating an inflationary problem down the road that might be difficult to overcome without triggering a recession. Persistently easy monetary policy might also eventually lead to increased leverage and other developments, with adverse implications for financial stability. For these reasons, and given that monetary policy affects economic activity and inflation with a substantial lag, it would be imprudent to keep monetary policy on hold until inflation is back to 2 percent.

What’s going on here? Yellen thinks the policy is on the Goldilocks path. Rate hikes are not too fast, not too slow. The inflation weakness justifies the current path rather than a faster pace of increases. But at the same time, uncertainty about inflation should not deter the Fed from sticking to that path. The story is familiar: Employment growth remains in excess of that needed to place downward pressure on unemployment. With the economy already operating near full employment, the odds are high that the economy overheats in the absence of tighter policy.

Indeed, Yellen must believe that, at this juncture, the risks associated with overheating are greater than those of persistently low inflation. This is especially the case given the lags in monetary policy. If they wait until inflation returns to 2% before hiking rates, inflation will almost certainly surpass 2%, at least in her view. To restrain inflation at that point likely requires an acceleration in the pace of rate hikes. And she wants to avoid, at apparently all costs, an acceleration in the pace of rate hikes. Yellen simply has no confidence that the Fed can cool a hot economy without triggering a recession. This is Yellen’s primary motivation for holding the path of policy steady.

There is a secondary reason – the concern that low rate policy will beget financial instability in the form of excessive leverage. The Fed is watching this, but I don’t think it is yet a driving factor in policy decisions. The primary factor remains the possibility of overheating given current low unemployment rates.

Bottom Line: Yellen remains inclined to hike rates in December. It is not clear to me that inflation needs to move up further between now and then to sway her opinion. A solid labor market likely remains sufficient, in her mind, to justify a hike. To the extent this opinion is held more broadly at the Fed, persistent inflation weakness has more implications for the 2018 policy path. Or would, if the Fed was not experiencing so many personnel changes next year; given that we may get five new board members next year, the current guidance might rightly be considered out of date shortly after the beginning of 2018.

Separately, St. Louis Federal Reserve President James Bullard isn’t buying what Yellen is selling. In a speech Wednesday, Bullard concluded that the economy remains stuck in a low growth, low inflation equilibrium and is not poised to exit that equilibrium anytime soon. Notably, he does not anticipate that inflation will return to target in 2018. Moreover, he argues that the impact of lower unemployment on inflation is not meaningful – the Phillips curve is flat as a pancake, so flat that 3% unemployment would support only a 1.7% core inflation rate.

Check out The Investment Clock

Bullard famously owns the bottom dot in the Fed’s Summary of Economic Projections, believing that appropriate monetary policy means no rate hikes through 2020. About as dovish as you can get. Note however that Bullard is arguably screaming into the wind; St. Louis doesn’t rotate back onto the FOMC until 2019.

Boston Federal Reserve President Eric Rosengren placed himself in Yellen’s camp on Wednesday, concluding his speech with:

Temporary fluctuations in prices may obscure the underlying trend for a little while. But monetary policy tends to act with long lags, so it is essential that central bankers do their best to look through the temporary toward the underlying trends. Those trends, as best I can see them at present, suggest to me an economy that risks pushing past what is sustainable, raising the probability of higher asset prices, or inflation well above the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent target. Steps lowering the probability of such an outcome seem advisable – in other words, seem like insurance worth taking out at this time. As a result, it is my view that regular and gradual removal of monetary accommodation seems appropriate.

High asset prices by themselves make him a bit more nervous than other policymakers; most of his colleagues tend to be concerned about the potential for excessive leverage as their financial instability concern.

On Tuesday, Atlanta Federal Reserve President Raphael Bostic gave his first speech since taking that job. I think the speech was fairly conventional; his outlook is largely consistent with those of his colleagues. As far as December is concerned, he falls on the slightly dovish side of the spectrum:

To summarize, I conclude that monetary policy is not currently overly easy. But this is not a statement as to whether or not further adjustments in policy are required. My staff’s own projections indicate continued strength in the economy and progress toward the FOMC’s inflation objective as the year concludes and we move into 2018. I think clear evidence of this path could certainly be consistent with an additional rate hike this year.

Not an overwhelming show of support for December. More supportive would be a “would” rather than “could” in the last sentence. It appears he wants to see some data to justify another rate hike. The December meeting will be a battle between those who want more evidence that inflation is set to bounce next year before hiking versus those who think the forecast is enough. My opinion is that the latter currently has the lead, and further declines in the unemployment rate would cement that lead regardless of the inflation data.

On the data front, new home sales came in on the soft side. Still, this data is fairly volatile month to month and the general upward trend still holds. Not a sharp uptrend, to be sure; the sector remains scarred by the collapse of the housing bubble a decade ago.

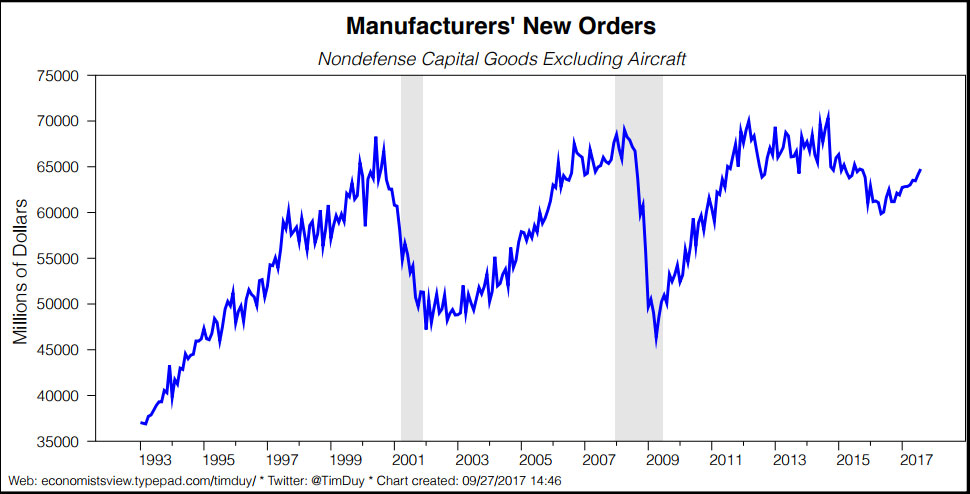

In better news, the new order for manufactured goods came in above expectations. The Fed will be heartened by the continued growth of business investment as it supports their generally optimistic outlook. More generally, the rebound in industrial activity over the past year stands in stark contrast to the downturn in 2015/6 that helped put the Fed on hold and raised recession fears. The Fed will see such data as a reason to stick to its rate hike plans this year.