On August 11th, the hierarchy of the Chinese Politburo surprised the global financial markets, by unilaterally devaluing the yuan against the US$, without any advance notice. Beijing quickly engineered a 3% devaluation of the yuan against the US$ in two days, in what it called a “one-off” operation. Still, the surprise move sent various financial markets around the world into a tizzy as analysts, pundits, and traders began to speculate that the latest move by Beijing was just the first salvo in a campaign to gradually weaken the yuan against the US$, and possibly, to keep the yuan on an even keel with other major reserve currencies, such as the euro and the Japanese yen.

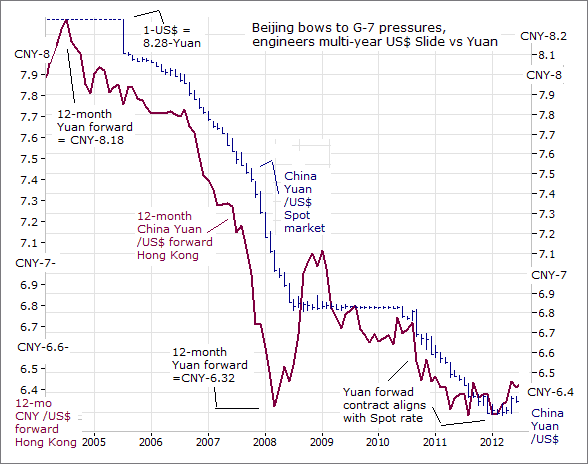

Symbolically, last week’s shock move to devalue the yuan signaled the end of China’s “Strong Yuan” policy that began a decade earlier, on July 21st, 2005. At that time, China’s Politburo had finally bowed to massive pressure from the Group of Seven (G-7) countries—Japan, Germany, France, Italy, Canada, the UK and the US—to un-hinge its currency peg to the US$’s, which had been fixed at a rigid exchange rate at 8.30-yuan, since 1995. After an initial drop of 2.1% on the first day, Beijing engineered a further 16% decline to CNY-6.82 by the middle of 2008. However, Beijing paused the US$’s devaluation for the next two years, and kept the US$ on a tight leash, and until the global economy had emerged from the Great Recession. The US$’s devaluation was allowed to resume in the second half of 2010, until it fell to as low as CNY-6.05 earlier this year.

Beijing adhered to the “Strong Yuan” policy for 10 years, and allowed the yuan to climb by a total of 28% versus the US$. More recently, China’s yuan appreciated by 30% against the Euro, and 65% against Japan’s yen. But now, China is signaling a major shift in regards to the yuan’s exchange rate, under the guise of a more market oriented “flexible yuan” policy. Last week’s sudden devaluation of the yuan was not advertised in advance, and appeared to be a hasty decision. But China’s exports have been contracting for most of this year, and slowing the engine that powers one third of its economy, in large part, because of the yuan’s sharp appreciation against other major foreign currencies, such as the euro, Japan’s yen, Brazil’s real, Russia’s rouble, the Korean won, and US$. China exported slightly more than .3 trillion of goods and services over the past 12 months. The biggest buyers of Chinese goods are the US (17%), EU (16%), Asean (10%), Japan (7%) and Korea (7%).

[Hear: Felix Zulauf on Currency Wars and the Aftermath of the Chinese Devaluation]

The central planners in Beijing have attained an almost mythical status. Year after year, Beijing was able to attain growth of 10% or more over a span of two decades and, in the process, transformed China’s economy into the second biggest in the world, while lifting many households out of poverty and others into the middle class. But the mystique appears to be fading. Beijing is trying to rebalance the Chinese economy, to make growth less focused on exports and more reliant on domestic services and consumer spending. It wants slower but more sustainable growth of around 7%. But engineering such a soft landing is proving more difficult than expected. Most analysts agree that China’s official figures are overstating the growth rate of China’s economy. Commodity traders know this to be the case, given the huge declines in the prices of iron ore, coking coal, copper, natural rubber, and crude oil, which speaks volumes about the sharp downturn in China’s economy.

As fears of a hard landing have increased, China’s policymakers have started to panic. In July, Beijing was forced to quickly arrange radical schemes aimed at preventing a meltdown in the local stock market. China’s newly established “Plunge Protection Team” (PPT), hijacked the stock markets, as the central planners sought to enforce a floor under the Shanghai red-chip market at the 3,500 level. The interventionist measures haven’t restored investor confidence. Professional traders know that China A-Shares traded in Shanghai are trading at a 37% premium above dually listed H-shares in Hong Kong.

Still, Beijing is expected to reduce the value of the yuan gradually, in a carefully orchestrated way, as part of its drive to engineer a soft landing for the economy. And for now at least, the PBoC is expected to intervene in the currency markets in order to control the speed of the devaluation and thereby avoid making the yuan a big issue in the US’s presidential campaign. After the initial 3% devaluation, the onshore spot price in Shanghai followed a pattern of rallies toward the close, sparking speculation the authorities were intervening. But China’s economy has defied the naturally recurring swings in the business cycle, and has avoided a recession for decades, and if China’s economy weakens further, the country’s leadership may not have the luxury of being able to massage its currency incrementally lower. Beijing might have to opt for a faster and steeper decline to boost exporters by slashing interest rates and lowering banks’ reserve requirements.

China’s Economy Is Starting to Buckle Under the “Strong Yuan” Policy

The sudden “one-off” revaluation of China’s yuan caught the world markets completely off guard. However, in hindsight, the pressure that brought about the demise of China’s decade long “strong Yuan” policy, had been developing for quite some time. Most notably, the euro’s multi-year decline against China’s yuan that began in April 2011. China ships about billion per month, on average to the EU, it’s second biggest trading partner, and the yuan’s rapid rise against the euro is taking a heavy toll on Chinese exporters. Most recently, the euro’s slide versus the yuan was greased by the European Central Bank’s (ECB) ultra-easy monetary policy, that ultimately turned to the nuclear option on March 9th of Quantitative Easing (QE-1), with liquidity injections of €60 billion per month.

As such, China’s exports to Europe were 12% lower in July than a year earlier. Exports to Japan, Hong Kong, and Korea, are also contracting at double-digit rates. Output by China’s vast factory sector, which employs tens of millions of workers, is slowing dramatically as demand collapses in its three largest export markets—the European Union (EU), the US, and Japan. With the EU floundering in the swamp of stagnation, caused by austerity, with the US barely growing, and with Japan’s economy sliding back into recession, China’s export growth engine is running in reverse in all three regions. Exports slumped to 5 billion in July, or 8.3% lower than a year earlier. The figures were worse than expected and validated suspicions among private analysts that China’s economy is growing at a far slower rate than the statistics conjured up by government apparatchiks.

On Sunday, August 16th, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) sought to downplay its major shift in currency policy, by saying that further adjustments to the yuan’s value would be much smaller, and likely to move in both directions. The yuan’s initial 3% devaluation versus the US$ on August 11th – 12th, could help to “reduce the possibility of similar sharp adjustments in future,” said Ma Jun, the PBoC’s chief economist. In the future, it is more likely there will be “two way volatility,” or appreciation and depreciation of the yuan. The central bank would move only in “exceptional circumstances to iron out excessive volatility in the exchange rate,” Ma said.

[Read: Do Markets Determine the Value of the RMB?]

However, China’s shift towards a weaker yuan dragged other Emerging currencies, such as Turkey’s Lira, Indonesia’s rupiah, South Africa’s rand, Brazil’s real, and Mexico’s peso, to new historic lows. Also vulnerable to a yuan devaluation are the Thai baht, the Singapore and Taiwan dollars, the Chilean and Colombian pesos, Russia’s rouble and the Peruvian sol. China is the top export destination for most of these countries on Morgan Stanley’s “Troubled-10” list. However, the PBoC’s Ma is quick to add, “China has no intention or need to participate in a currency war. There is no need to worry. The central bank will continue to intervene in the market to support the yuan as necessary. In the future, even if the central bank needed to intervene in the market, it may be in either direction.”

Still, the majority of traders believe that Beijing’s decision to devalue the yuan was a public admission that China’s economy is stumbling badly. The PBoC is expected to inject additional yuan liquidity into the Shanghai money markets in the months ahead, in order to engineer a currency devaluation by as much as -10%. On August 19th, the PBoC injected a net 150-billion yuan (-billion) in open-market operations, and a further 170-billion yuan through loans and an auction of deposits. Further reductions in short-term Chinese interest rates are likely, with China’s consumer price index is running at +1.6%, well below the +4% target set by the PBoC, while producer prices were -5.4% lower in July compared with a year earlier, the slowest since October 2009, - mainly due to slumping commodity prices.

Like many things in China’s economy, the yuan is controlled by a mix of market forces and government decree. Until now, Beijing set a target for the trading of its currency against the US$, then allowed investors to buy and sell the currency within a band - set by the PBoC. However, on August 11th, Beijing made a technical change to give market forces more influence in determining the yuan’s value: it said that “henceforth the mid-point of an expanded 2% band within which the currency can move on any single day would be based on the previous day’s closing value.” In other words, the yuan’s exchange rate would become more volatile, and adds an extra degree of risk, for investors in Chinese based assets. The new policy could also attract a bigger swarm of speculators into the foreign currency markets, especially for currency pairs against the yuan, traded in Hong Kong.

In some ways, the move to a wider trading band, follows what US-politicians have been pushing for China to adopt for more than a decade; a more market-oriented exchange rate. The PBoC said the daily starting rate would be set in line with “demand and supply conditions in foreign exchange markets and the movement of major currencies.” As such, Beijing could begin to enforce a more even playing field, as part of its “free-market reform,” that targets the value of the yuan to the Euro and the Japanese yen, and the currencies of its major trading partners, such as Korea, Taiwan, and Australia.

[Hear Also: Book Interview With Worth Wray on China: A Great Leap Forward?]

China’s yuan is one of the few currencies in the world that has not devalued a lot against the US$ in the past year. Instead, it’s up about 20% against a basket of other currencies that China trades against. Although Beijing has devalued the yuan by 3% against the US$ so far, it’s still far behind the devaluations of other major currencies. Countries that don’t join the currency wars, usually end up suffering as they export less. It’s a very big problem for China, and it’s not going away anytime soon.

The 12 month Chinese yuan forward contract, traded in Hong Kong, which matches traders’ forecasts of where the yuan/US$ exchange rate will be in one year’s time, was trading at CNY-6.27 before the PBoC’s sudden move, or just 1% above the spot rate. As of August 20th, it’s trading at CNY-6.61, or 3% above the yuan’s spot rate in Shanghai. In other words, the entire extent of the yuan’s devaluation against the US$ is projected to be around -6% within a year’s time.

The PBoC says the move was a one-off depreciation, and PBoC deputy Yi Gang said there is no basis for continued depreciation of the yuan. In any event, any effort by the PBoC to weaken the yuan further against the euro would get significant pushback from the ECB, which is injecting €60 billion of fresh liquidity each month through Sept ’16, as part of its bond buying scheme. Since the start of Dec ’14, the ECB has injected a net €500 billion of excess liquidity into the euro zone’s banking system, as part of its effort to weaken the euro’s exchange rate. The ECB’s telegraphing of the launch of QE 1 and its actual implementation was the primary driver that drove the Chinese yuan 30% higher against the euro in the 12 months thru April ’15.

However, the euro has slipped from its recent highs, weakened in large part by the PBoC’s counter moves. The PBoC has slashed reserve-requirement ratios (RRRs), by a total of -150 bps to 18.5% for large banks, thus freeing up an extra 1.8 trillion yuan (0 billion) of liquidity. Combined with four lending rate cuts totaling -150 basis points to 4.85%, the PBoC succeeded in knocking the yuan’s exchange rate lower against the euro, from as high as €0.152 in April to around €0.1395 today.

Yuan’s Slide vs. Euro Knocks German DAX Into Correction Territory

Interestingly enough, the yuan’s gyrations against the euro are having a significant influence over the direction of the blue-chip German multi-national companies (MNCs) listed on the Deutschland Börse in Frankfurt. Germany’s DAX-30 index has slumped by 16% from its all-time high at 12,350 in April, and tumbled to below 10,400 this week, while closely tracking the yuan’s slide to an eight month low against the euro. That means Europe’s top benchmark stock index has descended into correction territory, with little chart support seen until the psychological 10,000 level. A key catalyst behind the DAX’s most recent 1,200-point plunge since July 7th was the Chinese yuan’s 6% decline against the euro.

German exports to China have doubled since 2008 and reached a record €75 billion last year. German companies are also operating affiliates and factories on the ground in China. Volkswagen is a leader in China’s auto market and luxury rival BMW was also on pace for a record year of Chinese car sales, mostly thanks to its Mercedes-Benz unit. German pharmaceutical leaders Bayer AG and Merck KGaA are pouring money into Chinese operations as they battle for global market share with a wave of new investments and acquisitions. Up for grabs is a fast growing 2 billion pharmaceutical market that will soon rank second in the world behind the US. China accounted for roughly 10% of Bayer’s €11.2 billion pharmaceutical sales last year. Bayer is among the top 4 MNCs in the Chinese market.

However, German MNCs, such as Bayer and Merck, Daimler, and Volkswagen operating in China will find their revenues generated in yuan are worth less in euros when repatriated back to headquarters. As such, traders are knocking the share prices of DAX exporters sharply lower. The German Chamber of Commerce estimates that around 5,200 German companies are operating in China in 2015, focusing on high-tech industries and manufacturing, and employing 1.1 million workers. But given the latest devaluation of the Chinese yuan against the euro, the value of these fixed assets are worth less.

Even before the latest move by the PBoC to devalue the yuan, only 27% of German companies operating in China were optimistic about business conditions in the local economy, according to the Business Confidence Survey conducted by the German Chamber of Commerce in China between May 11th and June 12th. The survey highlighted the difficulties in finding and retaining qualified staff as well as increasing labor costs as top business challenges. Other hurdles include currency risks, bureaucratic red tape, slow internet speed, internet censorship, domestic protectionism, unclear regulatory framework and intellectual property theft that worsens the investment climate in China. As such, 30% of German companies are now considering moving their locations outside of China.

Sharp Slowdown in China Knocks Taiwan Dollar to Six Year Low

A key bellwether of the Asian economy and high-tech demand is the 5 billion economy of Taiwan, one of the five “Asian Tigers.” Taiwan has re-tooled its economy towards high-tech over the past two decades and currently has the fourth largest information hardware and semiconductor industries in the world. Taiwan is home to Taiwan Semiconductor <2330.TW>, the world’s largest contract chip maker and Hon Hai Precision Industry <2317.TW>, also known as Foxconn, which is a key supplier of many components for the production of Apple’s <AAPL> iPhones and iPads, produced at its massive plants on mainland China. Taiwan’s high-tech exports account for about 20% of the island’s GDP and, overall, Taiwan’s exports-to-gross domestic product ratio stands at a whopping 70%. Almost half of Taiwan’s exports are of electronics, making it extra-vulnerable to gyrations in external demand.

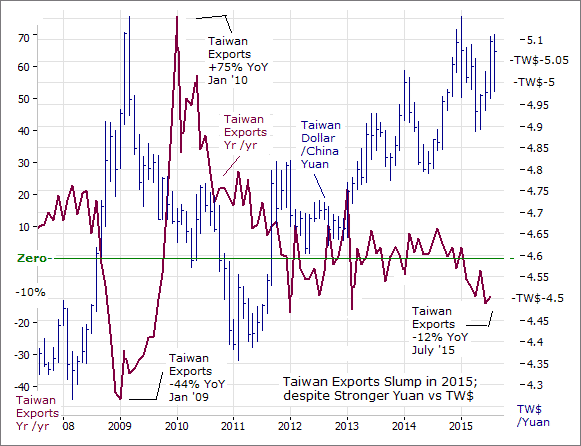

Taiwan is small but it punches above its weight. As a whole, the island exported 4 billion last year, 21st in the world, and only billion shy of India. However, the island’s exports have been shrinking this year, and were 12% lower in July compared with a year ago. Taiwan’s exports, the key engine of its economy, have been mostly flat or contracting for the past 3-½ years. Analysts have warned that Taiwan is quickly losing its edge due to competition coming from just across the Taiwan Strait. China can make most of Taiwan’s export products on its own. From steel and petrochemical to flat panel and semi-conductor, China is establishing its own supply chain to replace Taiwan. Taiwan’s semi-conductor production for instance was 2.6 times bigger than that of China five years ago, but that expected to narrow by half to 1.3 times this year. And Taiwan can’t compete with China in terms of cost or scale.

Taiwan is also losing its attraction to foreign investment, as its trade deal with China has been put on hold. Progress with a preferential trade deal between China and Taiwan has been held up after its service trade pact was stalled in June by the island’s divided parliament. Earlier this week, the Taiwan dollar fell to 30.6 US-cents, a six year low, after the government cut its forecast for annual economic growth by more than half to +1.56%, from +3.28% in May. Exports are now projected to contract for the year, dragged down by a global slowdown and growing competition from Chinese technology firms.

[Interview: Richard Duncan: Markets in Danger as Global Slowdown Continues]

Asian currency traders expect the PBoC will engineer a further devaluation of the yuan over the next six months to make China’s exports more competitive in the world market. China’s economic output accounts for 43% of the Asian Pacific region, so there is no doubt that other regional currencies will follow the yuan to move lower, while the magnitude of the falls in different currencies will vary. In the first seven months of 2015, China and Hong Kong accounted for 39% of Taiwan's total exports, and so the Taiwan dollar won’t escape the impact from the yuan's depreciation. Taiwanese exporters are calling for a weaker TW$, with some suggesting a target of 27.7 US-cents. Most ominously, Taiwan’s exports are tumbling, even though China’s yuan has risen to above TW$-5, which should make Taiwan’s exports more competitively priced compared to its Chinese rivals. Other regional currencies, such as Korea’s won, Japan’s yen, and the Singapore dollar, are expected to face similar downside risks.

Like many other stock markets around the world, the Taiwan stock market was climbing sharply higher over the past few years, in defiance of weakening economic fundamentals. Exports—the key engine of economic growth—have been stagnating or deteriorating for the past 3 ½ years. However, the Taiwan stock market has taken a beating over the past four months. After briefly touching the psychological 10,000 mark in the month of May, the Taiwan stock weighted index has dropped like a rock, plunging 20%, and briefly falling below the 8,000 mark this week, as investors’ confidence was eroded by the stalemate over the preferential trade deal with China, and officials warning that further delays could have a devastating effect on Taiwan’s economic future. Traders were spooked by reports that Taiwan’s GDP for the third quarter is expected to grow only 0.1% from a year earlier, coming closer to zero growth, according to the government’s updated estimate.

The weighted index on the Taiwan Stock Exchange closed at its lowest in two years, due to selling in large-cap stocks, in particular in the financial and electronics sector. Taiwanese suppliers to Apple, such as smartphone camera lens supplier Largan Precision (大立光) were hard hit. Investors do not have high hopes that the launch of the next iPhone models, likely in September, will boost these Apple suppliers' shipments. Within the financial sub-index Fubon Financial Holding (富邦金), Cathay Financial (國泰金), and SinoPac Financial (永豐金) have large exposures to China so a weakening yuan could cost them a lot. Even worse, volatility in the China equity market is expected to hurt them further as they own a large chunk of Chinese securities. However, to arrest the downturn, Taiwan’s Bureau of Labor Funds, which manages labor retirement, pension and insurance funds, is suspected of having bought into Taiwan Semiconductor (台積電), the most heavily weighted stock in the local market, in a bid to put a safety net under the market.

This article is just the Tip of the Iceberg of what’s available in the Global Money Trends newsletter. Global Money Trends filters important news and information into (1) bullet-point, easy to understand reports, (2) featuring “Inter-Market Technical Analysis,” with lots of charts displaying the dynamic inter-relationships between foreign currencies, commodities, interest rates, and the stock markets from a dozen key countries around the world, (3) charts of key economic statistics of foreign countries that move markets.

Subscribers can also listen to bi-weekly Audio Broadcasts, posted Monday and Wednesday evenings, with the latest news and analysis on global markets. To order a subscription to Global Money Trends, click on the hyperlink below:

https://www.sirchartsalot.com/newsletters

or call 561-391- 8008, to order, Sunday thru Friday, 9-am to 9-pm EST

This article may be re-printed on other internet sites for public viewing, with links to:

https://www.sirchartsalot.com/newsletters

Disclaimer: SirChartsAlot.com’s analysis and insights are based upon data gathered by it from various sources believed to be reliable, complete and accurate. However, no guarantee is made by SirChartsAlot.com as to the reliability, completeness and accuracy of the data so analyzed. SirChartsAlot.com is in the business of gathering information, analyzing it and disseminating the analysis for informational and educational purposes only. SirChartsAlot.com attempts to analyze trends, not make recommendations. All statements and expressions are the opinion of SirChartsAlot.com and are not meant to be investment advice or solicitation or recommendation to establish market positions. Our opinions are subject to change without notice. SirChartsAlot.com strongly advises readers to conduct thorough research relevant to decisions and verify facts from various independent sources. Copyright © 2005-2015 SirChartsAlot, Inc. All rights reserved